If I had a nickel for every time a Carboniferous animal tackled by Nigel Marvin in Prehistoric Planet received a detailed description of their head, I’d have two nickels.

Which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice.

On October 9th, a team of paleontologists led by Mickaël Lhéritier of Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 published a description of several new specimens of Arthropleura. Widely accepted to be the largest Arthropod to ever live on Earth, fossils of this titanic Myriapod – the family that includes Millipedes and Centipedes – have been known to paleontologists for over 150 years. While the trackways and hard exoskeletons of Arthropleura have been found across Europe and eastern Canada, the soft and boneless skull had remained undiscovered, leading to uncertainties regarding Arthropleura’s appearance, behaviours, and relation to modern Myriapods.

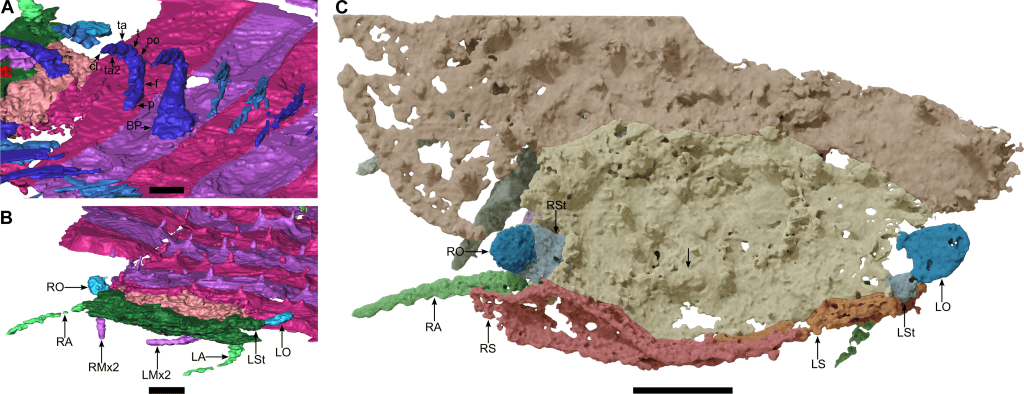

Enter Lhéritier’s study. Using CT-imaging and X-ray technology, Lhéritier’s team examined several specimens of juvenile Arthropleura discovered in the Montceau-les-Mines Lagerstätte of eastern France[i]. What they found was incredible: the heads of not one, but two Arthropleura were preserved. Specimen MNHN.F.SOT002123 contains the entire cranial structure, while only the left portion of MNHN.F.SOT002118’s head remains preserved. The scanned images of MNHN.F.SOT002123 are of particular note, both for their incredible detail and the goofy visage of Arthropleura they have created:

What a face indeed!

The information learned from these specimens is outstanding. We now know that Arthropleura possessed large eye stalks akin to those of crabs, as opposed to previous reconstructions which featured their eyes on their heads. A pair of large antennae emerged from the head’s underside, while a set of massive, centipede-like mandibles protruded from its anterior. Even parts of the feeding apparatus can be observed in the fossils, making them truly one-of-a-kind remains.

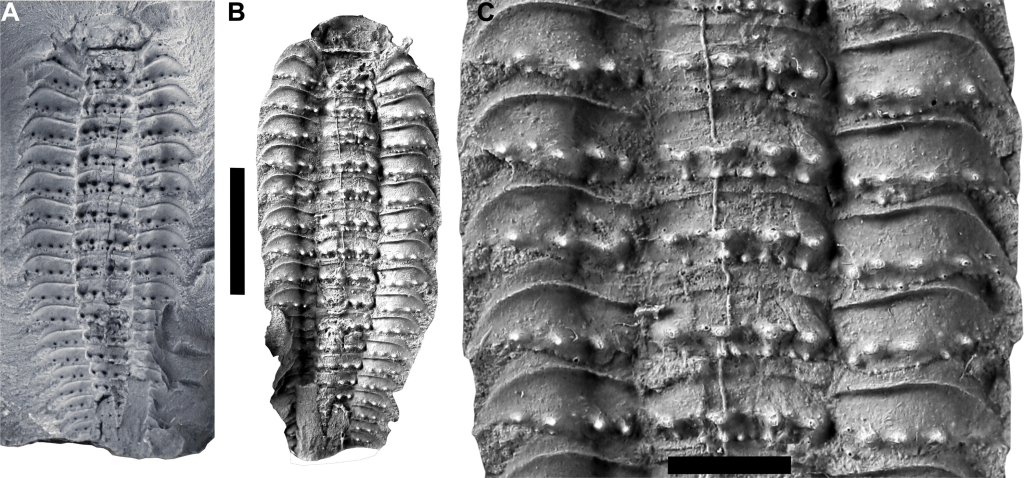

Besides the head, the majority of Arthropleura’s body was also analysed within Lhéritier’s study. The plates that ran throughout its body contained two rows of small lumps known as tubercles on each plate, which could offer extra protection for the immense Arthropod. The number of legs present in MNHNF.F.SOT002123 and MNHN.F.SOT002118 vary, with 44 pairs recognized in the former and 40 in the ladder. While this may seem to be low, it’s important to remember that not every species of Centipede and Millipede has hundreds of legs, making the relatively low leg count of Arthropleura reasonable.

Putting all these characters together, the authors determined that Arthropleura was a stem-Millipede. However, many of its characters show similarities with both Millipedes and Centipedes, namely in the head. The authors believe this could suggest a closer relation between these two lineages, with Arthropleura representing an early offshoot of these iconic arthropod families.

Beyond its evolutionary relationships, the new specimens of Arthropleura have helped to reveal some additional information about this enigmatic animal’s life and growth. First, the mouth apparatus has added support to the notion that Arthropleura was a detritivore, an animal that ate decaying plant matter. This would have been a great choice of diet during the Carboniferous, a period synonymous with the dead plant matter it produced that would later create most of the world’s coal deposits. Second, the number of body segments in the juveniles compared to adult specimens suggest that Arthropleura gained leg and body segments as they grew, eventually topping out at the gigantic 2.63-meter-long adults observed in the genus[ii].

You may wonder about one question: why did these individuals keep their heads while others didn’t? The answer lies in the prehistoric environment of Montceau-les-Mines. During the Carboniferous, Montceau-les-Mines was a diverse ecosystem with marshes, swamps, and rivers dotting the landscape[iii]. Critically, the sediments underlying Montceau’s waters were anoxic, allowing soft tissues to fossilize when they would normally decay. In other words, they were perfect conditions for the bodies of invertebrates like Arthropleura to be preserved in, thus enabling the heads of the juvenile Arthropleura to become fossilized and remain intact for over 300 million years.

In one landmark study, many of the questions surrounding Arthropleura were finally answered. We now have a face for one of the most iconic prehistoric animals to ever walk our earth, a crab-eyed behemoth of a bygone era defined by dead plants and giant insects. If Arthropleura wasn’t already the perfect mascot for the Carboniferous, its newfound visage has certainly made it so.

Happy Spooky Month!

I do not take credit for any images found in this all article. All images come courtesy of the respective artists noted. Header Image courtesy of Ekhyl (@DehautNathan) on twitter.

Works Cited:

[i]Lhéritier, Mickaël, et al. “Head anatomy and phylogenomics show the Carboniferous giant Arthropleura belonged to a millipede-centipede group.” Science Advances, vol. 10, no. 41, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adp6362.

[ii]Davies, Neil S., et al. “The largest arthropod in Earth history: insights from newly discovered Arthropleura remains (Serpukhovian Stainmore Formation, Northumberland, England).” Global Biodiversity Information Facility, 1 Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.15468/bm7amj.

[iii]Perrier, Vincent, and Sylvain Charbonnier. “The Montceau-les-Mines Lagerstätte (Late Carboniferous, France).” Comptes Rendus Palevol, vol. 13, no. 5, Apr. 2014, pp. 353–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2014.03.002.