A century ago, the silent-film adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World debuted in theatres. The first movie to bring dinosaurs and actors together on screen through use of stop-motion animation, The Lost World set the stage for films like King Kong and Jurassic Park, thus making it a crucial entry for both cinematic and paleontological history.

In this 3-part series of articles, the complete history of The Lost World will be covered in excruciating (and, as I have been told, unnecessary) detail. From its inception as a way for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to explore new creative directions beyond Sherlock Holmes, to a review of the film and reflection of its less glamorous elements, and finally how our views of dinosaurs have changed since it’s 1925 debut, I’ll dive into the legacy of one of the earliest works of paleomedia. Below is a table of contents to help guide your navigation of part 1: origins and legacy!

Table of Contents

- Origins: A Tired but Inspired Writer

- The Early Days of Dinosaur Film: A Talented & Revolutionary Sculptor

- Pre-Production: Magicians, Lawsuits, & Leg Injuries

- Release & Legacy

Origins: A Tired but Inspired Writer

The year was 1911, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was looking for a change. During a year that would see Doyle publish 3 new additions to his beloved Sherlock Holmes saga, tales emerging from the beautiful and dangerous world of South and Central America enthralled the British author. The accounts of explorer Percy Harrison Fawcett, in combination with reports of new dinosaurs being discovered both in England and throughout the American Midwest, inspired Doyle’s most ambitious tale yet[i].

First printed in 1912, Doyle’s The Lost World follows larger-than-life professor George Edward Challenger on his quest to prove the survival of extinct creatures hidden in South America. On his perilous journey, Challenger and his companions encounter a myriad of prehistoric animals including the English dinosaurs Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, the newly found American dinosaurs Stegosaurus and Allosaurus, the giant flightless bird Phorusrhacos, pterosaurs, and more[ii]. If you are interested in reading The Lost World, a virtual copy can be read on The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia, linked here.

As you can imagine, Doyle’s tale captivated audiences. At a time when the public’s exposure to both dinosaur research and the Amazon Rainforest was limited, the notion of living dinosaurs roaming the vast unexplored expanses of South America’s foremost jungle fascinated Doyle’s readers. Though not the first ‘lost world’ narrative in fictional storytelling – that honour belongs to works like King Solomon’s Mines by H. Rider Haggard – the success of The Lost World and its novel use of prehistoric creatures helped popularize the trope to extents not previously imagined[iii].

It wasn’t long before an emerging industry took an interest in The Lost World: cinema. By 1912, Doyle’s work had proven pliable to the burgeoning industry, as Sherlock Holmes had already been developed into a 30-second silent film entitled “Sherlock Holmes Baffled” with another Holmes film released in 1916. Clearly, Doyle’s storytelling could translate to the big screen, but one question loomed large: how on earth could they depict the dinosaurs?

The Early Days of Dinosaur Film: A Talented & Revolutionary Sculptor

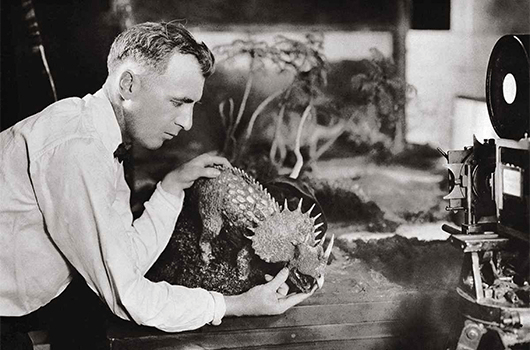

Enter Willis H. O’Brien. A man of all trades, O’Brien had first been exposed to dinosaurs while working as a guide in Oregon, helping to aid paleontologists in their search for ancient life[iv]. After becoming an architect draftsman for the San Francisco Daily News, O’Brien began tinkering with sculptures in his spare time, with two of his crafts – a dinosaur and a caveman – being displayed at the 1915 San Francisco World Fair[v]. Though it is unknown what dinosaur O’Brien showcased (if you have the information, please let me know!), they clearly impressed, as one attendee commissioned O’Brien to create a film using his models.

The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy is, technically speaking, the first dinosaur film. A 6-minute short released in 1915, O’Brien’s work is a strange compilation that blends a caveman trying to impress a girl with a gorilla-like “missing link,” a tall flightless bird, and a large sauropod in the vein of Diplodocus or Brontosaurus. The film is a relic of the past, shall we say. I think Riley Black said it best when they dubbed it “a strange bit of cinema,” a statement that I couldn’t agree more with[vi]. It can be found at this link.

To bring his dinosaurs to life, O’Brien utilized a method of filmmaking called stop motion. In this method, the filmmaker alters the posture and poses of sculptures at a minute level in quick succession, with photographs being taken following each manipulation. When the photographs are cycled through, it appears as though the sculpture is moving naturally. Modern examples of stop motion include works like Wallace and Gromit (1989-present), Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), Coraline (2014), and the Robot Chicken television series (2005-present).

Viewers were enthralled. One of these viewers was none other than Thomas Edison, the American tycoon and owner of the world’s first film studio. Upon seeing O’Brien’s work, Edison commissioned two more prehistoric films: Prehistoric Poultry (1917), a story about a caveman hunting a Moa bird; and R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. (1917), which saw its caveman protagonist use a sauropod as a plow. O’Brien did reuse some of his models from The Dinosaur and the Missing Link in his following productions, but it wouldn’t be much longer until he elevated his game.

In 1917, O’Brien undertook his most challenging work yet: The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. Released in 1918, the 19-minute film follows the journey of Jack Holmes and his nephews around Slumber Mountain, where a magic device allows Jack to glimpse back in time. Like his previous works, Brontosaurus makes an appearance, though the inclusion of two Triceratops battling each other and a subsequent Tyrannosaurus rex attack was far more daring than his previous work. Little did O’Brien know his battle between T. rex and Triceratops would be the first of many depicted conflicts between these two titans of the Cretaceous on film, setting up a legacy that lasts to the present day. To watch The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, follow the link here.

Setting the stage for decades of Tyrannosaurus-Triceratops conflict was not the only legacy left by The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. O’Brien’s film represented the first time that sculpted dinosaurs were used in combination with footage of real actors. O’Brien himself got in on the action, playing hermit Mad Dick (stop laughing, this was a popular name at the time – imagine using that in 2025…) who tells Uncle Jack to look for dinosaurs. This was revolutionary for the time, opening the door for many new possibilities in the world of cinema. Pretty much every movie that features a combination of animation and live action – Star Wars, superhero films, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, etc. – can trace their origin back to The Ghost of Slumber Mountain.

Despite his talent, O’Brien was discredited by the film’s producer, Herbert M. Dawley. In addition to not financially compensating O’Brien, Dawley claimed credit for the animation and success of The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. Fortunately, other artists and filmmakers saw through the narrative created by Dawley, instead recognizing O’Brien for his unique style and talent that could be used for more ambitious projects.

Pre-Production: Magicians, Lawsuits, & Leg Injuries

Sometime after 1920, O’Brien was approached by Cathrine Curtis, a producer looking for an animator. Curtis was the filmmaking partner of producer Watterson R. Rothacker, who earlier that year had negotiated with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to purchase the rights of The Lost World with the intention of bringing Doyle’s story to the big screen. After seeing The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, Curtis brought O’Brien onboard as the animator of the film, thus setting the stage for The Lost World’s cinematic debut[vii].

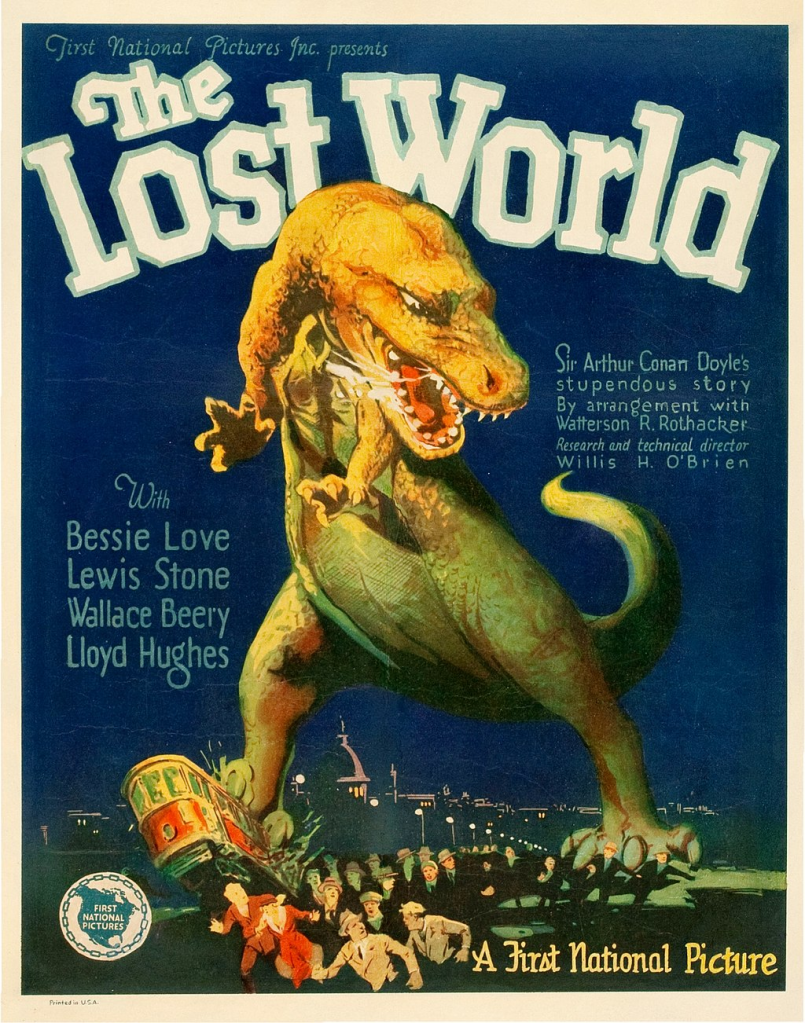

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. In 1922, after Doyle debuted test footage of The Lost World at the Society of American Magicians, Dawley sued for copyright infringement. While Rothacker eventually won the case, the legal action led to Doyle’s departure from the project prior to the conclusion of the lawsuit. In 1923, production of The Lost World resumed, with filming taking place in 1924. Actors Bessie Love (portraying Paula White), Lewis Stone (Sir John Roxton), Lloyd Hughes (Edward Malone), and Wallace Beery (Professor Challenger) were cast to bring Doyle’s characters to life, while director Harry O. Hoyt led the project.

The anticipation for The Lost World was palpable. Paleontology had been going through something of a boom in the early 1920’s, with recognizable dinosaurs like Parasaurolophus, Velociraptor, Protoceratops, Oviraptor, and Psittacosaurus being described between 1922 and 1924. These discoveries – combined with more widespread media coverage due in large part to newly installed museum displays of giants like Tyrannosaurus rex and Brontosaurus – suddenly made The Lost World a must-see film for audiences.

Multiple delays occurred in the films production, including one that was attributed to “time owing to an injury to the leg of one mighty monster, reincarnated from the Jurassic Age of 10,000,000 years ago [sic] into the twentieth century[viii].” Apparently one reporter called a Triceratops an “armadillo rhinoceros” in the lead up to the film. The next time I see a news article call a non-dinosaur a dinosaur, I’ll remind myself that journalists have always had trouble understanding what is and isn’t a dinosaur!

Release & Legacy

Finally, the day had come. On February 2nd, 1925, The Lost World made its big screen debut at the Temple Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. A week later, on February 8th, the film debuted at the Astor Theatre on Broadway, New York City.

The response to the film was overwhelmingly positive. Reviewers gushed about the fantastical animations of the film, with the dinosaurs appearing to pose a real threat to the humans they encountered. The best quote reflecting this belief came courtesy of film magazine editor Robert E. Welsh, who stated “One stamp of any of the animal’s feet and the party would be wiped out. Can you compare that thrill with anything in your experience?” In one screening in New York City, the film almost caused a riot afterwards[ix]. In total, the film grossed $1.3 million USD on a $700,000 budget, proving to be a tremendous critical and commercial success.

In the decades following the film’s release, the stop-motion techniques pioneered by O’Brien led to The Lost World being placed into the United States National Film Registry in 1998[x].According to the Oscars’ website, films selected for the National Film Registry are “based on their cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance,[xi]” signifying the importance of The Lost World to cinematic history. O’Brien’s work in cinema would continue for the next few decades, peaking with the original King Kong (1933) and the Oscar winning Mighty Joe Young (1949). Doyle would continue publishing stories until shortly before his death in 1930.

The connections between The Lost World and subsequent works are apparent. For example, the connection with the dinosaur-plagued world of King Kong is obvious, but one may consider that Charles Muntz, the adventurer gone mad in Pixar’s Up, resembles a caricature of Professor Challenger. Like Challenger, Muntz returns from South America with tales of bizarre creatures, only to be forced into returning amidst scrutiny at his discoveries. Even Marvel Comics’ Savage Land – an unexplored peninsula in Antarctica full of dinosaurs and volcanoes – shows inspiration from The Lost World, highlighting how far its influence has reached.

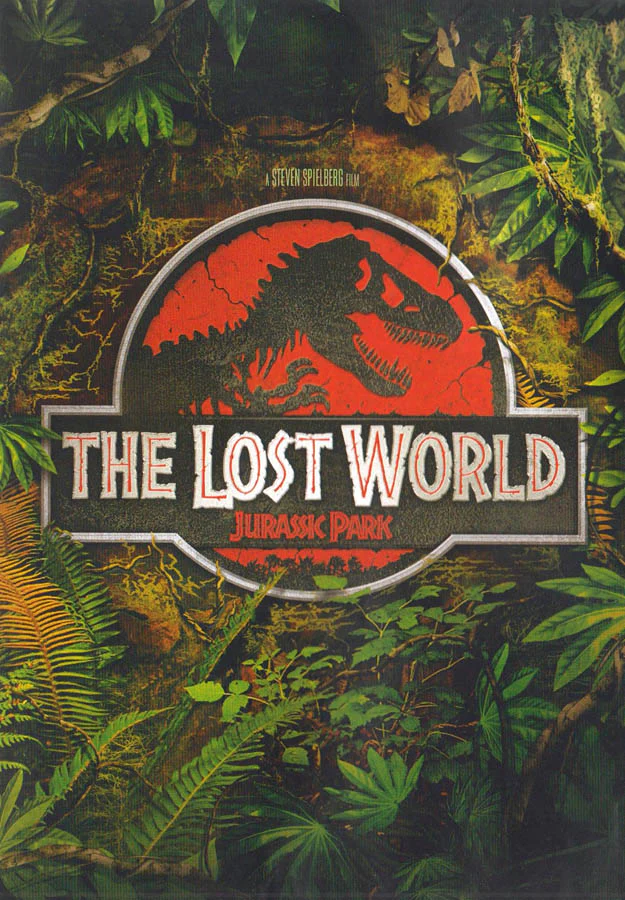

Of course, the most noteworthy production spawned from The Lost World is Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park novel and subsequent films. The setting of the first Jurassic Park – a remote island that provides a teeming paradise for long-extinct dinosaurs – is a clear derivative of The Lost World. The name of Crichton’s Jurassic Park sequel, The Lost World, pays direct homage to Doyle’s original tale as noted by Crichton himself[xii]. Since the modern dinosaur renaissance is often attributed to the success of Jurassic Park, and Jurassic Park was based largely on The Lost World, it is not a reach to say that The Lost World is directly responsible for both modern paleontological research and cinema[xiii]. Not bad for a 1925 stop motion film!

That concludes part 1! Part 2 will dive deeper into the lore of The Lost World, including a synopsis of the film, the inspiration behind Willis O’Brien’s models, and my own review of the film!

If you would like to see The Lost World for yourself, follow the link here!

Works Cited:

[i] Prothero, D. R. (2016). Giants of the Lost World: Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Monsters of South America. Smithsonian Institution.

[ii] Doyle, A. C. (1). The Lost world. 1st World Publishing.

[iii] Thomas, G. W. (2023, December 2). Lost Worlds of the Pulps – Dark Worlds Quarterly. Dark Worlds Quarterly. https://darkworldsquarterly.gwthomas.org/lost-worlds-of-the-pulps/#:~:text=The%20lost%20worlds%20of%20the,steeped%20in%20mist%20and%20mystery

[iv] Monsters, C. (2023, May 24). Willis O’Brien – Classic Monsters. Classic Monsters. https://www.classic-monsters.com/willis-obrien/

[v] The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy (1917). (n.d.). The Public Domain Review. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/the-dinosaur-and-the-missing-link-a-prehistoric-tragedy-1917/

[vi] Black, R. (2011, March 16). The Dinosaur and the Missing Link. Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-dinosaur-and-the-missing-link-97519131/

[vii] Edwards, G. (2024, October 23). The Lost World – a movie time machine adventure. The Illusion Almanac. https://illusion-almanac.com/2024/06/18/the-lost-world-a-movie-time-machine-adventure/

[viii] Edwards, G. (2024, October 23). The Lost World – a movie time machine adventure. The Illusion Almanac. https://illusion-almanac.com/2024/06/18/the-lost-world-a-movie-time-machine-adventure/

[ix] Edwards, G. (2024, October 23). The Lost World – a movie time machine adventure. The Illusion Almanac. https://illusion-almanac.com/2024/06/18/the-lost-world-a-movie-time-machine-adventure/

[x] The Times Herald from Port Huron, Michigan. (1998, November 17). Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/212381706/

[xi] https://www.oscars.org/academy-film-archive/national-film-registry

[xii] Reports, S. (1997). THE FIRST `LOST WORLD’ Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/1997/06/08/the-first-lost-world/

[xiii] Liptak, A. (2018, June 23). How Jurassic Park led to the modernization of dinosaur paleontology. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2018/6/23/17483340/jurassic-park-world-steve-bru4satte-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-dinosaurs-book-interview-paleontology

One reply on “The Complete History of The Lost World (1925): 100th Anniversary Special, Part 1”

[…] I would recommend reading that article prior to today’s installment, which can be found at the following link. Part 2 will focus on the film itself, including the plot synopsis, inspiration behind the dinosaur […]

LikeLike