Keeping up with the latest paleontology news is a challenge, even for the most dedicated of followers. So, why not make it a bit easier?

In this series of articles released at the end of each month, I will recap some of the big storylines from around the world of paleontology. Now, not every story can be covered in these articles; otherwise, you might be subject to read 10,000 words! Instead, 8-10 of the most interesting, important, or relevant storylines (as judged by yours truly) will be discussed. Some large discoveries will warrant their own separate article but will be mentioned and linked within this article as well.

Table of Contents:

- The Big News: Soft Tissues Discovered in a Jurassic Plesiosaur

- Mexidracon longiamnus, the Long-Handed Ornithomimid

- Throwing up on the Cretaceous: Fossils of Prehistoric Vomit?

- Baminornis: Archaeopteryx, but better?

- The Revival of Stygimoloch spinifer: Blown out of Proportion?

- New Australian Fossils Reveal Presence of Carcharodontosaurids, Dromaeosaurids on Continent

- Jurassic World Rebirth Trailer First Thoughts

- The Hell Creek Azhdarchid Gets a Name

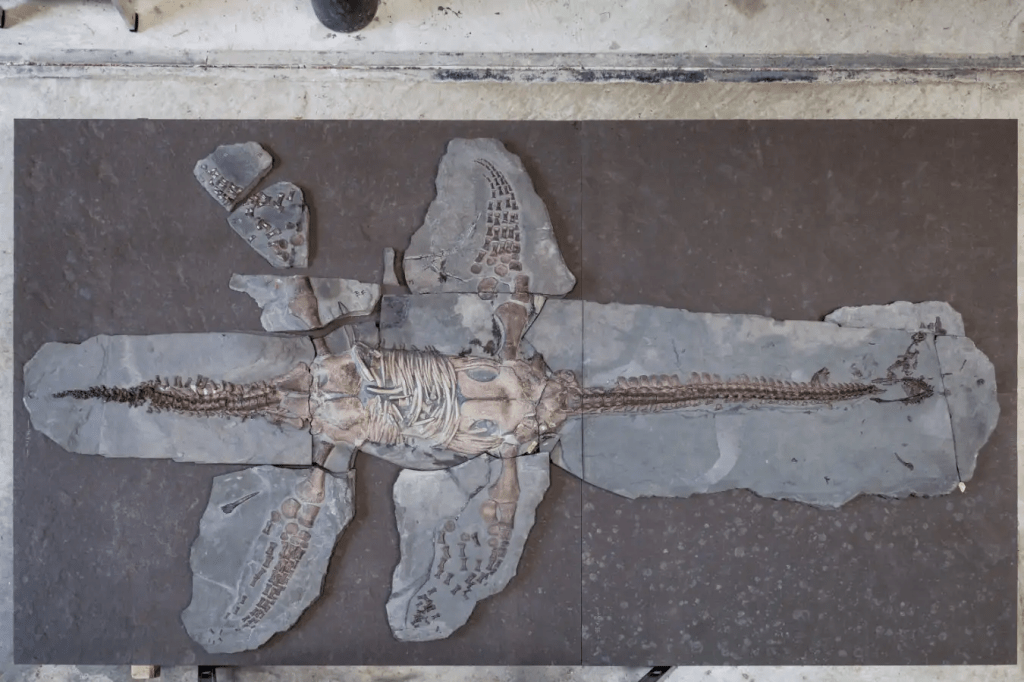

The Big News: Soft Tissues Discovered in a Jurassic Plesiosaur

European paleontologists working on an exceptional Plesiosaur specimen from southern Germany have discovered soft tissues rarely preserved in the lineage[i]. Led by Miguel Marx of Lund University, the 183-million-year-old marine reptile skeleton is nearly complete and contains traces of skin and scales preserved in extraordinary detail. The skin, which is concentrated on the hip of the Plesiosaur, is preserved in such fine detail that remnant cell nuclei and melanosomes, which can be used to interpret the animal’s colouration, are preserved. The scales are triangular, concentrated on the flippers, and bear close resemblance to turtles and some mosasaur specimens.

This fossil is incredible. While fossilized soft tissues have been associated with Plesiosaurs before, they don’t compare with those described in Marx’s paper where the internal anatomy of the skin was identified. This discovery has shed newfound light on Plesiosaur anatomy and locomotion, with the scales of the flippers believed to have been used to create lift while swimming and protect the animal while foraging on the seabed of the Jurassic. While more research is needed, the early results are nothing short of incredible.

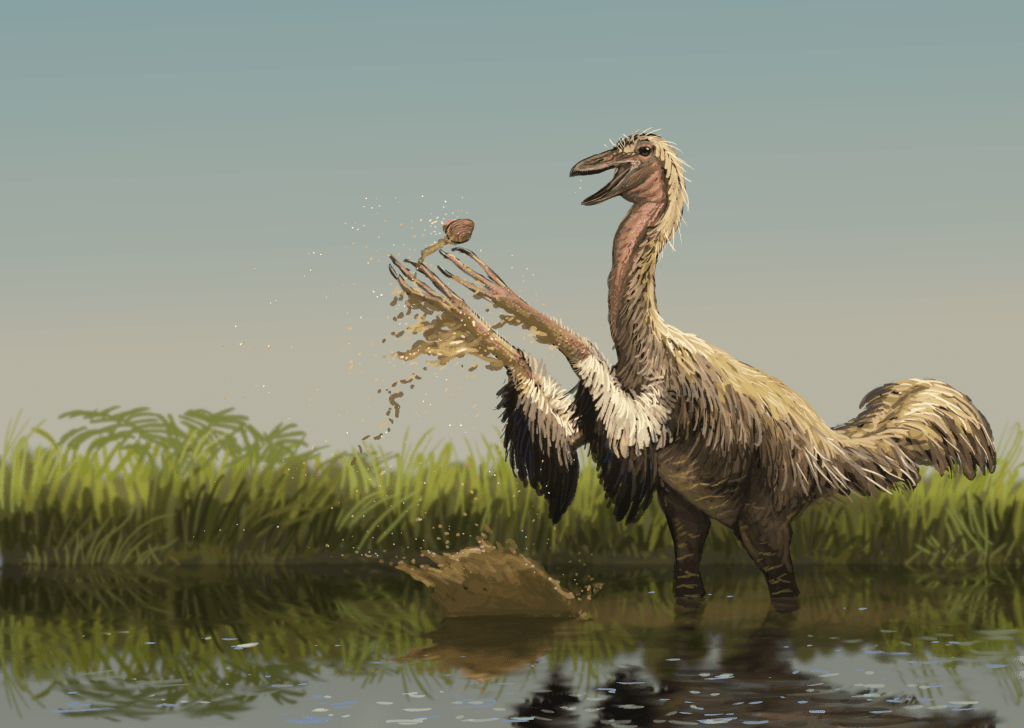

Mexidracon longiamnus, the Long-Handed Ornithomimid

Move aside, snakes; 2025 belongs to the Ornithomimids! Paleontologists led by Claudia Inés Serrano-Brañas working out of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation of Coahuila, Mexico, have described a new genus of Ornithomimid with strange forearm anatomy. Named Mexidracon longimanus, the partial skeleton of this Campanian-aged Ornithomimid (~73 million years old) bears extremely long metacarpal bones which are longer than the animals upper arm bones and the metatarsals in their feet[i].

Strangely, Mexidracon is not a Deinocheirid, the subfamily of Ornithomimids which developed long arms best represented by genera like Deinocheirus and Paraxenisaurus. The presence of such-long arms has raised questions as to what Mexidracon was using them for. Some paleontologists have floated around the idea that Mexidracon used them to probe for crustaceans and molluscs in sand, which I could get behind. My theory is that they used them like the living Aye-Ayes to scrape tree bark for insects and other small organisms. In either scenario, such appendages must have served some unique function!

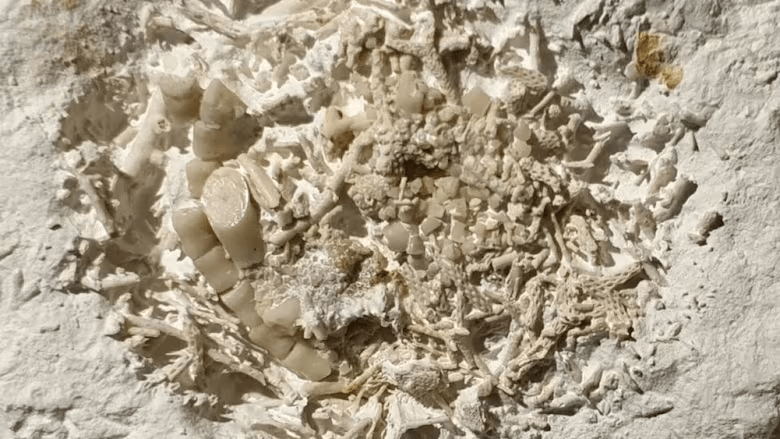

Throwing up on the Cretaceous: Fossils of Prehistoric Vomit?

Can fossilized vomit be identified? According to a new discovery in Denmark’s Stevns Klint heritage site, it certainly could! Dating back to the late Cretaceous period, the fossil contains the scattered remnants of a crinoid (or sea lily) that appears to have been regurgitated by a species of marine fish, potentially a shark[i]. Discovered by amateur fossil hunter Peter Bennicke, the specimen provides a glimpse at a unique moment in prehistory when the calcareous plates of a sea lily made a fish spill its guts.

Not all specimens need to be revolutionary to be noteworthy; sometimes, good old fashion vomit is more than enough to catch headlines!

Baminornis: Archaeopteryx, but better?

A new transitionary bird discovered in China has revealed the early evolution of the Avian lineage. Named Baminornis zhenghensis, fossils of this theropod date to the late Jurassic Period, making it one of the oldest members of clade Avialae alongside the infamous European taxa Archaeopteryx[i]. Like Archaeopteryx, Baminornis was capable of powered flight and shows a combination of features present in early birds and derived theropods, making it an important species for understanding the transition from dinosaurs to birds.

The distinction between Baminornis differs and Archaeopteryx is in the tail. Whereas Archaeopteryx contained a long, dinosaurian tail, Baminornis has a reduced structure that has become fused into a pygostyle. Its presence in Baminornis led the research team describing it, led by Runsheng Chen, Min Wang, and Liping Dong, to hypothesize that Baminornis would have been better suited for flight than its European cousin given the importance of a pygostyle in Avian flight mechanics. It goes without saying that this specimen thus marks an important transitionary event from dinosaurs to birds, given its importance to efficient flight and as pygostyles are present through modern birds

Creationists, evolution deniers, and ornithologist Alan Fedduccia often point to a lack of transitionaral fossils as evidence that birds did not descend from dinosaurs. I’d love to hear what they think of this one!

The Revival of Stygimoloch spinifer: Blown out of Proportion?

A paper describing new pachycephalosaur material attributable to Stygimoloch spinifer drew plenty of attention from the online paleo community. Described by Anton Wroblewski, the specimen of a Stygimoloch squamosal (skull bone) was discovered in the Ferris Formation of Wyoming, representing the southernmost discovered specimen of the genus[i]. More importantly, the specimen confirms that Stygimoloch are only found in the last 500,000 years of the Cretaceous, making them younger than all known Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis fossils. This provides support that the two dinosaurs are separate genera, as opposed to previous theories which posture that Stygimoloch was an immature Pachycephalosaurus.

So, why would I say this study is overblown? After talking to some people knowledgeable on Pachycephalosaurs, it seems as though this idea of a Stygimoloch-Pachycephalosaurus break has been floating around for some time. In other words, while this study formally puts the evidence of a divide into writing, the idea of Stygimoloch being valid isn’t new. Plus, the question still exists as to whether it should represent its own genus, or if it should be a second species of Pachycephalosaurus given the overall similarities between the two. There is precedent for Late Cretaceous North American dinosaurs being divided into two separate species based on their relative ages (Triceratops horridus vs T. prorsus), so this path might be more realistic for Stygimoloch.

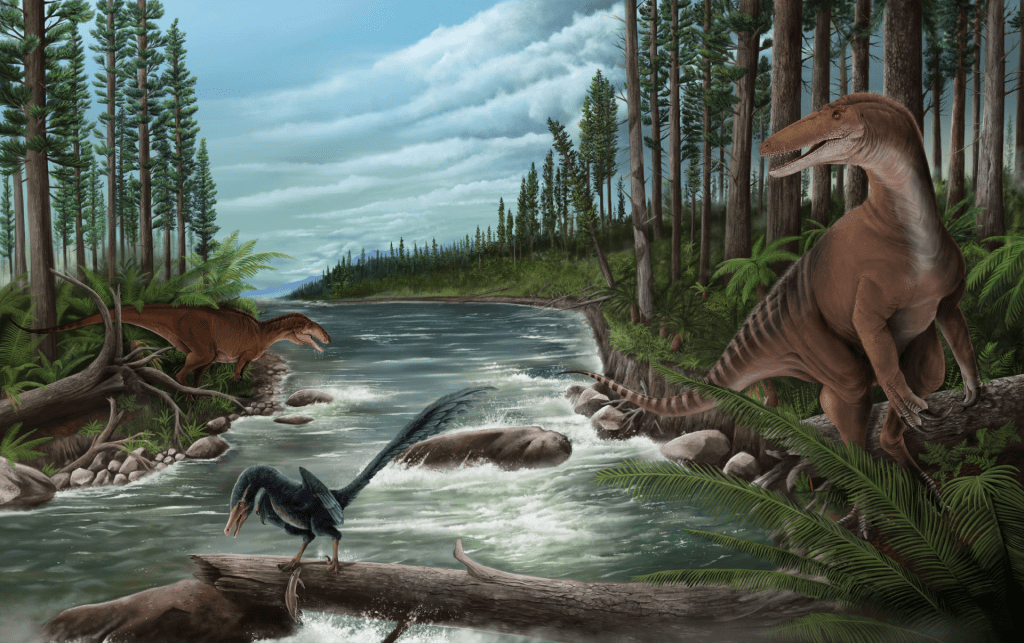

New Australian Fossils Reveal Presence of Carcharodontosaurids, Dromaeosaurids on Continent

Cretaceous Australia may not have been as isolated as previously believed, as a review of known theropod material has revealed the presence of new lineages on the continent. Led by Jake Kotevski, the study describes several bones collected from southern Australia that include isolated fossils from two large Megaraptorans, Carcharodontosaurids similar in size and anatomy to the Asian Siamraptor, and an Unenlagiine Dromaeosaur[i]. The Megaraptoran bones are the largest known on the continent, whereas the Carcharodontosaurid and Unenlagiine are the first record of the lineages in Australia.

These fossils provide a fascinating glimpse into the polar forests of Cretaceous Australia. The presence of Carcharodontosaurids and Unenlagiines confirms that dinosaurs used Antarctica as a prehistoric highway in the Cretaceous, given the presence of close relatives to these animals in South America. There are plenty of other interesting implications from this study as well, such as Megaraptorans potentially being top predators ahead of Carcharodontosaurids in some ecosystems prior to their extinction, and the oldest known record of Unenlagiinae and its implications on the family’s evolution and biogeography. Pretty impressive takeaways from only a few isolated bones!

Jurassic World Rebirth Trailer First Thoughts

The first trailer for the newest installment of the Jurassic World franchise, Jurassic World: Rebirth, dropped to mixed reactions from the paleo community. I have already talked extensively about the trailer, but I’ll recap my initial feelings. After the previous Jurassic World films, I am cautiously optimistic based on the beautiful and vibrant designs used for several returning species, namely the Tyrannosaurus rex and the Spinosaurus (minus the head). I am a little tired of the whole mutant/hybrid of doom storyline focus, but there are signs this cinematic monster could be better utilized than the Indominus rex of JW’s previous.

For my full thoughts on the Jurassic Rebirth Trailer, read the following article here at Max’s Blogosaurus: https://maxs-blogo-saurus.com/2025/02/06/jurassic-world-rebirth-trailer-should-paleonerds-care/

The Hell Creek Azhdarchid Gets a Name

Meet Infernodrakon hastacollis, the first officially named genus of pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation[i]. While Azhdarchid pterosaurs – a lineage of giants that rivaled giraffes in height and could have wingspans up to 12 meters wide – have been known to be present in Hell Creek for some time, no genus has ever been identified. Now, a study led by Henry Thomas and David Hone has finally bestowed a name upon a single cervical (neck) vertebra from Montana, USA.

2025 has been defined by the volume of new genera named from single bones. In January, the dinosauromorph Ahvaytum bahndooiveche was named from a single ankle bone, while the Carcharodontosaurid Tameryraptor was technically named from 0 bones, given that its remains blew up in WW2. Generally, it isn’t a great idea to name taxa based on single bones, which partially explains why no Hell Creek Azhdarchid had ever been described before. Regardless, it is nice to hear some of that Hell Creek Pterosaur material finally get described.

Let’s just hope Infernodrakon manages to survive the taxonomic wastebin!

Thank you for reading this article! If you would like to catch up on paleontology news from January of 2025, read the previous installment of Paleontology News here at Max’s Blogosaurus at the following link: https://maxs-blogo-saurus.com/2025/02/01/paleontology-news-january-2025/#north-america-s-oldest-dinosaur-ahvaytum

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come from the artists noted accompanying each piece. Header image courtesy of

Works Cited:

[i] Thomas, H. N., Hone, D. W. E., Gomes, T., & Peterson, J. E. 2025. Infernodrakon hastacollis gen. et sp. nov., a new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and the pterosaur diversity of Maastrichtian North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2024.2442476

[i] Kotevski, J., Duncan, R. J., Ziegler, T., Bevitt, J. J., Vickers-Rich, P., Rich, T. H., … Poropat, S. F. 2025. Evolutionary and paleobiogeographic implications of new carcharodontosaurian, megaraptorid, and unenlagiine theropod remains from the upper Lower Cretaceous of Victoria, southeast Australia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2024.2441903

[i] Wroblewski, A. F. 2024. Southernmost record of the pachycephalosaurine Stygimoloch spinifer and palaeobiogeography of latest Cretaceous North American dinosaurs. Lethaia: 57(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.18261/let.57.4.7

[i] Chen, R., Wang, M., Dong, L., Zhou, G., Xu, X., Deng, K., Xu, L., Zhang, C., Wang, L., Du, H., Lin, G., Lin, M., & Zhou, Z. 2025. Earliest short-tailed bird from the Late Jurassic of China. Nature 638(8050): 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08410-z

[i] BBC News. (2025, January 28). 66 million-year-old fossilised vomit discovered in Denmark. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp82jle12j7o

[i] Serrano-Brañas, C. I., Espinosa-Chávez, B., De León-Dávila, C., Maccracken, S. A., Barrera-Guevara, D., Torres-Rodríguez, E., & Prieto-Márquez, A. 2025. A long-handed new ornithomimid dinosaur from the Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) Cerro del Pueblo Formation, Coahuila, Mexico. Cretaceous Research, 106087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2025.106087

[i] Marx, M., Sjövall, P., Kear, B. P., Jarenmark, M., Eriksson, M. E., Sachs, S., Nilkens, K., De Beeck, M. O., & Lindgren, J. (2025). Skin, scales, and cells in a Jurassic plesiosaur. Current Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.01.001