Pachycephalosaurs have always represented something of a mystery for paleontologists. The enlarged frontoparietal domes present atop their skulls, while instantly recognizable, are the only Pachycephalosaur fossils that have been discovered with any sort of regularity. Post-cranial remains have thus remained illusive, creating significant gaps in our understanding of these dinosaurs.

Compounding the scarcity of material was an even bigger issue: the lack of any early diverging species. Most domed Pachycephalosaurs lived during the Late Cretaceous period of North America and Asia, best exemplified by genera such as Pachycephalosaurus, Stegoceras, and Prenocephale. Yet the family is believed to have diverged from Ceratopsians during the Late Jurassic, leaving a nearly 55-million-year gap between the divergence of the clade and when their first fossils appear.

That, my dear readers, is a textbook example of what paleontologists call a ghost lineage. We know that early diverging Pachycephalosaurus must have existed, but since no actual fossils had been discovered, the appearance and evolution of early dome-headed dinosaurs was largely unknown for many years.

Until now, that is, as a newly described genus has finally provided a glimpse at early Pachycephalosaurs. And what a glimpse it is:

Meet Zavacephale rinpoche, a tiny genus of Mongolian Pachycephalosaur that represents the oldest true member of the family known to science[i]. Represented by a single well-preserved specimen, fossils of Zavacephale date to the Albian Stage of the Early Cretaceous Period, approximately 108 million years ago – right in the middle of the ghost line in Pachycephalosaur fossils. As you can imagine, Zavacephale has thus proven crucial for understanding what early members of the family looked like and how Pachycephalosaurs evolved throughout the Cretaceous period.

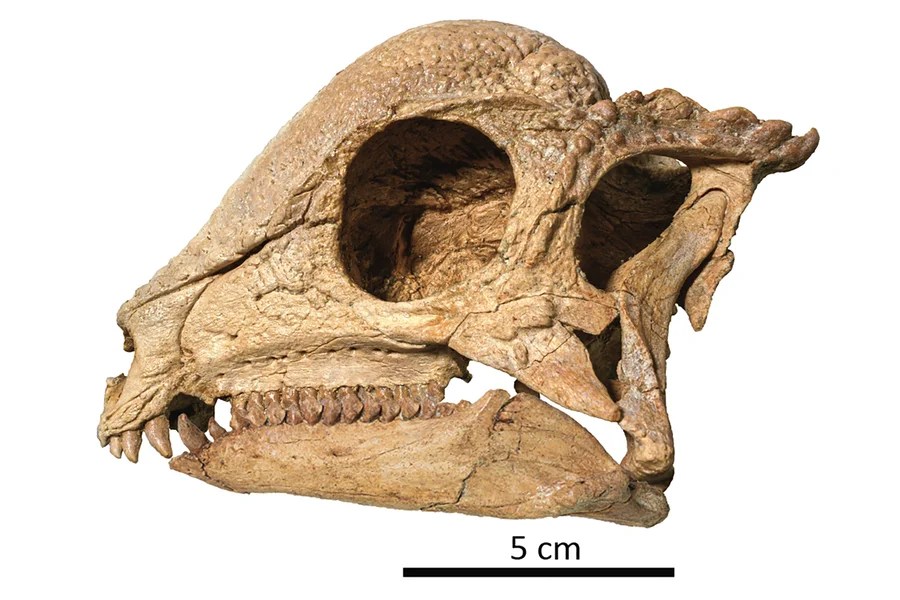

Let’s start with the most prominent feature of Pachycephalosaurs: the skull. While Zavacephale predates other Pachycephalosaurs by over 20 million years, it nonetheless possessed the enlarged, well-developed skull dome characteristic of its cousins. As in other Pachycephalosaurs, the frontal bones atop the skull have become raised into a convex shape, with small bony ornaments present on the lateral margins of the squamosal. At first, you might assume this means the dome is equivalent to what we see in younger taxa. Yet closer investigation has revealed this was not the case, particularly as it pertains to the parietal region of the skull.

In younger taxa, the dome is comprised of two bones, the frontals and parietals, which both make significant contributions to the structure. In Zavacephale, the parietal bones are quite small compared to the frontals, which differs significantly from younger taxa. The rear margins of the parietals in Zavacephale provide another key difference, as the bony ornamentation present on the posterior parietal margins of younger Pachycephalosaurs is completely absent in Zavacephale. Additionally, the temporal fenestrae of Zavacephale are large, which is uncommon in younger taxa whose openings are typically minimal.

When put together, we can see that the skull Zavacephale has an intermediate anatomy between younger Pachycephalosaurs and non-Pachycephalosaur marginocephalians. As such, the dome of Zavacephale has provided paleontologists with key insights into how the structure evolved in the clade. We can now reason that the frontal evolved a dome-like condition first, with the parietal following later in the evolutionary process and bringing more complex ornamentation along with it.

The post-cranial remains of Zavacephale are just as important. The holotype of Zavacephale, MPC-D 100/1209, is represented by over 50% of bones in the skeleton. This may not seem like that much, but rather shockingly it represents the most complete Pachycephalosaur skeleton ever discovered! Elements from both forelimbs and hindlimbs, tail, and the pelvic girdle are present, with the first record of a Pachycephalosaur hand in the fossil record. If you thought the fossil record of Spinosaurids was bad, Pachycephalosaurs are a whole other beast!

The first important feature of the skeleton is the tail, which is articulated and complete in Zavacephale. Running throughout the tail are fossils of small, ossified tendons known as myorhabdoids, which are associated with supports in the musculature of the tail[ii]. While myorhabdoids have been documented in Pachycephalosaurs before, no other terrestrial vertebrate lineage possesses this trait[iii]. While the function of these tendons has been debated, it has been theorized that they may have aided Pachycephalosaurs in ‘tripoding’ or using their tail almost like a third limb to rear upwards. This may have helped Pachycephalosaurs with scanning the environment for predators, reaching higher vegetation, or other nefarious purposes that are presently unknown – or unpublished.

More important information has been gained from the internal anatomy of Zavacephale. Osteohistology performed on the specimen has revealed it was immature at the time of death, aged only 2 years old and still growing. Like human teenagers, this immaturity is reflected in the anatomy of the skeleton, whose long, gangly limbs contrast a relatively tiny meter-long body that only weighed ~5.85 kilograms (12.9 pounds) when alive. Yet the developed dome of Zavacephale suggests it still would have been reproductive, as the domes of Pachycephalosaurs are theorized to have been used for sociosexual selection in mature animals. Thus, Zavacephale and other Pachycephalosaurs were likely sexually mature before their bodies were fully grown, a trend which is observed in other dinosaurs but contrasts birds, who often reproduce only after they have reached skeletal maturity[iv].

Another odd feature of Zavacephale comes not from the skeleton itself, but rather what was inside of it. Within the stomach cavity of Zavacephale was an accumulation of small stones known as gastroliths that would have aided the digestive process. This feature is not particularly abnormal, as many different dinosaur families (including modern birds) have been documented using gastroliths to help process food. However, the gastroliths present in Zavacephale are quite angular, which the authors describing the taxon believe to be a sign of an omnivorous diet. The teeth of Zavacephale may support this claim, as the front of the dentary sports enlarged borderline caniniform teeth. This claim is acknowledged to be imperfect, however, and should be taken with several grains of salt.

The importance of Zavacephale to Pachycephalosaur research cannot be understated. The lone specimen represents both the oldest and most complete Pachycephalosaur in the fossil record, providing new information into the evolution of the clade, post-cranial anatomy, and reproductive behaviours.

For a lineage with few well-preserved remains, Zavacephale has set the new bar for Pachycephalosaur skeletons – one that may not be touched anytime soon!

Thank you for reading this article! I am fortunate enough to work with two of the foremost Pachycephalosaur experts on Earth, and to say their excitement at this discovery was infectious would be underselling it! I apologize for the lack of articles in recent months; I have been quite busy with other matters, including my first research paper which *hopefully* will be published soon. Until then, take care!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the sources noted alongside each piece.

Header image comes courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, found here.

Works Cited:

[i] Tsogtbaatar, K., Chinzorig, T., Takasaki, R., Yoshida, J., Tucker, R. T., Buyantegsh, B., Mainbayar, B., & Zanno, L. E. 2025. A domed pachycephalosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09213-6

[ii] Brown, C. M., & Russell, A. P. 2012. Homology and architecture of the caudal basket of Pachycephalosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia): The first occurrence of myorhabdoi in Tetrapoda. PLoS ONE, 7(1), e30212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030212

[iii] See above.

[iv] Erickson, G. M., Rogers, K. C., Varricchio, D. J., Norell, M. A., & Xu, X. 2007. Growth patterns in brooding dinosaurs reveals the timing of sexual maturity in non-avian dinosaurs and genesis of the avian condition. Biology Letters, 3(5), 558–561. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2007.0254