The defining characteristic of one prehistoric reptile may also have been a prime target for its predators.

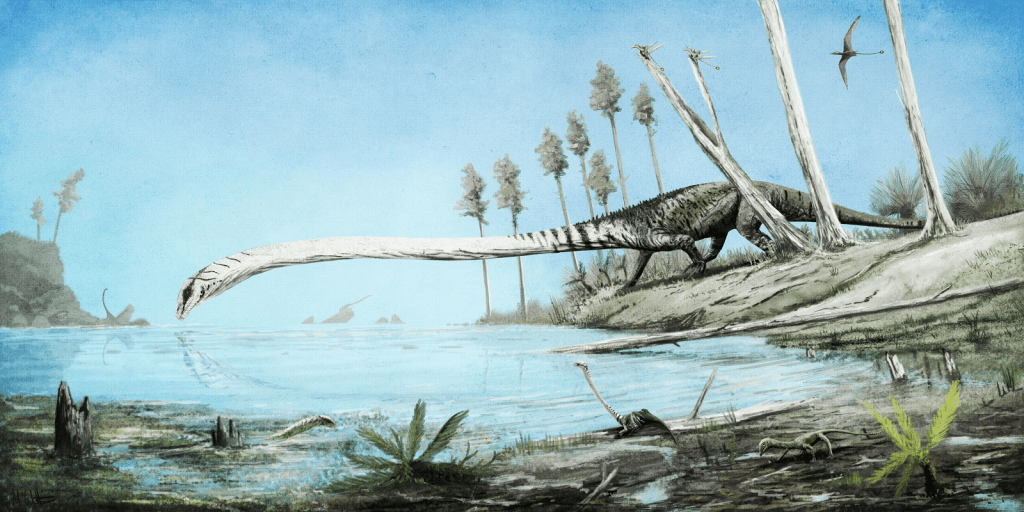

Few prehistoric animals were stranger than the aquatic Tanystropheids. At the dawn of the Triassic Period, some 247 million years ago, these reptiles evolved cartoonishly large necks that were seemingly too large for reality. Headlining these noodle-necked reptiles was their namesake, Tanystropheus, a predator whose neck accounted for more than half its total body length[i]. Tanystropheus is accepted as having the longest neck proportionate to the rest of its body in Earth’s known history[ii], putting competitors like the sauropod dinosaurs and plesiosaurs to shame.

While this feature aided Tanystropheus in hunting aquatic prey, recent studies have revealed it may have come at a cost. Analysis of two bodyless Tanystropheus specimens housed in Switzerland has revealed the presence of bite marks where the neck ends, indicating they were attacked and decapitated by a predator[iii]. Talk about a grizzly ending!

The wounds are so extensive that researchers Stephan Spiekman and Eudald Mujal have devised a method of attack. They proposed that the predators attacked Tanystropheus from above, delivering a massive bite and pulling their prey backwards[iv]. While this theory is speculative, it provides an interesting insight into how our prehistoric noodles were turned into inverse Ichabod Cranes.

The existence of these specimens – which are from different Tanystropheus species – indicates that attacks like these may have been a common occurrence for the entire genus. With such a large and conspicuous neck, it must have been seen as an easy target for predators. It didn’t help that its neck was slender, weak (due to relatively few and proportionally long vertebrae), and inflexible, making it an ideal target for predators.

On the topic of predators, one question remains: who was the killer? No teeth were preserved alongside the severed heads, meaning the killer’s identity cannot be confirmed with certainty. Spiekman and Mujal did name a few candidates, including the aquatic reptiles Nothosaurus and Helveticosaurus, the early Ichthyosaur Cymbospondylus, or a carnivorous fish (early sharks were around at this time). It could have been a terrestrial predator too, given that the extent of Tanystropheus’ aquatic behaviours has been debated[v]. I would put my money on Cymbospondylus, though the terrifying visage of Helveticosaurus does give me pause…

Despite the flashing neon sign saying “eat me” that was its neck, Tanystropheus was a very successful genus. Its fossils are found across the northern hemisphere, comprise multiple species, and span over 15 million years of geological time. While their fragile necks may have occasionally subjected them to violent predation, it didn’t prevent them from becoming one of the most widespread reptiles of the early Triassic.

Thank you for reading this article! If you’re interested in marine reptiles, I suggest you read about the Mosasaur’s potential secret weapon, here at Max’s Blogosaurus!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article.

[i] Naish, Darren. Ancient Sea Reptiles: Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs, and More. Smithsonian Books, 2023.

[ii] De Souza, Ray Brasil, and Wilfried Klein. “Modeling of the Respiratory System of the Long-Necked Triassic Reptile Tanystropheus (Archosauromorpha).” The Science of Nature, vol. 109, no. 6, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-022-01824-7.

[iii] Spiekman, Stephan N.F., and Eudald Mujal. “Decapitation in the Long-Necked Triassic Marine Reptile Tanystropheus.” Current Biology, vol. 33, no. 13, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.027.

[iv] Black, Riley. New Evidence of Decapitations Points to This Triassic Predator’s Fatal Flaw, 6 July 2023, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/premium/article/decapitations-point-to-long-neck-predators-fatal-flaw.

[v] Formoso, Kiersten, et al. “A Long-Necked Tanystropheid from the Middle Triassic Moenkopi Formation (Anisian) Provides Insights into the Ecology and Biogeography of Tanystropheids.” Palaeontologia Electronica, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.26879/988.