There’s nothing more embarrassing than getting caught doing something you shouldn’t be doing.

Especially when it becomes immortalized for 67 million years.

During the Mesozoic epoch, sauropod dinosaurs would have provided plenty of food for predators across the world. The massive carcass of one adult could likely keep an entire ecosystem fed for weeks, while young sauropods were plentiful and easy prey. The discovery of massive communal nesting sites in places like Argentina and India indicates that thousands of baby sauropods would have hatched together, providing a prehistoric smorgasbord for predators to take advantage of.

And take advantage they did.

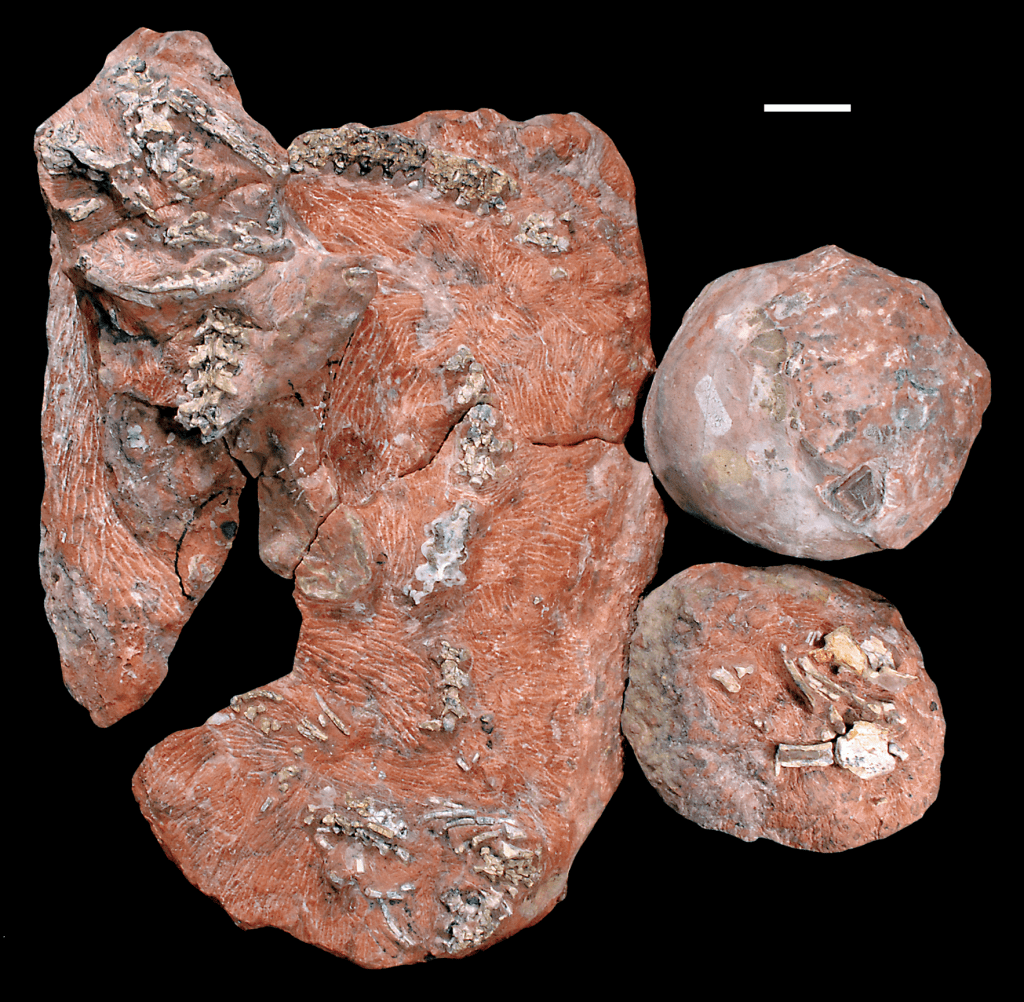

Nowhere is this more apparent than in a fossil nest from western India. Discovered in 1984 by paleontologist Dhananjay Mohabey, the nest was considered unremarkable due to how common sauropod nests were in the region. It would be placed in storage at the Geological Survey of India until 2001 when paleontologist Jeffrey Wilson became intrigued by the specimen and re-examined the remains alongside Mohabey[i].

What they found was astonishing: curled up alongside the clutch of eggs and one new hatchling were the remains of a prehistoric snake[ii]. Snake fossils are rare due to their loosely articulated and fragile skeleton, making the preservation of an articulated snake engaging in active feeding behaviours even more special. In 2010, Wilson and Mohabey named their ancient egg thief Sanajeh indicus, which translates to “ancient gape” (presumably based on egg-eating abilities). It’s a shame the name Oviraptor (“Egg Thief”) was taken…

Like Oviraptor, the name Sanajeh is misleading. While modern snakes can stretch their jaws to swallow eggs whole, the skeleton of Sanajeh indicates it was incapable of practising such a behaviour[iii]. Instead, it has been proposed that Sanajeh constricted the sauropod eggs and fed on the contents within or waited until the babies hatched before striking. Given the presence of a fledgling hatchling alongside Sanajeh, it seems that the latter is more likely for the holotype specimen.

Supplemental discoveries have revealed that this was not a one-off behaviour, as more Sanajeh specimens have been found associated with sauropod nests. This behaviour was clearly beneficial for the snakes, as Sanajeh could grow to 3.5 meters long (which is comparable to some of the longest modern snakes). While baby sauropod buffets weren’t their only source of food in prehistoric India, they made for a plentiful and easy meal for these titanic serpents.

Thank you for reading today’s article, and happy world snake day! While many among us may despise these noodle-like reptiles (looking at you, Indiana Jones), they are one of the more fascinating reptile families on Earth. Think about it: these animals can see in infrared, produce venom (sometimes), and evolved to abandon legs! Quite the marvels of evolution if you ask me!

If you’re interested in a close relative of Sanajeh, I suggest you read about Madtsoia and the wildlife of Prehistoric Madagascar here at Max’s Blogosaurus!

I do not take credit for any image found in this article. Header Image Courtesy of Julius Csotonyi, whose terrific work can be found here.

Works Cited:

[i] Yong, Ed. “Sanajeh, the Snake the Ate Baby Dinosaurs.” Science, 3 May 2021, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/sanajeh-the-snake-the-ate-baby-dinosaurs.

[ii] Kaplan, Matt. “The Snake That Swallowed Dinosaurs.” Nature, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2010.98.

[iii] Lomax, Dean R., and Bob Nicholls. Locked in Time: Animal Behavior Unearthed in 50 Extraordinary Fossils. Columbia University Press, 2022.

One reply on “World Snake Day: Sanajeh, The Snake That Got Caught in the Act”

[…] © Max’s Blogo-Saurus […]

LikeLike