Few prehistoric animals are as mysterious as Tullimonstrum gregarium, an ancient marine animal related to… what, exactly?

The short answer is that nobody knows. A better one is that many people claim to know – but none know for sure.

Let’s start at the beginning. In 1955, professional pipefitter and amateur fossil hunter Francis Tully discovered something special while exploring The Mazon Creek fossil beds in Illinois, USA. While the specimen was only about a foot long (~30 centimetres), it belonged to a strange marine animal unlike any other. When paleontologists from the Field Museum of Chicago examined the fossil, they were stumped by its unique appearance and puzzled over its relationships to other animals. After presumably pondering the creature’s existence for years, the Field Museum’s invertebrate fossil curator Eugene Richardson named the fossil Tullimonstrum gregarium in 1966, better known as the Tully Monster.

A Species Unlike any Other

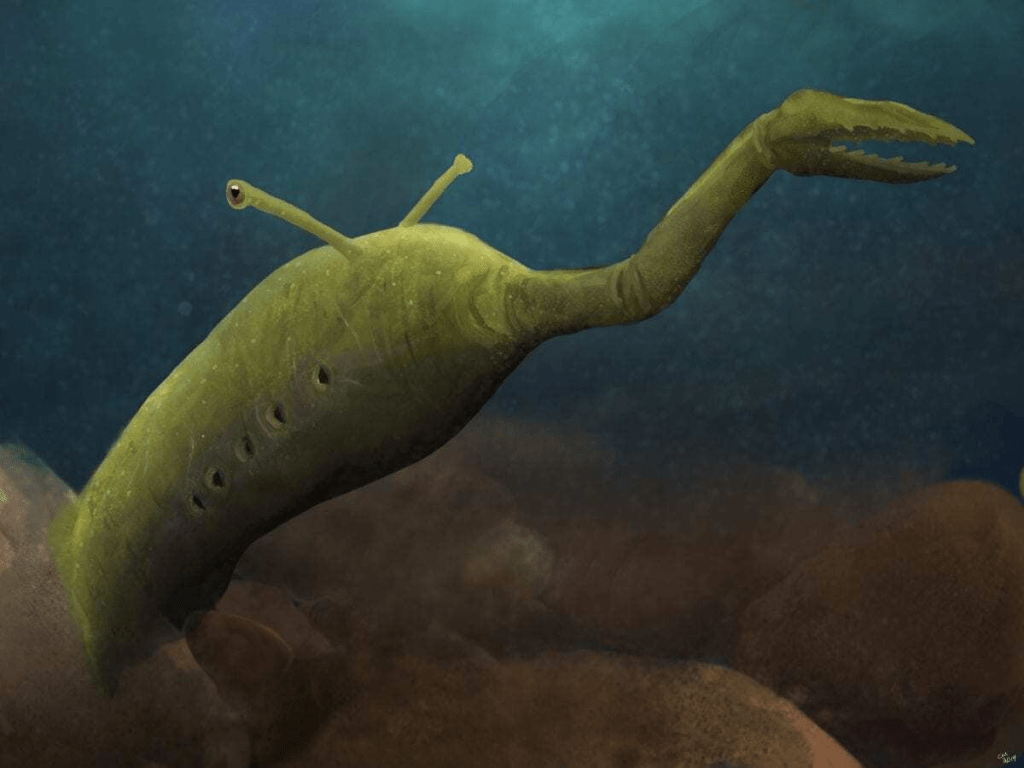

To understand why the Tully Monster is such a challenging species for paleontologists to analyze, we must first examine its appearance. The body of Tullimonstrum was cylindrical, ending with a triangular caudal (tail) fin that would have propelled it through the ancient oceans of our planet. Not too strange yet, but don’t worry; the best is about to come.

Meet the Tully Monster! ©Orribec on twitter

At the front of the Tully Monster was a long proboscis (or elongated feeding appendage) that extended from its head. While this isn’t necessarily the strangest thing in the world, the fact that the appendage is capped by a primitive jaw-like structure – which could contain up to 8 needle-like teeth – certainly is. Though a tooth-bearing jaw positioned so far away from its head may have allowed Tullimonstrum to pluck prey from open waters, paleontologists are uncertain if they were active predators or scavengers[i].

Even stranger are the eyes of Tullimonstrum. Instead of being found on their main body, they were positioned on an eyestalk protruding from the top of their heads. This wouldn’t have been a mobile apparatus, instead forming a rigid rod-like structure that kept their eyes firmly in place. Some studies of their eyes indicate they may have had a camera-like ability to perceive the world around them, which could mean they were active predators in their ecosystems[ii]. Put all the Tully Monster’s bizarre traits together, and you end up with a strange animal once described as a “pregnant earthworm with fins and an elephant snout” – and for good reason![iii]

What Exactly are you, oh Great Tully Monster?

Paleontologists may know what Tullimonstrum looked like, but its relationship to other animals has long been mysterious. At various times, the Tully Monster has been lumped in with ribbon worms, mollusks (snails and ancestors), cephalopods (squids, octopi, and ancestors), extinct eel-like animals known as Conodonts, ancient arthropods (like the Cambrian Opabinia), and primitive vertebrates like Lampreys. That’s quite a list!

When it was first described, paleontologists were so confused by its relationships that they refused to assign it a clade, which is rare to see in scientific literature[iv]. Wikipedia, which usually provides a detailed chart of every animal’s taxonomy, only goes so far as to place Tullimonstrum within Bilateria. A good start, perhaps, but when you realize that Bilateria contains 99% of all animals, it suddenly becomes less impressive. I suppose it’s better than nothing…

So, what was the Tully Monster? In recent years, numerous studies have tried to find the answer. In 2016, the answer seemed to be that Tullimonstrum was a member of Cyclostomata, the most primitive group of vertebrates that includes extant Lampreys and Hagfish. A study conducted by paleontologist Victoria McCoy associated a supposed “gut trace” present in the fossils of Tullimonstrum with the notochord, the rod structure in vertebrates that acts as a precursor to the spine[v]. This feature – alongside the presence of a tri-lobbed brain, a tail with fin rays, teeth, and a separate 2016 study which found the eyes of Tullimonstrum to be like vertebrates[vi] – was enough for McCoy to believe that Tullimonstrum should be in Cyclostomata, making it a primitive vertebrate.

This view would not last. In 2017, a counter-study disputed the results of both 2016 studies. University of Pennsylvania paleontologist Lauren Sallan and company questioned McCoy’s identification of the gut trace as a notochord, noting that the structure extends past the Tully Monster’s eyes, something not observed in any vertebrate[vii]. The fact that contemporary soft-bodied organisms lack preserved notochords cast doubt upon McCoy’s identification, suggesting that the structure represented something else.

Additionally, Sallan’s study disputed the other connections between the Tully Monster and primitive vertebrates. The supposed tri-lobbed vertebrate brain had numerous traits akin to mollusks, and the tail fins were more similar to the Cambrian Anomalocaridids. Other issues were noted in the jaws, which were found to be unlike those of lampreys, and in the eyes, where the critical diagnostic traits were not found consistently present in vertebrates[viii]. The study didn’t outright reclassify Tullimonstrum, but it cast plenty of doubt upon vertebrate affiliations for our strange creature.

This would become a recurring theme in Tully Monster research. A 2019 study against vertebrate classification noted similarities between Tullimonstrum eye pigmentation and cephalopods, suggesting it may have been an invertebrate[ix]. McCoy returned to the discourse in 2020, authoring a study that utilized advanced spectroscopy (measuring wavelengths emitted by surfaces) to analyze the organic matter of Tullimonstrum, finding it to be a vertebrate[x]. The latest Tullimonstrum study – published by Japanese paleontologist Tomoyuki Mikami in April 2023 – provided another critique of the vertebrate hypothesis, posturing that Tullimonstrum was an invertebrate but not one with a discernable lineage[xi]. For paleontology fans, the Tully Monster’s constant cycle of study followed by counter-study may sound a little familiar…

Note to self: do not fall into the Tully Monster rabbit hole like you did with Spinosaurus. Please, for the love of God, I can’t do this for two different species!

So, where does this leave us? It’s very unclear. The most likely answer is that Tullimonstrum was a vertebrate relative, perhaps a member of Cyclostomata or the ever more primitive chordate lineage Cephalochordata, which includes animals like the Amphioxus. Tullimonstrum was far longer and more developed than any living Cephalochordate, making it a strange placement for the enigmatic species. Cephalopods are another intriguing possibility, but until further research provides a thorough and accepted result, the answer will remain unclear…

An Illinois Speciality

While the Tully Monster is known from hundreds of specimens, they all come from the Mazon Creek locality. It wasn’t the only animal unique to Mazon Creek; fossils of many soft-bodied organisms, such as the cartilaginous fish Bandringa and the sea anemone Essexella, are common in Mazon Creek but not found elsewhere.

The ancient environment of Mazon Creek allowed for the preservation of these unique animals. During the Carboniferous period when Tullimonstrum and company lived, about 307 million years ago, Mazon Creek was a shallow sea overlain by a tropical climate. When marine animals died, their bodies became buried and were partially consumed by bacteria, releasing carbon dioxide into the surrounding sediment. The released carbon dioxide bonded to iron in the sediment, forming concretions around the organism that later lithified[xii]. This process enabled the exceptional preservation of many soft-bodied organisms when they would have decayed in typical preservation environments.

For now, Mazon Creek and the state of Illinois are the only known home of Tullimonstrum. The people of Illinois are proud of this fact, demonstrated by the fact that Tullimonstrum became the official Illinois state fossil in 1989. Some Illinois U-Haul trucks even have a graphic of Tullimonstrum printed on their cab, highlighting the special relationship between the state and their prized fossil.

The Cryptid Connection…

The Tully Monster looks like a work of science fiction, which may explain why Cryptozoologists have become enamoured by it. For reference, Cryptozoology studies mysterious and legendary creatures like Bigfoot and the Chupacabra. The strange appearance of the Tully Monster and its unclear evolutionary relationships have made it a perfect candidate for this field despite its extinction over 300 million years ago.

Cryptozoologists have often connected the Tully Monster to the infamous Loch Ness Monster. The peak of this connection came in 1968 when Nessie journalist Frederick “Ted” Holiday published a book called “The Great Orm of Loch Ness,” connecting the Tully Monster to Scotland’s infamous monster. Other aquatic cryptids, such as the European Lindworm, have also been associated with the Tully Monster. I get a good laugh from thinking that an extremely restricted, 1-foot-long Carboniferous species not only survived into the present but travelled to northern Europe and grew exponentially in length!

The Cryptid status of the Tully Monster perhaps peaked in the 1960s with an elaborate hoax. After Field Museum paleontologist Eugene Richardson described Tullimonstrum in 1966, he received multiple letters from Kenya describing a creature eerily similar to the Tully Monster. The letters, which came from a vast demographic including schoolchildren and retired Colonels, all described a “dancing worm” with a long snout and a bite fatal to humans living in the Turkana county of Kenya. The correspondence was so credible that Richardson considered launching expeditions to find the Dancing Worm of Turkana. If only Jeremy Wade was around to help!

Fortunately, the hoax was uncovered before an expedition could be launched. It turned out that the letters were all courtesy of one man: Dr. Brian Patterson, the former Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Field Museum. Patterson knew of Richardson’s research and used a man on the inside at the Field Museum to execute the prank and ensure that Richardson didn’t go through with his expedition[xiii]. The icing on the cake came in 1968 when Patterson sent Richardson a photo of himself in hunting attire holding a freshly caught Tullimonstrum! Luckily for Patterson, Richardson had a good sense of humour about the prank and would publish a short book about the ordeal in 1969, which can be read at this link.

To Conclude…

The Tully Monster is perhaps one of the most enigmatic extinct species known to science. Its bizarre traits have turned it into a prehistoric Rorschach test, a strange amalgamation of different animals that can’t confidently be placed in any lineage. Think about it; what other animal is so bizarre that experienced paleontologists would consider launching an expedition to rural 1960s Kenya on the slight chance it may be there? If that doesn’t demonstrate an otherworldly command over the minds of paleontologists, I don’t know what does!

Thank you for reading this article! Luckily for Eugene Richardson, nothing came of the dancing worm hoax. Other times, paleontologists haven’t been quite as lucky, including National Geographic in 1999. If you want to learn how a supposed rare Chinese dinosaur specimen tricked the institution, try reading “Archaeoraptor and the Great Dinosaur Hoax” here at Max’s Blogosaurus!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. The header artwork comes courtesy of Julio Lacerda, whose work can be found at his tumblr linked here.

Works Cited:

[i] “Tully Monster Mystery Solved, Scientists Say.” Scientific American, 17 Mar. 2016, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/tully-monster-mystery-solved-scientists-say.

[ii] Clements, Thomas, et al. “The Eyes of Tullimonstrum Reveal a Vertebrate Affinity.” Nature, vol. 532, no. 7600, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Apr. 2016, pp. 500–03. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17647.

[iii] “Francis Tully Dies; Discoverer of ‘Tully Monster’ – Los Angeles Times.” Los Angeles Times, 13 Sep. 1987, http://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-09-13-me-7548-story.html.

[iv] Black, Riley. “What Is a Tully Monster? Scientists Finally Think They Know.” Smithsonian Magazine, 16 Mar. 2016, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-tully-monster-scientists-finally-think-they-know-180958422.

[v] Black, Riley. “What Is a Tully Monster? Scientists Finally Think They Know.” Smithsonian Magazine, 16 Mar. 2016, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-tully-monster-scientists-finally-think-they-know-180958422.

[vi] Clements, Thomas, et al. “The Eyes of Tullimonstrum Reveal a Vertebrate Affinity.” Nature, vol. 532, no. 7600, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Apr. 2016, pp. 500–03. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17647.

[vii] Switek, Brian. “Tully Monster Still a Mystery.” Scientific American Blog Network, 15 Mar. 2017, blogs.scientificamerican.com/laelaps/tully-monster-still-a-mystery/?_gl=1*xqj5k3*_ga*Mzc2NDk3MTI0LjE2OTEzNDA5ODQ.*_ga_0P6ZGEWQVE*MTY5NDYzMzM5NC43LjEuMTY5NDYzNDk5NC42MC4wLjA.

[viii] Sallan, Lauren, et al. “The ‘Tully Monster’ Is Not a Vertebrate: Characters, Convergence and Taphonomy in Palaeozoic Problematic Animals.” Palaeontology, edited by Xi-Guang Zhang, vol. 60, no. 2, Wiley, Feb. 2017, pp. 149–57. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12282.

[ix] Rogers, Christopher S., et al. “Synchrotron X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy of Melanosomes in Vertebrates and Cephalopods: Implications for the Affinity of Tullimonstrum.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 286, no. 1913, The Royal Society, Oct. 2019, p. 20191649. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1649.

[x] McCoy, Victoria E., et al. “Chemical Signatures of Soft Tissues Distinguish Between Vertebrates and Invertebrates From the Carboniferous Mazon Creek Lagerstätte of Illinois.” Geobiology, vol. 18, no. 5, Wiley, Apr. 2020, pp. 560–65. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12397.

[xi] Tamisiea, Jack. “Was The Tully Monster a Fish, a Worm, a Giant Slug With Fangs?” Scientific American, 19 Apr. 2023, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/was-the-tully-monster-a-fish-a-worm-a-giant-slug-with-fangs.

[xii] Clements, Thomas, et al. “The Mazon Creek Lagerstätte: A Diverse Late Paleozoic Ecosystem Entombed Within Siderite Concretions.” Journal of the Geological Society, vol. 176, no. 1, Geological Society of London, Oct. 2018, pp. 1–11. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2018-088.

[xiii] “Mazon Monday #50: The Dancing Worm of Turkana #MazonMonday #MazonCreek #TullyMonster.” ESCONI, 8 Mar. 2021, www.esconi.org/esconi_earth_science_club/2021/03/mazon-monday-50-the-dancing-worm-of-turkana-mazonmonday-mazoncreek-tullymonster.html.

2 replies on “What was the Tully Monster?”

[…] Thank you for reading today’s article! The field of paleontology contains many mysteries, including one of the strangest animals to live on Earth, the Tully Monster. Was this aquatic creature a worm, a lamprey, or something else entirely? If you would like to know, read about it here at Max’s Blogosaurus! […]

LikeLike

[…] surrounding it – just like the Tully Monster. Was it a lamprey? A slug? A squid? Read “What was the Tully Monster?” to find […]

LikeLike