Dear Reader,

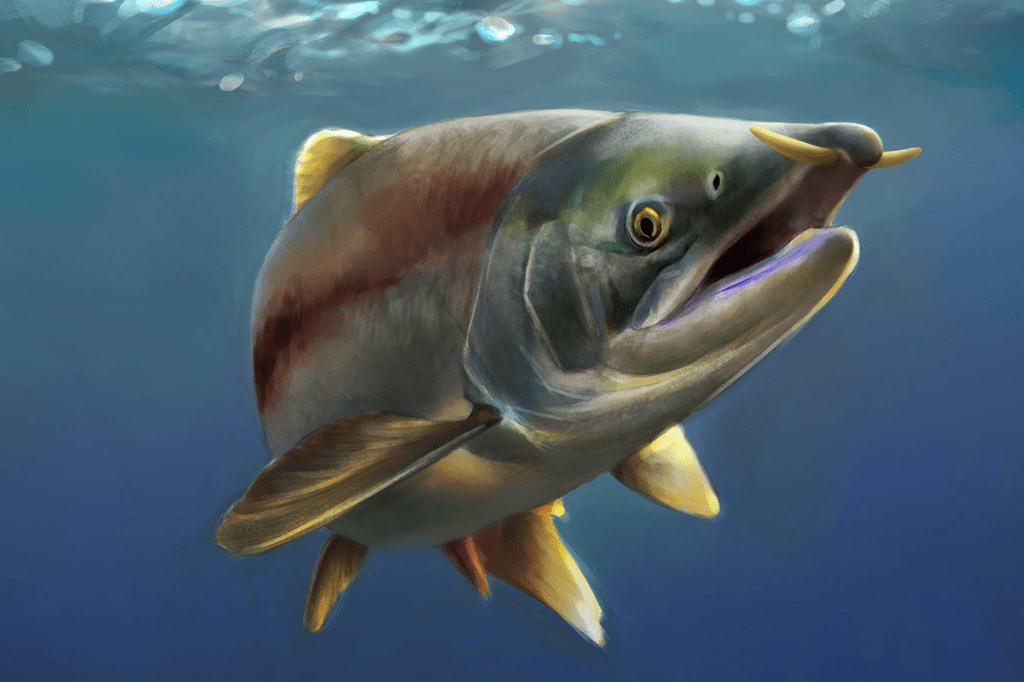

We are gathered here to celebrate the life and title of Oncorhynchus rastrosus, better known as the sabre-toothed salmon. Since its publication in 1972, a pair of large “fangs” associated with this Pacific native have resulted in frequent comparisons with mammalian carnivores like Smilodon and Thylacosmilus, sabre-toothed predators thought to possess a similar dental arrangement to the giant fish. Sadly, recent discoveries and subsequent analyses have proven these assumptions to be false, resulting in the retirement of the legendary sabre-toothed salmon moniker.

RIP to the sabre-toothed salmon! Long live the spike-toothed salmon!

When the rossils of O. rastrosus were first discovered, paleontologists theorized that their enlarged fangs would have pointed downwards into their jaws during life. Despite the teeth not being found in this placement, this was a perfectly sound conclusion to make. Extant members of the genus Oncorhynchus, which comprise twelve different species of Pacific Salmon and Trout, feature this dental arrangement. Why would O. rastrosus be any different?

In the decades following its initial description, the lack of an articulated skull led to O. rastrosus becoming well-known as the sabre-toothed salmon. Any discussions of sabre-toothed prehistoric animals were incomplete without mentioning the legendary salmon, a fish that never felt out of place when discussed alongside animals like Gorgonopsids or sabre-toothed cats. I always took great joy in presenting O. rastrosus to those blissfully unaware, as it’s strange dental configuration and massive size (estimates range between 2.4-2.7 meters long at maximum) turned the sabre-toothed salmon into my favourite species of prehistoric fish.

Which made the new developments surrounding O. rastrosus even more tragic. In my eyes, at least…

On April 24th, 2024, paleoecologist Kerin Claeson and a team of researchers published a new paper examining the appearance and life history of O. rastrosus. On top of re-examining the existing fossil material, Claeson et al. describe two new specimens discovered near the town of Gateway, Oregon[i]. Unlike existing fossils, the fangs were found to be preserved in situ, allowing for a more complete understanding of O. rastrosus’ external appearance.

Unfortunately for sabre-toothed salmon stans, the position of the fangs did not support the previous diagnosis of them being used as sabre-teeth. Instead of facing downwards in the jaw, the fangs were found to protrude outwards from the premaxilla, making them more akin to facial tusks than any form of tooth. This positioning means the salmon did not use them to bite into potential prey, with the authors instead proposing they be used for defense, sexual display, intraspecific combat, or to construct nests in riverbeds[ii]. With this discovery, the title of sabre-toothed salmon became obsolete; in its place, the “spike-toothed” salmon has emerged.

Presently, it seems as though the tusks of O. rastrosus were used primarily for defense. In their study, Claeson et al. found that both males and females possessed similar tusks, meaning they likely did not function in a sociosexual capacity. It is possible they used the tusks to dig nests to lay their eggs like modern salmon, but when you consider that salmon can do this without such costly structures, it becomes less likely. With these possibilities eliminated, use as a defensive structure becomes more logical.

When you consider the known diet of O. rastrosus, the lateral positioning of the fangs – sorry, tusks, force of habit – begins to make sense. O. rastrosus are close relatives to O. nerka, the Sockeye Salmon, which feed on plankton as adults. To do so, Sockeye Salmon rely on gill rakers present on their branchial arches to filter plankton from surrounding waters. Fossils of adult O. rastrosus have been found with similar structures, which means they likely fed on plankton like their living cousins.

Given their filter-feeding diet, it makes little sense for O. rastrosus to require sabre-teeth. After all, it’s not like they would have been using them to catch prey! Instead, a lateral-facing defensive mechanism would have been more beneficial. Given its massive size, it’s likely that the spike-toothed salmon would have been a frequent prey item of some formidable predators. For protection, O. rastrosus may have developed the necessary hardware to combat whatever predators they would have faced in their coastal Pacific habitats.

Even if the sabre-toothed salmon no longer exists, it doesn’t take away from the legend of Oncorhynchus rastrosus. This was still the largest known salmonid in the fossil record, dwarfing the largest living salmonids by almost half a meter. Even if the tusks were positioned differently than previously considered, they still had an incredible appearance.

If the thought of a tusked salmon isn’t doing it for you, picture a giant zombie fish at the tail end of spawning, still alive but slowly withering away. Luckily you don’t have to, thanks to the talented work of Hodari Nundu. What a perfect piece to end a prehistoric obituary with!

Thank you for reading this article! April was a crazy moth for paleontology, which made the timing of my final exams for the winter semester very unfortunate. Now that they are done, I can’t wait to get back in the swing of things and recap all the events I missed!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come credit of the artists noted alongside each piece. Header image courtesy of Hodari Nundu.

References:

[i] Claeson, Kerin M., et al. “From Sabers to Spikes: A Newfangled Reconstruction of the Ancient, Giant, Sexually Dimorphic Pacific Salmon, †Oncorhynchus Rastrosus (SALMONINAE: SALMONINI).” PLOS ONE, edited by Paul Eckhard Witten, vol. 19, no. 4, Public Library of Science (PLoS), Apr. 2024, p. e0300252. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300252.

[ii] Black, Riley. “This 8-foot-long ‘Saber-toothed’ Salmon Wasn’t Quite What We Thought.” Animals, 24 Apr. 2024, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/saber-tooth-salmon-paleontology-reconstruction?loggedin=true&rnd=1714947392043.

13 replies on “An Obituary to the Saber-Toothed Salmon, 1972-2024”

Why don’t they call them the “tusked salmon?” That seems to be a better description of the fish, to me.

LikeLike

I’m not quite sure to be honest. I wholeheartedly agree – spike-toothed could mean anything, but tusked does give a much more accurate description. My best guess is they didn’t wanted to deviate too far from sabre-toothed salmon so they just swapped sabre with spike

LikeLike

or they’re not logical 🤣🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I can make my last statement because I am a scientist. And many of us are not logical at all I have found through the years.

LikeLike

In my experiences, it’s quite a fine line between being too logical and not logical enough

LikeLike

By the way, could you start including in your articles when animals lived?

LikeLike

Absolutely! Didn’t think it was too critical for the purposes of this specific article, but I will make sure to include that information in future articles.

For reference, the sabre/spike toothed salmon lived from the Miocene to Pliocene, 12-5 million years ago

LikeLike

Thanks! Your articles are always excellent. Both informative and entertaining. You’re a good writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I try my best, but sometimes the content writes itself – having said that, it’s nice to hear that I’m not butchering it!

LikeLike

Totally weird, but I can write comments to you but it won’t let me “like” your comments without getting a world press account. You think it would be the opposite.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, the liking and subscription options for non-Wordpress accounts can be a bit faulty…

LikeLike

You’re very far from butchering it. I like dates for things. It just gives me an idea of what/who was alive when etc. It puts things in a perspective timeline for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] There is no reason to believe that their extinct relatives, including the giant spike-toothed (née sabertoothed) salmon Oncorhynchus rastrosus. What I love about Hodari’s piece is the murky colour of the water […]

LikeLike