It is common knowledge that Velociraptor wasn’t quite as big as presented in the Jurassic Park franchise. While still a formidable predator, the Mongolian theropod weighed no more than 20 kilograms (45 pounds) at absolute maximum, making it far more comparable in size to a turkey than the wolf-sized animals shown on screen.

This doesn’t mean that giant raptors didn’t exist, however. In fact, giant Deinonychosaurs – the “raptor” dinosaurs which comprised two major lineages, the Dromaeosaurids and Troodontids – appear multiple times in the fossil record during the Cretaceous Period. Gigantism evolved separately within the lineage on at least three occasions, resulting in numerous genera achieving sizes that matched or exceeded the J.P. Velociraptor. This article examines the history of these dinosaurs.

1969: The Beginnings of Large Raptors

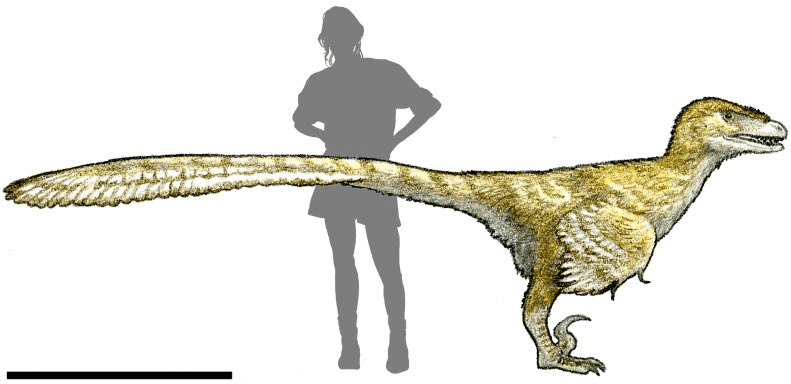

The first hints of giant Deinonychosaurs came with the description of the group’s namesake, Deinonychus antirrhopus, in 1969. Discovered five years prior in Montana by legendary American paleontologist John Ostrom, the visage of Deinonychus is what most people associate with raptor dinosaurs. Not only did Deinonychus possess all major traits of Dromaeosaurs (including long arms, an elongated tail with ossified tendons, full body feathers, and the infamous killing claw on the second digit of their feet), but the genus also served as the inspiration for Velociraptor in Jurassic Park[i]. Next time you’re watching a Jurassic Park film, just remember that the raptors are Velociraptor in name alone; in spirit, they are unequivocally Deinonychus.

Part of why Deinonychus was used to model the J.P. Velociraptors was due to its size. With average adult specimens reaching over 3 meters in length and weighing anywhere between 60-75 kilograms (130-165 pounds), Deinonychus was comparable in size to modern wolves[ii]. Some exceptionally large specimens have been estimated to weigh over 100 kg (220 lb), putting these individuals more in line with some small bears than any canine.

Aiding to the comparison with modern wolves is the long-held view that Deinonychus hunted in packs, a theory that is supported by the existence of two Deinonychus bonebeds discovered alongside the skeleton of the herbivorous Tenontosaurus[iii]. Whether these sites represent cooperative predation or a scavenging event following the death of the larger herbivore is debated, but one thing is for certain: a lone Deinonychus still would have packed quite the punch!

1993: A New Contender Emerges…

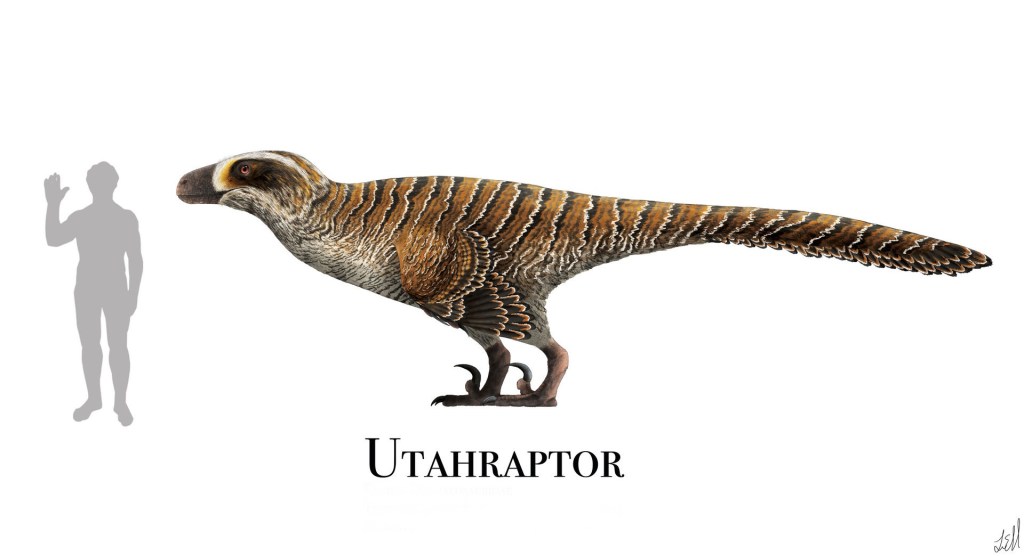

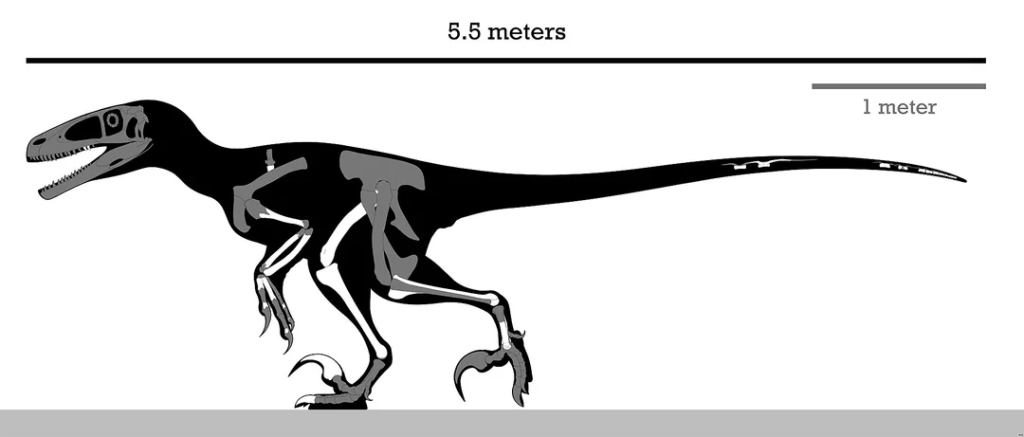

Following the discovery of Deinonychus, it wouldn’t be until after Jurassic Park’s theatrical release in 1993 that the next Giant Dromaeosaur emerged. Named after the American state in which it was discovered, Utahraptor ostrommaysi has long been considered the largest known raptor. Fossils of this stocky, heavily built Dromaeosaur from the Early Cretaceous Period (~135 million years ago) range from 4.8-6 meters long and have been hypothesized to weigh somewhere between 250-300 kg (550-650 lb). If Deinonychus was the wolf of the raptor family, Utahraptor was the tiger; a massive, powerful ambush predator that could dispatch larger prey some 20 million years before the appearance of its slimmer cousin.

Like Deinonychus, some debate exists as to whether Utahraptor hunted in packs. Almost 20 years ago, Utah state paleontologist Jim Kirkland and his team discovered a massive 9-tonne block of Utahraptor fossils on the side of a mountain. While preparation on the “Utahraptor Megablock” continues, paleontologists know the site contains at least 9 individuals, the majority of which are juveniles or subadults. Early returns from the site indicate that it was likely a predator trap, meaning the Utahraptor got trapped in some form of sediment after approaching a stuck herbivore. It is probable that the raptors did not live together and instead joined together for the chance at a free meal. Good news for the herbivores of North America, I suppose!

1999 & 2008: Intercontinental Giants

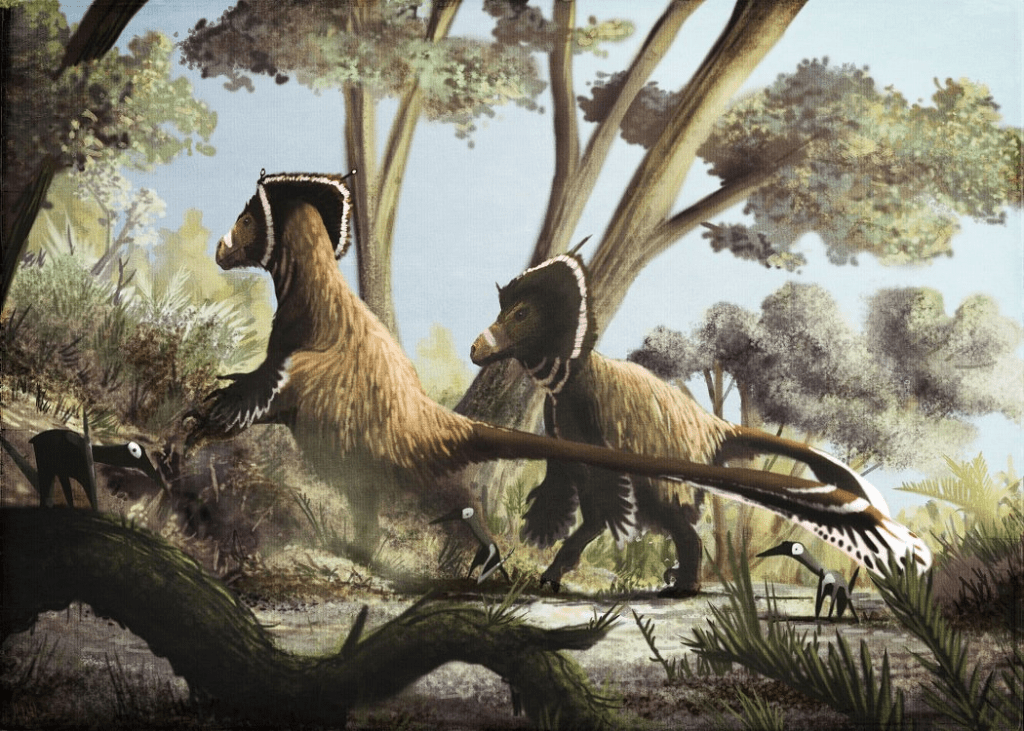

The next giant Dromaeosaurid was discovered before Utahraptor but would not be described until 1999. Long heralded as Utahraptor’s sister taxon, the robust skeleton of Achillobator giganticus is indeed very similar to its close relative. The major differences separating the two taxa? Time, location, and size. While Utahraptor lived in the Early Cretaceous of Utah, some 135 million years ago, Achillobator lived in the Bayan Shireh Formation of southeastern Mongolia during the early-Late Cretaceous, somewhere between 95-89 million years ago. On top of this, Achillobator was also smaller than its North American relative; with estimates ranging between 4-5 meters long and 165-250 kg (365-550 lb), it seems that Utahraptor had the edge on size.

For now, at least. Achillobator is known from less and more fragmentary remains than Utahraptor, which means additional discoveries could push Achillobator into contention with its more famous cousin.

Being smaller than Utahraptor shouldn’t take away from the fact that Achillobator was still massive. Aided by the extinction of the Carcharodontosaurids, Achillobator would have played the role of top predator in Bayan Shireh, terrorizing local fauna which included numerous Ankylosaurs, Hadrosaurs, Ornithomimids, and Therizinosaurus. While some Tyrannosaurids were present, they had not yet achieved the gigantism observed a mere 10 million years later. In the absence of giant contemporary theropods, the Dromaeosaur transitioned into the role of top predator – a recurring theme in their evolution, given that Utahraptor also appears to have lived in ecosystems devoid of any other large theropods.

This is true for the next Deinonychosaur as well, the Argentinian genus Austroraptor cabazai. Described in 2008, Austroraptor is comparable to Utahraptor in length, with estimates ranging between 5-6.2 meters[iv]. The length of the two genera is where the comparison ends, as the two raptors had vastly different morphologies and ecological roles. While Utahraptor was a bulky ambush predator, Austroraptor was slenderer and adapted to hunting fish. Though some weight estimates place Austroraptor at approximately 340 kg (750 lb), I would imagine it to be more in the ballpark of Utahraptor. With an elongated snout and conical teeth found throughout its jaws, there is little doubt that Austroraptor was well equipped for plucking fish out of the waterways of Maastrichtian South America, some 70 million years ago.

Austroraptor is the most famous member of Unenlagiinae, a family of Dromaeosaurids known only from fossils in the southern hemisphere. Like Austroraptor, most Unenlagiines possessed elongated snouts, but also differed from their northern counterparts in the anatomy of their tail vertebrae, hips, and ankles. It is currently unknown when Unenlagiinae and the subfamily of Dromaeosaurids that contains Deinonychus, Utahraptor, and Achillobator – known as Eudromaeosauria – diverged, but it likely occurred in the Cretaceous prior to the appearance of the dinosaurs featured in this article[v]. This indicates that gigantism evolved in the two lineages separately, resulting in vastly different fauna separated by continents and millions of years in evolutionary history.

2015: The Chimera from Hells Creek

The last of our giant Dromaeosaurids is the most controversial. At this time, paleontologists aren’t quite sure how big it is, whether it should be a Eudromaeosaur or a Unenlagiine, or if it even exists. Dakotaraptor steini is truly an enigma, and one that may not be solved anytime soon.

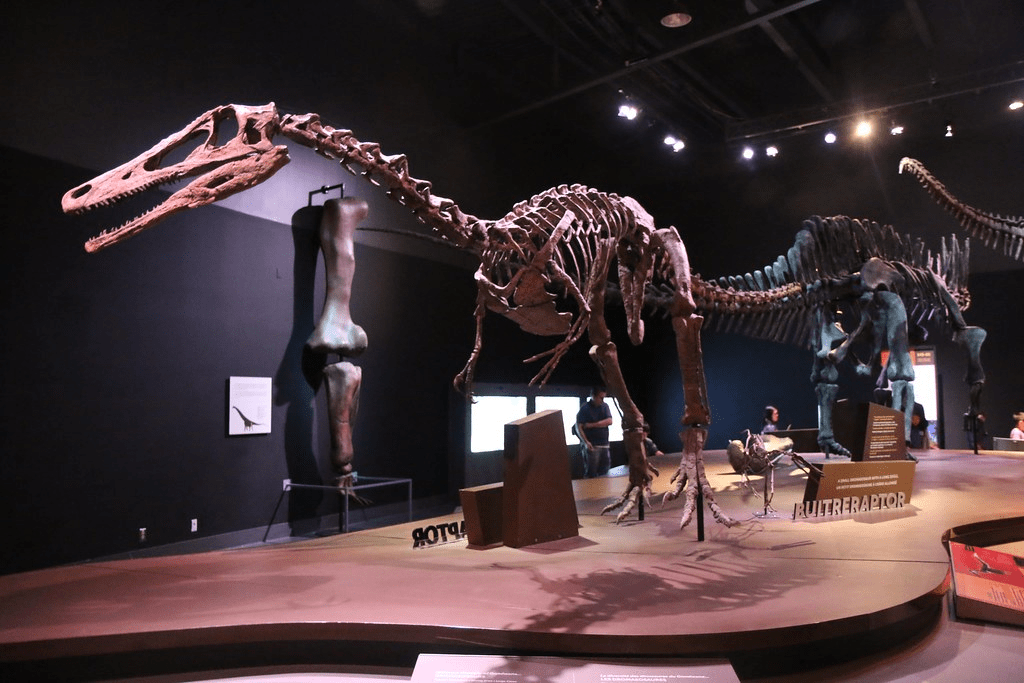

In 2015, paleontologist Robert DePalma described a massive raptor found in the Late Cretaceous (66 million years ago) Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota, USA. When Dakotaraptor was first described, the holotype specimen consisted of teeth, a furcula (or wishbone), some elements from the fore-and-hindlimbs, and several tail vertebrae. At the time, estimates of 6 meters long and 350 kilograms (770 pounds) were floated around[vi]. Not only was this the largest raptor known to science, but Dakotaraptor also represented a long-sought after mid-sized predator that lived alongside Tyrannosaurus rex in Hell Creek ecosystems.

Less than a year later, cracks began to form in Dakotaraptor’s foundation. Fossils thought to be its furcula were identified as belonging to a prehistoric turtle, removing some of the known fossil material attributable to Dakotaraptor. In 2023, theropod paleontologist Andrea Cau took this a step further, declaring that Dakotaraptor did not exist. Instead, Cau asserted that Dakotaraptor was a chimera of other theropods; parts of the tail vertebrae likely belonged to Ornithomimids, elements from the limbs were hypothesized to belong to Oviraptorids, and the claws belonged to Therizinosaurs[vii]. For many in the field, it felt like a death knell for the Hell Creek raptor.

It should be noted Cau’s hypothesis was released in a blog post on his website, not a reviewed research article. If Cau had access to the specimen to perform his study, it could have resulted in a scientific publication; unfortunately, Robert DePalma has not yet made the specimen accessible. In fact, nobody is sure where the fossils of Dakotaraptor are – or why they are hidden. It doesn’t help DePalma’s case that he has been found guilty of committing academic misconduct with his research practises, making the situation all the more tenable.

Regardless, I would say that Dakotaraptor is still valid. Not every fossil attributable to the genus was dismissed by Cau, meaning that a large raptor likely did exist in Hell Creek. To what extent remains uncertain, but it seems as though giant raptors were present at the end-Cretaceous of North America – for now, at least.

Well, that concludes the list of giant Deinonychosaurs in the fossil record! Thank you for reading this artic-

Wait a second. I’m forgetting something, aren’t I?

Ah yes, the mystery taxa. While the five genera listed above represent the named examples of gigantism in Deinonychosauria, there are three other potential cases that are worth noting.

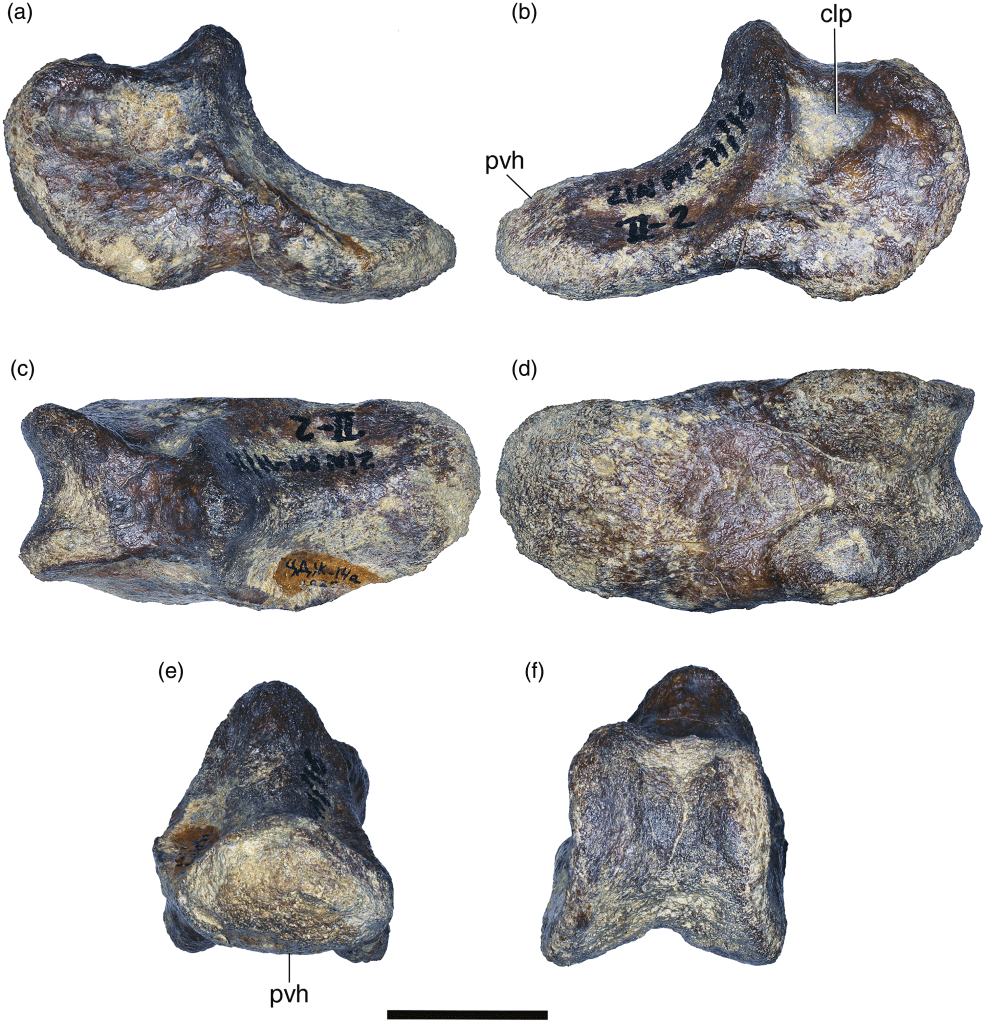

If you were to ask die-hard paleonerds what the largest Dromaeosaurid is, they may respond with the Bissekty Giant. Named after the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan in which it was discovered, little is known about this enigmatic giant. As it stands, the only material known from this dinosaur is a single pedal phalanx[viii].

You read that right: a single toe bone.

Now, this bone is extremely large. Some estimates of the Bissekty Giant indicate that it could reach almost a metric tonne (1,000 kg/2,200 lb) in weight, tripling even the heaviest Utahraptor and Austroraptor. As tempting it would be to hype up the Bissekty Giant – as some people in the paleo community have done – it’s important to show restraint for sensationalism. It is entirely possible that a massive, Tyrannosaur-sized raptor did call Uzbekistan home during the Cretaceous. But I am old enough to remember when Megaraptor and kin were considered the largest Dromaeosaurids; now, they are Tyrannosauroids. Time will tell if the Bissekty Giant is truly the world’s largest Dromaeosaur, but for now, I hesitate to grant it that title.

The other Deinonychosaurs: Enter the Troodontids

Speaking of older paleontology, who here remembers Planet Dinosaur? A six-part BBC series released in 2011, Planet Dinosaur was the BBC’s return to dinosaurs following the success of Walking with Dinosaurs in 1999. Though many segments were featured, one of the most interesting took place in the Prince Creek Formation of northern Alaska. It was here that audiences were introduced to the Alaskan Troodon, a potential sub-species of Troodon far more massive than it’s more southern relatives.

Like the Bissekty Giant, the Alaskan Troodon is only known from partial remains. Instead of a toe bone, it is the teeth of Troodon which represent the gigantic fauna, though in far larger quantities than the single bone attributable to the Uzbek dinosaur. These teeth are double the size of Troodon specimens found in Montana, suggesting that the brainy dinosaur may have been better-suited for the long polar nights of late-Cretaceous Alaska than the more continental conditions found elsewhere[ix].

There are some issues with declaring the Alaskan Troodon to be a giant Dromaeosaur, however. Like the Bissekty Giant, establishing size from partial remains is almost impossible, making any estimates extremely flawed. If we simply double the size of Montana Troodon, we only get an animal that is somewhere in the range of 70 kg (150 lb) at maximum, making it around the size of your average Deinonychus. Plus, research on dental enamel has found that the Alaskan Troodon didn’t differ from their southern counterparts in diet, meaning they likely didn’t occupy a different ecological niche than their contemporaries.

The final giant raptor is also the newest. In April 2024, researchers led by Lida Xing working out of the Longxiang locality in China described a set of footprints belonging to a massive Deinonychosaur[x]. The shape of the footprints, which reached a maximum size of 36 centimeters, indicated that they likely belonged to a Troodontid. The size of the ichnotaxon (or species of fossil footprint), named Fujianipus yingliangi, suggest that the animal who produced them would have been close to 2 meters tall at the hips – about the same height as Utahraptor, Austroraptor and other giant Deinonychosaurs. While “giant” Troodontids had been found before, Fujianipus is the first that exceeded 100 kilograms in weight, bringing the total number of Deinonychosaur lineages to exceed such threshold to three.

Now, if only a body fossil of a Troodontid could be found!

In total, five different genera and three additional specimens comprise our knowledge of giant Deinonychosaurs. Though the Bissekty Giant may be the unofficial largest raptor, the current *undisputed* record holders are Utahraptor and Austroraptor. Given that two of these giants have been published in the last 2 years, I imagine that plenty of other large raptors are just waiting to be discovered…

When they do, I’m sure that I’ll be here to report about them. At the very, I’ll remind news outlets that you don’t have to mention Jurassic Park when talking about giant raptors!

A bit hypocritical, I know!.

Thank you for reading this article! Did you know that the description of Utahraptor was published a mere week after the premier of Jurassic Park? If only Jurassic Park had come out just a little bit later, and we might never have to hear about how inaccurate their raptors are! Except for their feathers and wrists, of course…

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the sources and illustrators noted under each piece.

Header image courtesy of Melusine-Designs, taken at the Field Museum of Natural History.

[i] Black, Riley. “You Say ‘Velociraptor,’ I Say ‘Deinonychus.’” Smithsonian Magazine, 16 Nov. 2013, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/you-say-velociraptor-i-say-deinonychus-33789870.

[ii] Molina-Pérez, Rubén, et al. Dinosaur Facts and Figures. Princeton University Press, 2019.

[iii] Maxwell, W. Desmond, and John H. Ostrom. “Taphonomy and Paleobiological Implications ofTenontosaurus-Deinonychusassociations.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 15, no. 4, Informa UK Limited, Dec. 1995, pp. 707–12. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1995.10011256.

[iv] Molina-Pérez, Rubén, et al. Dinosaur Facts and Figures. Princeton University Press, 2019.

[v] Cau, Andrea, et al. “Synchrotron Scanning Reveals Amphibious Ecomorphology in a New Clade of Bird-like Dinosaurs.” Nature, vol. 552, no. 7685, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Dec. 2017, pp. 395–99. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24679.

[vi] Paul, Gregory S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton UP, 2016, books.google.ie/books?id=PFuzDAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=princeton+field+guide+to+dinosaurs&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api.

[vii] Dakotaraptor Non Esiste [AGGIORNAMENTO]. theropoda.blogspot.com/2023/09/dakotaraptor-non-esiste.html?fbclid=IwAR2GlY5b06xSVIGDgzKM9RVqMeey2xPIaXyuW2QAwiq9s97a0qPOiv3A38E&m=1.

[viii] Sues, Hans-Dieter, et al. “A Giant Dromaeosaurid Theropod From the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian) Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan and the Status of Ulughbegsaurus Uzbekistanensis.” Geological Magazine, vol. 160, no. 2, Cambridge UP (CUP), Dec. 2022, pp. 355–60. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0016756822000954.

[ix] Fiorillo, A. R. “On The Occurrence of Exceptionally Large Teeth of Troodon (Dinosauria: Saurischia) From the Late Cretaceous of Northern Alaska.” PALAIOS, vol. 23, no. 5, Society for Sedimentary Geology, May 2008, pp. 322–28. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2007.p07-036r.

[x] Xing, Lida, et al. “Deinonychosaur Trackways in Southeastern China Record a Possible Giant Troodontid.” iScience, Elsevier BV, Apr. 2024, p. 109598. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109598.

3 replies on “A History of Giant Raptors in the Fossil Record”

Very interesting. Like you I think that we need to be cautious when it comes to the Bissekty giant etc. and I also think that Dakotaraptor was likely valid and people shouldn’t just act like it’s not. An interesting article is this one that basically debunks the fact that Dakotaraptor is “only” made up of parts of other Dinosaurs: https://thesauropodomorphlair.wordpress.com/2019/09/28/nuking-anzuraptor/

I know it’s not by an actual Palaeontologist but it’s well researched and has good sources and evidence to support it. Either way I think there was definitely some sort of giant Dromaeosaur in Hell Creek.

LikeLike

Caution is always key in paleontology; chasing after headlines and sensationalism rarely works when there isn’t concrete evidence to support a claim! The big question I think now with Dakotaraptor now is discovering what kind of raptor it was; a bulky Eudromaeosaur like Utahraptor, or a giant fish-eater like Austroraptor? We know other South American fauna migrated to North America at the very end of the Cretaceous, so maybe the giant raptors were one such example..

It’s something I will await for!

LikeLike

[…] being featured in the series. It is unclear how reliable this information is, but given the public intrigue surrounding large raptors, I would imagine that WWD 2025 will introduce the audience to at least one such […]

LikeLike