A question I often see asked about dinosaurs is simple: were they good parents?

If the fossils of one duck-billed dinosaur are any indication, they absolutely were.

The year was 1978. For much of the prior decade, paleontologist David Trexler, his wife Laurie, and his mother Marion had spent long hours in the cliffsides of Montana, USA, looking for fossils to supply their local store, the Trex Agate Shop in Bynum. Montana is perhaps the best place in the United States to run such a business, as fossils of many Late Cretaceous dinosaurs – including those of Tyrannosaurus rex – are plentiful throughout the state.

Though a fateful expedition near the town of Choteau would not produce a T. rex, it did uncover the first traces of a far more important site.

As Marion wandered through the badlands of Montana, she soon located the tell-tale bones of a dinosaur. Though the tiny specimen didn’t immediately stand out from the landscape like the skull of a Triceratops would, Marion’s keen eyes noticed the small grey bones amongst the rocks. After consulting with David, the Agate team soon knew what they were dealing with: the skeleton of a baby Hadrosaur, or duck-billed dinosaur[i]. After removing the specimen from the field, the fossils were soon on display at the Trex Agate Shop. They would not be long for Bynum, however, as a visit from one of Montana’s most recognizable paleontologists resulted in a massive shift in our understanding of dinosaur behaviours.

John “Jack” Horner is many things. Famously, Horner was the key scientific advisor of the Jurassic Park films, but he was also the lead force behind the “Chickenosaurus” genetic project; the curator of the Museum of the Rockies until 2016; and now, a rather controversial figure in the field, both for his theories (such as T. rex being an exclusive scavenger) and for some of his extracurricular conduct. But in 1978, he was an up-and-coming paleontologist looking for a big break.

He would find this in the halls of the Trex Agate Shop. After noticing the baby hadrosaur on display, Horner connected with Marion to locate the site from which the specimen had originated. After being guided to the location, Horner and his research partner Bob Makela set out to uncover further remains of the individual or others from its genus. To say they succeeded would be an understatement, as Horner and Makela found something truly unprecedented: a massive colony of Hadrosaur nests.

While it started as a single nest with 16 baby dinosaurs, annual expeditions to the site over the next five years would uncover 14 bowl-shaped nests[ii]. Within each were the eggs and skeletons of young hadrosaurs, ranging from embryos to 1-meter-long babies[iii]. Some nests were found within several meters of each other on the same stratigraphic layer, indicating that they were laid by multiple reproducing adults simultaneously. The discovery of these nesting colonies gave strong support that the adult dinosaurs were practising complex social behaviours, living in herds that reared their offspring together.

In 1979, Horner and Makela published their preliminary findings of the site, opting to name the Hadrosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum – the “good mother lizard”. But was this name earned? The answer appears to be yes. Though no adults were found in the nests, later analyses of the baby dinosaurs found their bones to be weak and incapable of sustained locomotion[iv]. This, in addition to the presence of vegetation and sediments in the nests, has led paleontologists to theorize that the adults protected their young for at least the first few months of their lives, first incubating their eggs and later supplying food to aid the growth of their young.

When Horner and Makela announced their discovery in Nature, it set the paleontological community ablaze. While it may be well-known now that some dinosaurs practised parental behaviours, it was a complete novelty in 1979. The notion of a large, herbivorous dinosaur exhibiting parental behaviour would have shocked those acquainted with the notion of unintelligent, simple creatures. The discovery of Maiasaura, alongside the publication of the swift-footed Deinonychus (another Montana native!) almost a decade prior, went a long way in convincing the public that dinosaurs were more sophisticated animals than previously imagined.

It should be noted that we don’t know if the mother or father was responsible for raising the young. Bird parents typically share responsibilities, and while parenting in most Crocodiles rests in the hands of protective mothers, some species rely solely on the fathers. As it stands, we may never know if Maiasaura truly was the good mother lizard. However, since no evidence exists to work against this claim, I see no issue with the name – for now, at least!

The Legend of Egg Mountain

Maiasaura wasn’t the only dinosaur raising their young at the site near Choteau, the aptly named Egg Mountain. Excavations at Egg Mountain during the 1980s would uncover the nest of a completely different dinosaur, the possibly omnivorous Troodon. Once thought to belong to the herbivorous Orodromeus, later analysis of the eggs found that the embryos within clearly belonged to the nimble-footed theropod[v].

The nests of Troodon differ from those of Maiasaura in several aspects. Given that Maiasaura adults weighed between 3-5 tonnes, they were incapable of brooding their eggs for fear of crushing them, instead applying vegetation and sediment to warm and brood the embryo within. Troodon, a dinosaur that weighed no more than 50 kilograms at absolute maximum, had no such issue, instead resting on top of their eggs to incubate them. The egg shape is also quite different, with those of Maiasaura being more circular than the elongated oval-shaped eggs of Troodon.

Though Maiasaura is known to have laid anywhere between 20 and 40 eggs, the clutch size of Troodon has been debated. Nests containing up to 24 eggs positioned in pairs have been discovered, but a recent study has suggested that Troodon could only lay 4-6 eggs due to their metabolic inability to form eggshells quickly[vi]. If this is the case, it would imply that Troodon participated in a strange kind of communal nesting in which multiple mothers laid their eggs in a single nest. While this may seem strange, it almost reflects the male-reliant parenting strategy of the modern Emu, in which males are left to incubate and raise the eggs by themselves. Perhaps Troodon utilized a similar strategy, in which males reproduced with multiple females and were then left to raise the children. If true, both Maiasaura and Troodon would have employed strategies of communal nesting – albeit very different ones.

Is it too late to rename Troodon the good father lizard? Patersaurus, perhaps?

A Complete Series, From Birth to Death

In the years following Horner’s excavations, Maiasaura has become one of the most common dinosaurs in the fossil record. The specimens at Egg Mountain, combined with more adult-populated Maiasaura bonebeds that confirmed herding behaviours in the genus, have resulted in the discovery of more than 200 specimens. This has allowed paleontologists to study all stages of Maiasaura growth, an opportunity not afforded for most prehistoric genera.

From the moment they hatched, Maiasaura began to grow exponentially. Within weeks, the tiny babies would have grown to well over a meter long, allowing them to leave the nest and forage for themselves. This period would have been extremely dangerous for the young dinosaurs, as their proximity to large adults would have attracted plenty of large predators in addition to the plentiful hardships that young animals face. Some studies have estimated that almost 90% of baby Maiasaura would not have survived past their first year, an unfortunate reality for the small dinosaurs[vii].

From here, the Maiasaura would have continued to grow rapidly for several years until the age of 8, at which point they reached full skeletal maturity. Major changes occurred throughout their body during this period, especially in the hips and legs which became more robust to accommodate the dinosaurs’ increased body weight[viii]. When it was all said and done, the Maiasaura had grown from 30-centimetre-long hatchlings to 7-9-meter-long adults within a mere 8 years. If you thought you had an immense growth spurt in your teen years, you may need to reconsider!

Fatherhood for the Good Mother Lizard

In many ways, Maiasaura is very typical for a Hadrosaur. Like other Hadrosaurs, Maiasaura had a complex dental battery that featured thousands of constantly replacing teeth designed for crushing and processing plant matter. Though capable of running on two legs, the majority of Maiasaura’s adult life would have been spent on all fours. No obvious defensive structures were present, but their sheer size, muscular limbs and tails, and herding behaviours likely deterred most predators from attacking.

One key distinguishing feature of Maiasaura is a small crest located on top of their orbits. It may not be as memorable as those of other Hadrosaurs, but it still would have been useful as a sociosexual feature for display or to combat other Maiasaura. In life, it may have been enlarged by a keratinous extension, turning it from a relatively muted feature into a far more prominent structure.

Some have speculated that males used their crests to joust for the right to mate with females[ix]. There is evidence that Maiasaura was sexually dimorphic (one sex is bigger than the other), with one group of Maiasaura fossils being 45% larger than the other[x]. While these two facts make it seem as though the larger males competed for females, it is currently unknown which sex was bigger. Female Maiasaura may have dwarfed their male counterparts, a reality that would have been fitting for the matriarchal dinosaur. Additionally, all Maiasaura fossils possess a bony structure, meaning both males and females had some form of crest. Males may have had a more colourful or pronounced structure, but no evidence exists to currently support this hypothesis.

For now, we can assume that males did use their crests for display – but it is unclear if they were short kings, or lovable giants.

Life at Two Medicine

Maiasaura fossils are primarily from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, though some specimens have been discovered in the Oldman Formation of southern Alberta, Canada[xi]. The discovery of Maiasaura in the late 1970s sparked a new wave of interest in Two Medicine, diverting paleontologists from the nearby Cloverly and Hell Creek Formations to the largely unexplored site.

The rocks of the Two Medicine Formation date back to the Late Cretaceous Period, spanning between 83-74 million years ago. At this time, North America was divided into two separate land masses – Laramidia to the west, and Appalachia to the east – by a vast inland seaway. Located inland on Laramidia, Two Medicine was a warm, semiarid landscape that experienced high seasonality, with large rivers dotting the landscape.

Maiasaura fossils hail from the upper Two Medicine, dating to approximately 76 million years ago. At this time, Maiasaura was the largest and most populous herbivore in the region; only the Lambeosaurine Hadrosaur Hypacrosaurus is known to have coexisted with Maiasaura. Alongside these duckbills was the small ornithopod Orodromeus, a lightning-quick herbivore no larger than a cat. Though some documentaries, such as Dinosaur Planet, have featured Maiasaura living alongside the Ceratopsian Einiosaurus, no evidence exists to support their coexistence in Two Medicine.

Predators were abundant too, and none were more terrifying than the Tyrannosaurids. At Two Medicine, two genera were present: the lithe Gorgosaurus, and the bulky, potentially pack-hunting Daspletosaurus. Daspletosaurus is known to have coexisted with Maiasaura, with teeth of the formidable carnivore being found in the area around Egg Mountain[xii]. No interactions between predator and prey have currently been documented, but there is little doubt that Daspletosaurus would have represented a formidable threat to the Hadrosaur.

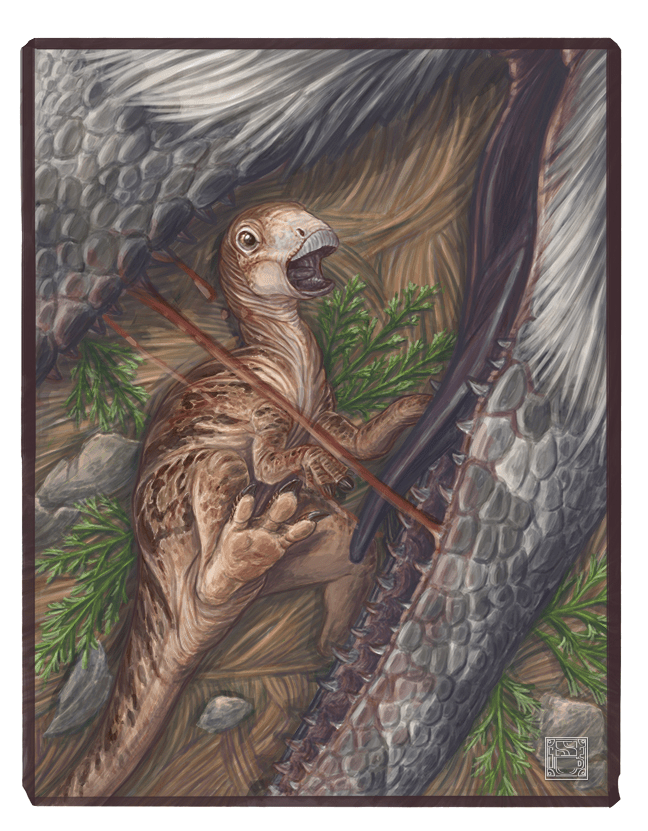

Other animals known to coexist with Maiasaura include Troodon, its close relative (and maybe synonym) Stenonychosaurus, and the tiny Dromaeosaurid Bambiraptor. Though too small to bother the adult Maiasaura, these sickle-clawed predators may have posed a threat to the vulnerable hatchlings. You can’t have a 90% mortality rate as an infant without at least some predators around!

To Conclude…

Since Maiasaura fossils are so common, there are several museums in which you can see their fossils. In the United States, specimens of Maiasaura can be found on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois; the Museum of the Rockies, the Old Trail Dinosaur Museum, and the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center in Montana; and the Center for Science, Teaching, and Learning in Rockville, New York. Other specimens can be found at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, and at the Brussels Natural History Museum in Belgium.

In 1985, Maiasara’s importance to paleontology was recognized when it was named the official state fossil of Montana. This designation is very impressive, even more so when you consider that Montana is the unofficial home of T. rex. Finally, the Hadrosaur gets the upper hand!

Maiasaura will always be remembered as the dinosaur that helped to change the public’s perception of dinosaurs. At a time when fossils of young dinosaurs were exceedingly rare, entire droves of baby Maiasaura emerged, providing an intimate view of young dinosaurs and the role their parents played in their upbringing. Though other dinosaur nesting colonies would be discovered in the years to come, the good mother lizard and her kin will forever be enshrined as the first known parenting dinosaur.

Happy Mother’s Day, everyone!

Whether it’s in the depths of prehistory or the present day, mothers have always been there to support us. Without my mother, this website wouldn’t be where it is today; from the beginning, she encouraged me to pursue my passions and start this website over 12 years ago. Thank you, Mom!

My grandmother’s influence was also fundamental in my love for paleontology. Whether it be the trips to the Royal Ontario Museum or fossil hunting in the Humber River, my Oma helped put me on the path I find myself on today. For that, I will be forever grateful!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images belong to the illustrators or sources accompanying each image.

Header image courtesy of Joschua Knüppe, whose work can be found at his twitter here.

Works Cited:

[i] Tribune, Kristen Inbody Great Falls. “Marking 40 Years Since Tiny Bones Changed the World’s Understanding of Dinosaurs.” Great Falls Tribune, 3 July 2018, http://www.greatfallstribune.com/story/news/2018/07/02/marking-40-years-since-tiny-bones-changed-worlds-understanding-dinosaurs-egg-mountain-trexler-bynum/751412002.

[ii] Freimuth, Willie. “Paleontology – Egg Mountain.” Augusta Choteau, 2024, serc.carleton.edu/research_education/mt_geoheritage/sites/augusta_choteau/paleontology.html.

[iii] Brusatte, Stephen L. Dinosaur Paleobiology. John Wiley and Sons, 2012.

[iv] Brusatte, Stephen L. Dinosaur Paleobiology. John Wiley and Sons, 2012.

[v] Varricchio, David J., et al. “Embryos and Eggs for the Cretaceous Theropod Dinosaur Troodon Formosus.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 22, no. 3, Informa UK Limited, Sept. 2002, pp. 564–76. Crossref, dx.doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0564:eaeftc]2.0.co;2.

[vi] Tagliavento, Mattia, et al. “Evidence for Heterothermic Endothermy and Reptile-like Eggshell Mineralization inTroodon, a Non-avian Maniraptoran Theropod.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 15, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Apr. 2023. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2213987120.

[vii] Woodward, Holly N., et al. “Maiasaura, a Model Organism for Extinct Vertebrate Population Biology: A Large Sample Statistical Assessment of Growth Dynamics and Survivorship.” Paleobiology, vol. 41, no. 4, Cambridge UP (CUP), Sept. 2015, pp. 503–27. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2015.19.

[viii] Eberth, David A., et al. Hadrosaurs. Life of the Past, 2014.

[ix] Benton, Michael J. Dinosaurs Rediscovered. Thames and Hudson, 2019.

[x] Benton, Michael J. Dinosaur Behavior. Princeton UP, 2023/

[xi] McFeeters, Bradley D., et al. “First Occurrence of Maiasaura (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) From the Upper Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Southern Alberta, Canada.” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, vol. 58, no. 3, Canadian Science Publishing, Mar. 2021, pp. 286–96. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjes-2019-0207.

[xii] Freimuth, Willie. “Paleontology – Egg Mountain.” Augusta Choteau, 2024, serc.carleton.edu/research_education/mt_geoheritage/sites/augusta_choteau/paleontology.html.