For some time, it has been believed that the remains of long extinct helped inspire myths from across the world. However, actual evidence of interaction between past societies and fossils is exceedingly rare.

So, when a paper claiming to connect abundant South African fossils to a piece of cave art is published, people take notice.

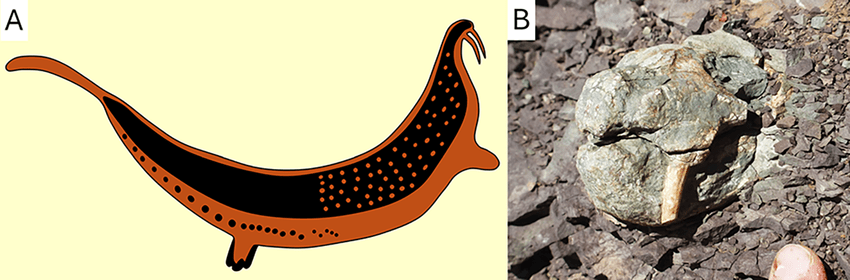

On September 18th, paleontologist Julien Benoit published an article in PLos ONE describing a mysterious cave painting from the La Belle France farm in Free State, South Africa. Known to locals as the “Horned Serpent” panel, the painting was created by the San people sometime between 1821 and 1835 based on contextual evidence from the warriors depicted in the piece[i]. Within the panel is a long, worm shaped animal with brown flanks and a black middle. The animal appears to have a long, tapered tail, stumpy legs, and a set of downward-facing tusks. It is the presence of these tusks that has made identification of the Horned Serpent difficult for anthropologists and amateur sleuths alike, as no living South African animal in the region has similar features.

In his article, Benoit argues that the Horned Serpent was inspired by the remains of Dicynodonts from the Karoo Basin of South Africa[ii]. Fossils of Dicynodonts, a family of therapsids (or mammal cousins) from the Late Permian and Triassic periods, are exceedingly abundant in the region and possess a pair of enlarged tusks protruding downwards from their upper jaws. Sound familiar? Some of these specimens are even of exceeding quality; in 2022, two mummified skeletons of the Dicynodont Lystrosaurus were found within the rocks of the Karoo. In fact, outcrops which contain Lystrosaurus fossils are mentioned as being found within 10 kilometers of La Belle France, meaning it is possible that the San people encountered these remains.

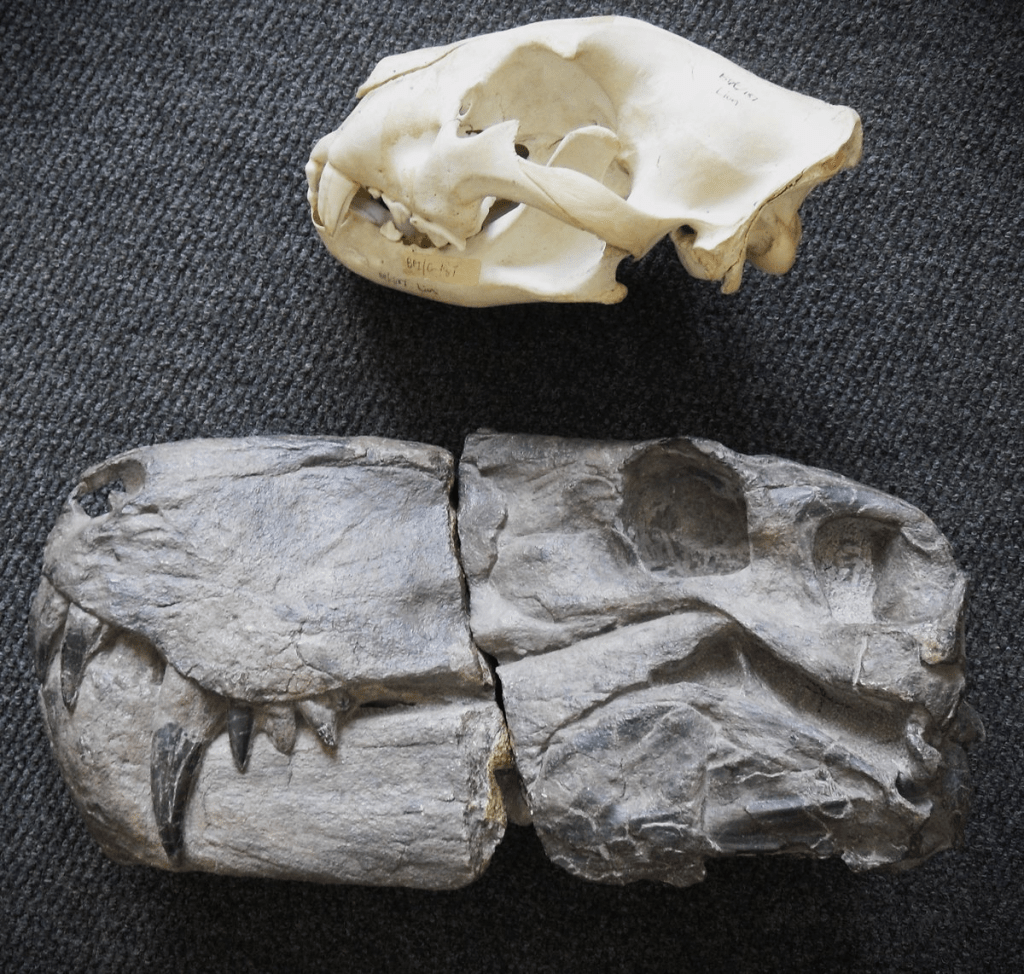

Could the Horned Serpent have been inspired by Dicynodonts? I remain skeptical. If we look beyond their dental configuration, we can see that the post-crania of Dicynodonts are rather unsimilar to the tusked animal seen in the panel. By comparing Lystrosaurus skeletal material with the Serpent, we can see vast differences in the length of their mid-sections, legs, and tail. The tail is especially noteworthy in my opinion. Dicynodonts almost universally have small, stump-like tails that contrasts the long appendage seen at La Belle France. While Benoit uses taphonomy biases to explain the short legs of the creature, I highly doubt these processes would add material to their tails.

Another issue I have with the connection to Dicynodonts is the size of the animal. When scaling to the antelope illustrated on top of the Serpent, we can tell that the animal is massive. Most Dicynodonts from the Karoo are not quite so large, with genera like Lystrosaurus only reaching a meter long at absolute maximum. Having said this, fossils of Kannemeyeria – the largest South African genus of Dicynodont – are present and relatively common in the Karoo. Yet the same anatomical issues present with comparing the serpent to Lystrosaurus persist with Kannemeyeria. These issues may even be magnified, if you consider that the tiny skull of the Horned Serpent is supposed to have been inspired by the hulking skull of Kannemeyeria. Overall, not a great fit!

If not inspired by Dicynodonts, then what inspired the Serpent? At first glance, I thought it superficially resembled a skink, a living order of lizards with stumpy legs and long tails that are found throughout South Africa. Benoit clearly made this association too, as he makes a compelling argument against this possibility by detailing how lizards are portrayed much differently in San artwork.

Compelling enough, but what about a Walrus? Benoit’s introduction describes the Serpent as a “walrus-like figure,” after all; could this have been the source of inspiration?

I believe this is highly improbable. Walruses primarily live in the very cold waters of the Arctic Ocean in places like Canada and Russia – the opposite side of Earth as South Africa. While some stray migrations have been documented on occasion[iii], it is unlikely that one would make it all the way to South Africa. And while European settlers had begun to colonize South Africa by the time of La Belle France’s illustration, the first colonizers from England consisted mostly of families who were struggling to meet basic needs. They were unlikely to have ever encountered a Walrus, let alone conquer the almost impossible logistics needed to get its carcass to South Africa in 1821. Thus, I think it’s fair to take Walruses off the suspect list.

While I think we can eliminate the Walrus, other pinnipeds should not be discounted. Fur Seals are common on the southern coast of South Africa and possess the same body shape as the horned serpent. The tusks of the epitaph could represent a fish or piece of aquatic vegetation that has become wrapped around its neck. The size of the Serpent is more problematic, given that Fur Seals aren’t notably large animals. However, two massive pinnipeds – Leopard Seals and Southern Elephant Seals – have been documented getting lost and ending up on the South African coastline on occasion[iv]. Both species dwarf the native Fur Seals; female Leopard Seals can weigh over half a tonne[v], while male Southern Elephant Seals can weigh over 4 tonnes[vi]. Now that sure seems to be within the size range of the Serpent! Male elephant seals even have a bulbous nose that could be misinterpreted from afar as a tiny head, making them an ideal candidate for the Serpent’s inspiration.

Of course, there is no way to definitively prove that the Horned Serpent was inspired by an Elephant Seal. The easiest way to confirm the identity of the Horned Serpent – fossil or not – would be to find proof of either Seal or Dicynodont bones inside La Belle France. Sadly, such proof does not exist. Benoit does note, however, that the San may have had experience with fossils and possessed knowledge that prehistoric species existed. While digging into the former reveals this is speculation without practical evidence[vii], it is likely that the San – an ancient people who inhabited southern Africa for well over 100,000 years[viii] – were aware that giant animals once present in the region through oral history. It is possible that the Horned Serpent could have been inspired by tales of these long-extinct animals, but without direct confirmation, this remains speculation.

Not that this speculation is bad, per se. Connecting paleontology with anthropology is one of my favourite niche research topics and one that I’d love to see explored further.

One final concluding thought: why were Gorgonopsids not considered potential candidates for the Horned Serpent? Not only do they have massive canine teeth (which could be misinterpreted as tusks), but their body is much more like the Horned Serpent. Their fossils are common in the Karoo too; perhaps not to the degree of the Dicynodonts, but numerous genera larger than 3.5 meters have been found in South Africa. Wouldn’t it have made more sense that the 40-centimeter skulls of genera like Inostrancevia, Rubidgea, and Dinogorgon be more likely candidates for the inspiration of the Horned Serpent?

Perhaps not. But I sure think so!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the artists and sources noted alongside each image.

[i] Benoit, Julien. “A possible later stone age painting of a dicynodont (Synapsida) from the South African Karoo.” PLoS ONE, vol. 19, no. 9, Sept. 2024, p. e0309908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309908.

[ii] Benoit, Julien. “A possible later stone age painting of a dicynodont (Synapsida) from the South African Karoo.” PLoS ONE, vol. 19, no. 9, Sept. 2024, p. e0309908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309908.

[iii] COSEWIC. COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. report, 2006, http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_atlantic_walrus_e.pdf.

[iv] “Two Oceans Aquarium | Two oceans aquarium tags kommetjie’s visiting….” Two Oceans Aquarium, 1 Nov. 2022, http://www.aquarium.co.za/news/two-oceans-aquarium-tags-kommetjies-visiting-leopard-seal#:~:text=Although%20young%20leopard%20seals%20sometimes,been%20spotted%20in%20our%20waters.

[v] “The Antarctic Sun: News about Antarctica – Female leopard seals are way, way bigger than their male counterparts.” Public Domain, antarcticsun.usap.gov/science/4736.

[vi] “—.” Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, http://www.asoc.org/learn/southern-elephant-seals.

[vii] Helm, Charles W., et al. “Interest in geological and palaeontological curiosities by southern African non-western societies: A review and perspectives for future study.” Proceedings of the Geologists Association, vol. 130, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 541–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2019.01.001.

[viii] York, Geoffrey. “Once close to extinction, South Africa’s first people have a new claim on life.” The Globe and Mail, 29 Dec. 2016, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/how-africas-first-people-are-hunting-for-theirfuture/article33345214/#:~:text=The%20San%20%E2%80%93%20sometimes%20called%20the,traced%20back%20140%2C000%20years%20here.

2 replies on “Dicynodont Cave Art in South Africa: Fact or Fiction?”

I can’t believe you don’t have more followers! Your articles are amazing and I really appreciate you take the time to provide photos and all of your sources. Thank you for making this blog and I hope you never stop posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If that cave art turns out to be the first gorgonopsian paleoart ever that would be huge news.

LikeLike