Could Raptors fly? Maybe not, but a new study suggests they could flap – an essential step for the evolution of powered flight.

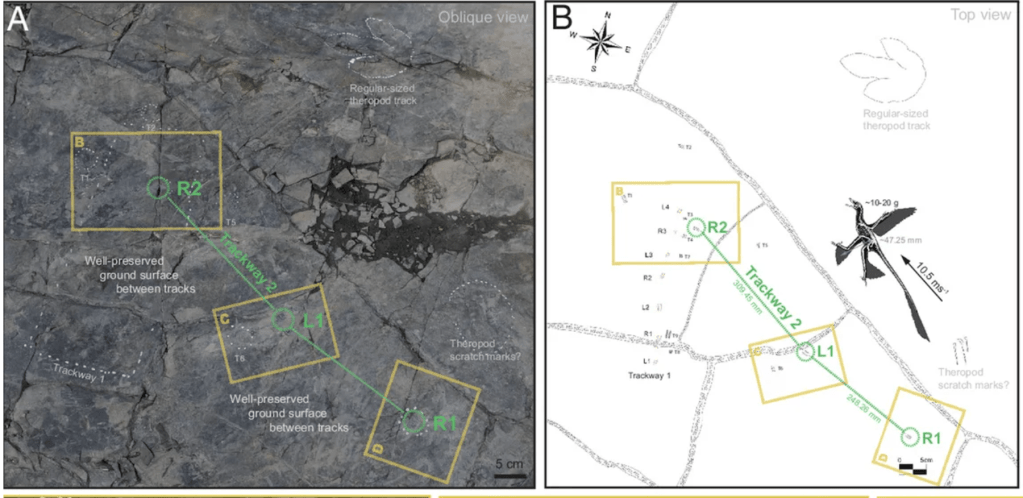

On October 21st, a team of paleontologists led by Alexander Dececchi of Dakota State University published an examination of a Dromaeosaurid trackway from the Early Cretaceous Jinju Formation of South Korea[i]. Assigned to the Ichnotaxa Dromaeosauriformipes rarus, the footprints are amongst the smallest recorded dinosaur fossils ever identified but are easily identifiable as a raptor based on the two toes present in each footprint[ii].

Despite their diminutive size, the authors noticed something strange about the trackway: the gap between strides was massive. In fact, the ratio of stride to footprint length was greater than any other observed dinosaur trackway by a considerable amount. Given that the stride length was measured to be over 50x the length of the footprint, it seems impossible that the small raptor was walking at the time of preservation. Unless it was on Looney Tunes stilts, of course!

Previous calculations of speed estimated the Dromaeosauriformipes to be running at approximately 37.8 km/hour, a quick but normal estimate of speed. However, when the authors calculated the Froude number for the trackway – a useful statistic for estimating movement mechanics and the forces associated[iii] – they found it to be an unreasonably high 238. For reference, the Froude number of a Cheetah is almost half the value found in Dromaeosauriformipes. The authors concluded that the forces associated with a Froude number that high would be impossible for the owner of the trackway to overcome in a normal sprint. Thus, they were forced to consider if another factor was influencing the stride length of the Raptor.

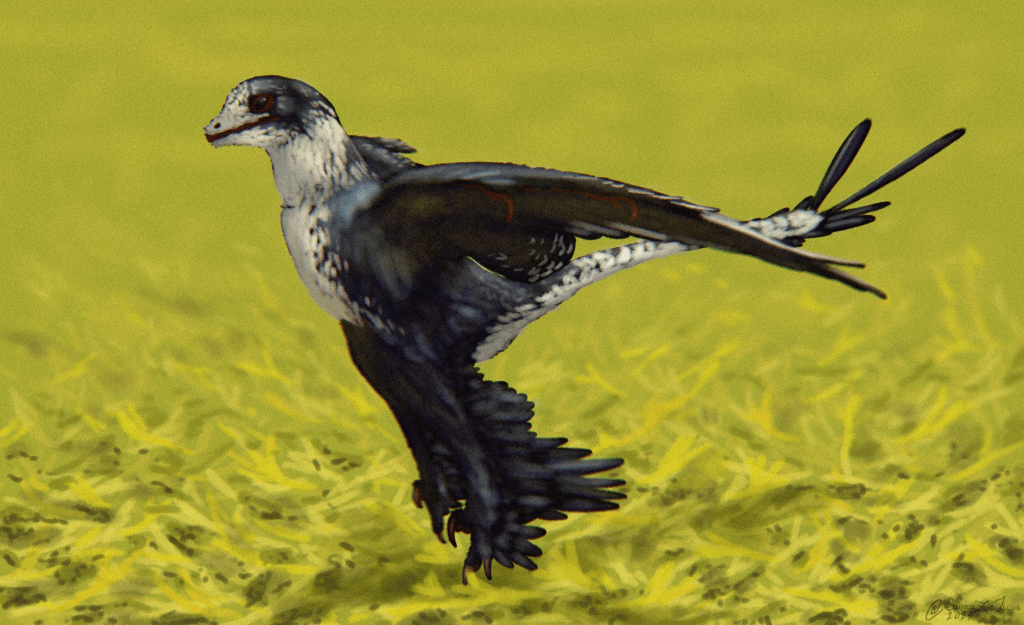

Enter the flapping. By using data from a specimen of Microraptor, a winged Dromaeosaur closely related to the trackway species, the study found that the exceptional stride lengths were likely created when the Dromaeosaur lifted off the ground from wing propulsion. In Microraptor models in which flapping was accounted for, similar Froude numbers were generated, providing solid evidence that the Jinju trackway was produced by a Raptor that was flapping while running.

This finding is fascinating. While it does not necessarily mean that the raptor was flying, it was using a basic wing structure to generate lift and takeoff. Why this behaviour was used is currently unclear, though it may have aided in propelling the animal forward or to help climb vertical surfaces, a behaviour known as wing-assisted incline running (WAIR[iv]). In any scenario, Raptors appear to have been using wings to lift themselves off the ground to aid in locomotion.

More interesting is how flapping in non-avian dinosaurs is related to the flapping seen in birds. Flapping to aid in aerial locomotion may have evolved on two separate occasions in theropods, or alternatively, the behaviour may have been present in a common ancestor of the two lineages. In either scenario, the presence of flapping in dinosaurs closely related to birds goes a long way in providing clues to the early evolution of flight in birds.

Another important takeaway from the study is its implications on Dromaeosaur behaviour. Paleontologists have long believed that the Dromaeosaur subfamily Microraptoria, which includes Microraptor and the raptor who left the Jinju trackway, utilized aerial locomotion. The extent of this behaviour is debated; some believe they were gliders[v], while others believe they were capable of true powered flight[vi]. The findings of this study lend support to the latter, though I believe it shouldn’t be thought of in a black-or-white manner. Perhaps it glided, but occasionally used flapping to change trajectories or gain lift.

After all, if there’s anything that we’ve learned about prehistoric animals, it’s that their behaviours are more unique than anything we could have imagined.

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the artists noted with each piece. Header image courtesy of Julius Csotonyi, found here.

Works Cited:

[i] Dececchi, T. Alexander et al. “Theropod trackways as indirect evidence of pre-avian aerial behavior.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 121, no. 44, October 2024, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2413810121

[ii] “Smallest dinosaur footprint.” Guinness World Records, 12 Dec. 2018, http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/smallest-dinosaur-footprint#:~:text=The%20diminutive%20prints%2C%20which%20were,or%20a%20fully%20grown%20dinosaur.

[iii] Lees, John, et al. “Locomotor preferences in terrestrial vertebrates: An online crowdsourcing approach to data collection.” Scientific Reports, vol. 6, no. 1, July 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28825.

[iv] Bundle, Matthew W., and Kenneth P. Dial. “Mechanics of wing-assisted incline running (WAIR).” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 206, no. 24, Nov. 2003, pp. 4553–64. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00673.

[v] Dyke, Gareth, et al. “Aerodynamic performance of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor and the evolution of feathered flight.” Nature Communications, vol. 4, no. 1, Sept. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3489.

[vi] Pittman, Md. Potential for powered flight development in microraptorine dromaeosaurids, bird-like ‘raptor’ dinosaurs from the Cretaceous period. 2019, hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/273258.