If asked, I would argue that the most iconic moment of the documentary series Prehistoric Planet is the Carnotaurus dance scene. Featured in episode 5 of season 1, a male Carnotaurus is seen performing a series of elaborate dance moves – including waving his arms like he just doesn’t care – within a carefully constructed display arena to woo a potential mate. It’s a fun scene, but one question I am sure many have wondered is whether dinosaurs really practised such behaviours.

If the fossil record is any indication, the answer is yes. For the dancing part, at least; the flailing arms are a little more speculative!

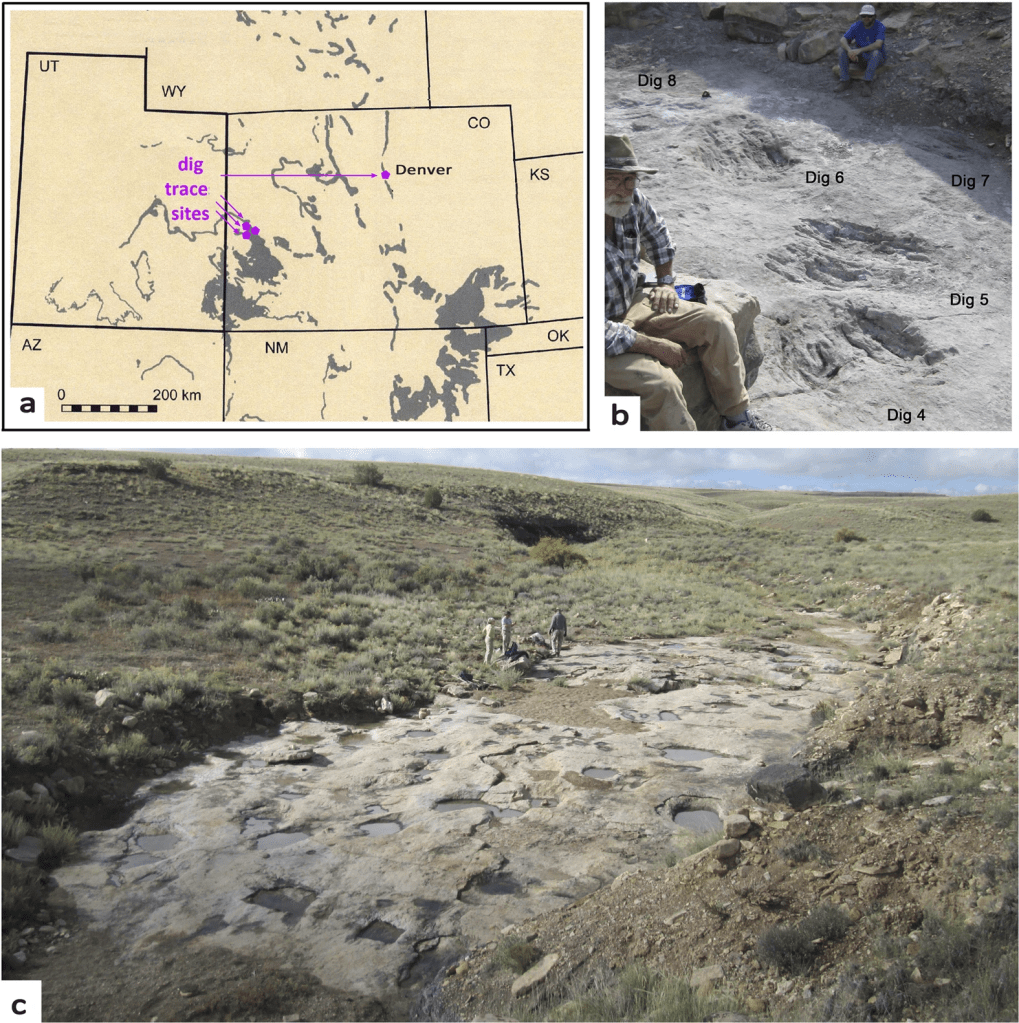

In 2016, paleontologists led by Martin Lockley of the University of Colorado published a study describing several strange markings found in the central United States[i]. The trace fossils, which were made some time during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 100 million years ago, consist of large depressions in the rock often with scratch marks within. Spanning across several sites in Colorado, these imprints were found in high concentrations with multiple sizes preserved, signalling the presence of different individuals at these localities.

The immense size of the traces, some of which reach 2 meters in diameter, led paleontologists to conclude that they were produced by a dinosaur, likely a genus of theropod. Why they made such patterns was more unclear. The configuration and distribution of the scratch marks did not resemble typical dinosaur trackways, indicating that they were not made by animals simply walking or running through the landscape.

Another possibility was that the dinosaurs were attempting to dig a nest. However, this also proved to be a poor fit for the markings, as dinosaur nests typically have a definitive shape with a well-defined ridge serving as a boundary. The lack of eggshells and other indications of juvenile dinosaurs supports this notion, as it would be logical to find some evidence of baby dinosaurs in the depressions meant to house them. Additionally, other dinosaur nests belonging to Oviraptorids, Sauropods, and Hadrosaurs all lack visible scratch marks within, making this case unlikely.

What about digging for water? Modern animals practise this behaviour in times of extreme drought; could they have quite literally followed in the footsteps of dinosaurs? It is possible, though Lockley and company noted that, if successful, finding water below the surface would wash away the scratch marks that define the trace fossils. Another possibility discussed is that the scrapes are indicative of territorial markings akin to modern mammals, but the large clusters of trace fossils are unlike what is seen in modern taxa.

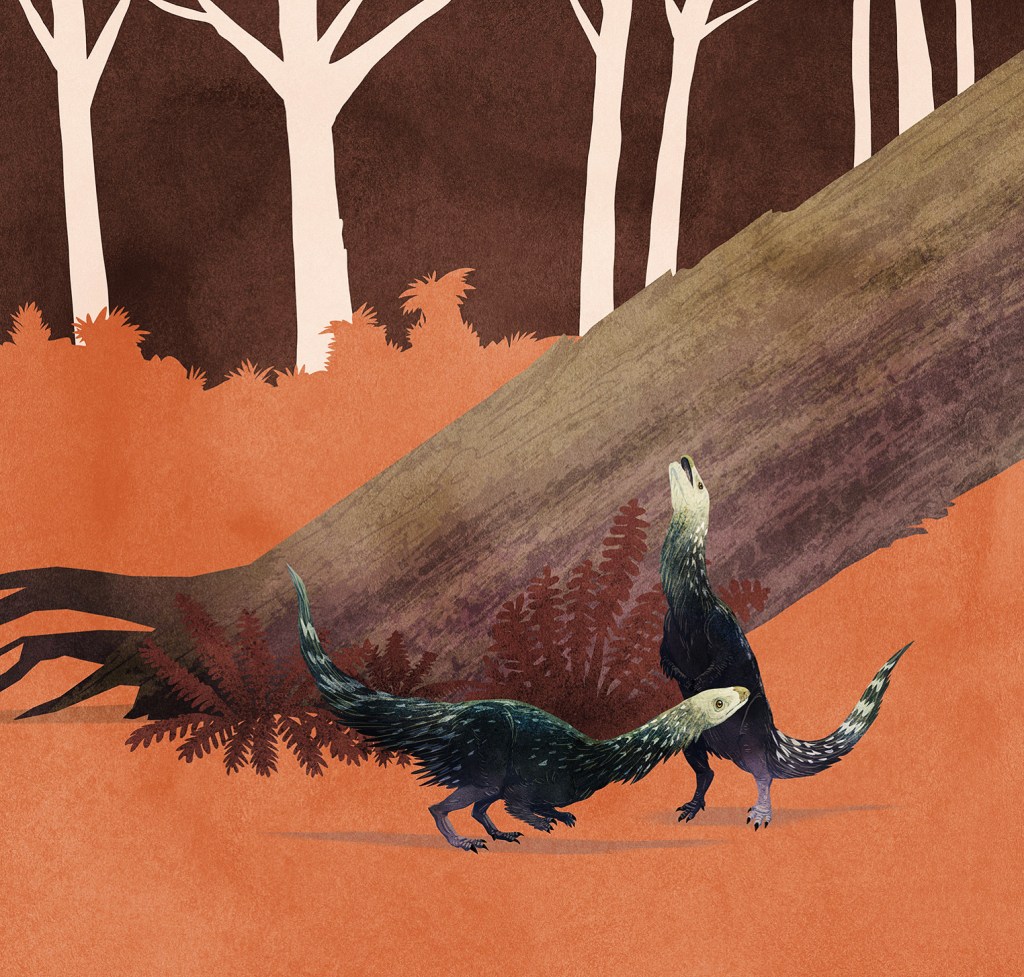

Instead, the authors proposed a fascinating reason behind the creation of the markings: they were a bi-product of a prehistoric dance. In this theory, colonies of male theropods gathered seasonally in “display arenas” to attempt to pursue potential females by performing intricate, choreographed rituals. As they performed their dance, the theropods would have kicked up dirt and scratched at the ground, leaving a series of depressions and scratch marks behind.

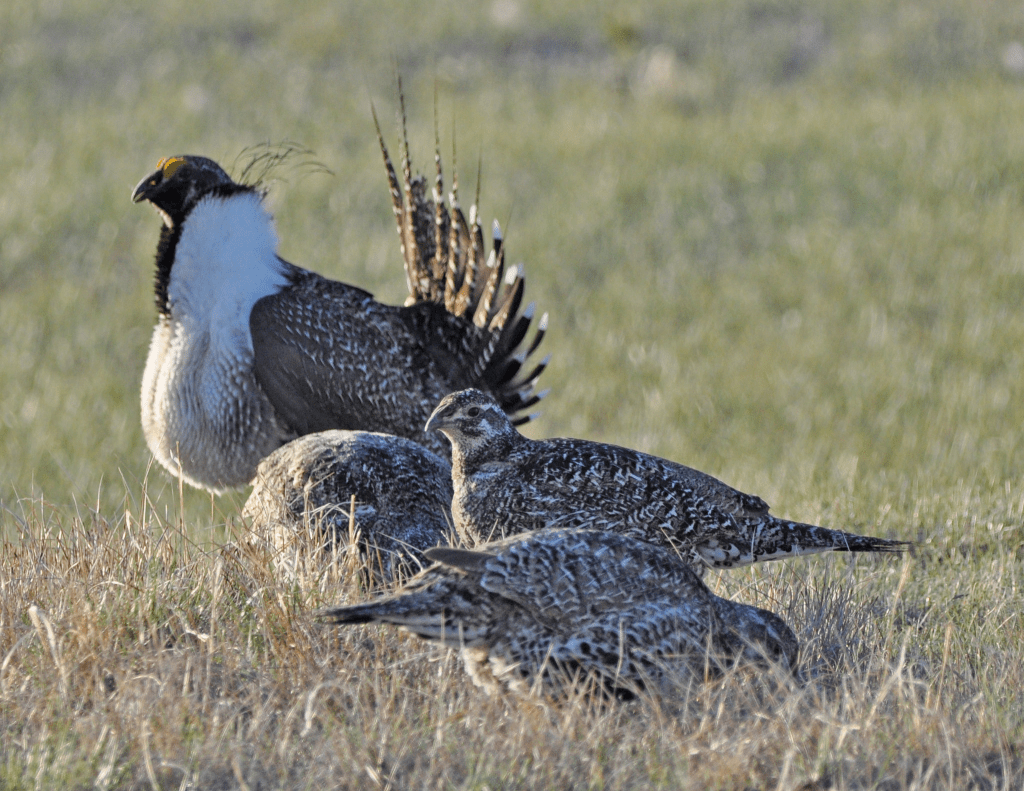

This theory was inferred based on the behaviour of modern analogues, particularly birds such as the Greater Sage-Grouse and several Birds-of-paradise. Known as “lekking,” this behaviour sees large colonies of males gather at a given location and “strut their stuff,” advertising themselves to onlooking females. This behaviour would be consistent with the seemingly random arrangement of footprints and explains why they cluster in large areas. It also explains why a variety of sizes appear to be present, as in modern species, both sub-adults and mature dinosaurs could attempt to participate in the ritual.

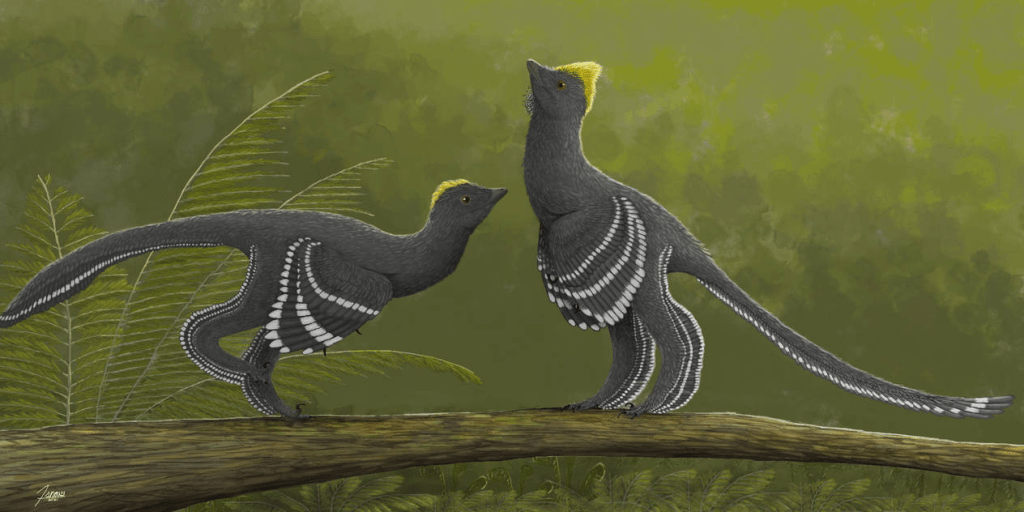

The implications of such behaviours are immense. First, if we look at the lek in comparison with modern birds, it implies a strong level of sexual dimorphism between males and females. Males of lekking species such as the Sage-Grouse and Birds-of-paradise often have colourful and intricate feather patterns designed to enhance their display. Females usually lack such vibrant plumage, instead possessing more muted colours that make them better able to hide from predators without being noticed.

Whether this was also the case with dinosaurs is debatable. Sexual dimorphism has been proposed for several dinosaurs, including the Stegosaur Hesperosaurus and an Ornithomimid herd, but it is not something observed across all dinosaurs[ii][iii][iv]. Additionally, females having more muted colours may not have been necessary for a large theropod, given that they were (presumably) the largest predators in their ecosystem. Regardless, the prevalence of dimorphism in lekking birds suggests their prehistoric ancestors may have displayed similar traits.

Speaking of birds, the use of leks by a theropod dinosaur pushes back the use of the behaviour in Dinosauria – which yes, includes birds – by several million years. Interestingly, the dinosaur that made the depressions is not a direct ancestor to modern birds, as early birds had already evolved by the Late Cretaceous. This could mean one of two things. First, lekking behaviours were present in the earliest members of Theropoda, with future descendants continuing this dancing tradition for over 150 million years. Alternatively, the behaviour evolved independently multiple times in the theropod lineage. This would be more realistic, as only a fraction of the 10,000+ known bird species utilize lekking to display for females, meaning it is unlikely to have been ancestral in the family.

This is not to say the first birds didn’t practise lekking; it’s just that we don’t presently have evidence for it.

In fact, independent evolution of leks appears to be common throughout the animal kingdom. Everything from dragonflies to frogs and even fish have been observed using leks for mating purposes[v], making it a common behaviour. Apparently, there is some benefit from a reproductive standpoint for large congregations of males to show off their stuff to onlooking females! It’s kind of like a dinosaur version of The Bachelorette. Who will get the rose?

My money is on the Ceratopsians. Why evolve such tremendous skull ornamentation if not for beauty?

The fossilized markings made during these mating rituals have provided paleontologists with a unique glimpse into the reproductive lives of dinosaurs. While fossils of eggshells and nests have provided us with plenty of information about the later stages of reproduction, the earliest parts of courtship and display were previously unclear. Now, incredible fossils have revealed that some dinosaurs had quite the romantic side to them.

I wonder if they celebrated Valentine’s too…probably not, given that lekking events usually occur in the spring as opposed to the winter. Alas, Have a happy Valentine’s Day everyone!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come credit of the artists noted with each image. Header image courtesy of…

Works Cited:

[i] Lockley, M. G., McCrea, R. T., Buckley, L. G., Lim, J. D., Matthews, N. A., Breithaupt, B. H., Houck, K. J., Gierliński, G. D., Surmik, D., Kim, K. S., Xing, L., Kong, D. Y., Cart, K., Martin, J., & Hadden, G. (2016). Theropod courtship: large scale physical evidence of display arenas and avian-like scrape ceremony behaviour by Cretaceous dinosaurs. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18952

[ii] Ludwig, S. A., Smith, R. E., & Ibrahim, N. (2023). Sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. eLife, 12. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.89158

[iii] Saitta, E. T. (2015). Evidence for Sexual Dimorphism in the Plated Dinosaur Stegosaurus mjosi (Ornithischia, Stegosauria) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western USA. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0123503. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123503

[iv] Mallon, J. C. (2017). Recognizing sexual dimorphism in the fossil record: lessons from nonavian dinosaurs. Paleobiology, 43(3), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2016.51

[v] Fiske, P., Rintamäki, P. T., & Karvonen, E. (1998). Mating success in lekking males: a meta-analysis. Behavioral Ecology, 9(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/9.4.328

One reply on “Dinosaur Dance Marks: A Prehistoric Courtship Ritual”

Several years ago, the eminent British paleontologist Dr. David Norman did a lecture on dinosaur behavior, and several of the things which he spoke of are mentioned in your article. You can watch the video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KB2Q9ARMEbE

LikeLike