It has been said that our tastes change as we age. In the case of one Chinese dinosaur, this notion was taken to the absolute extreme.

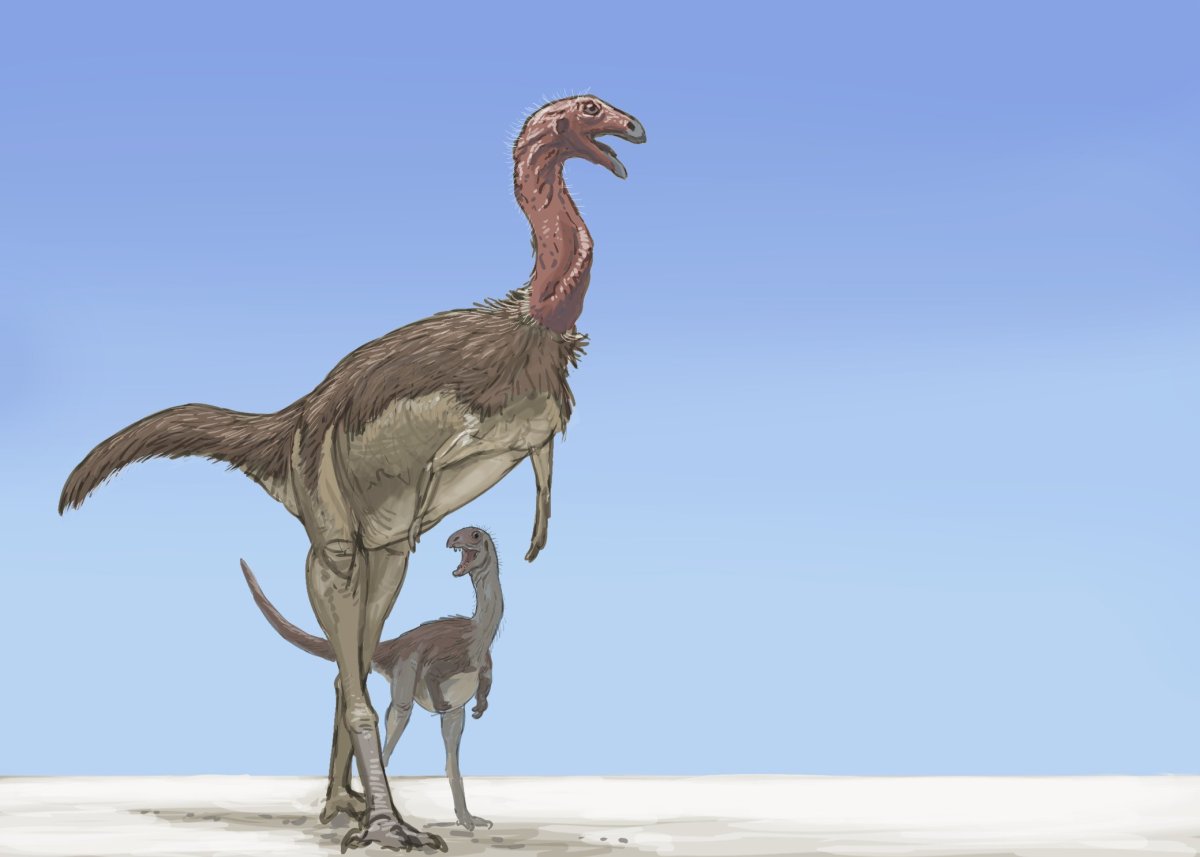

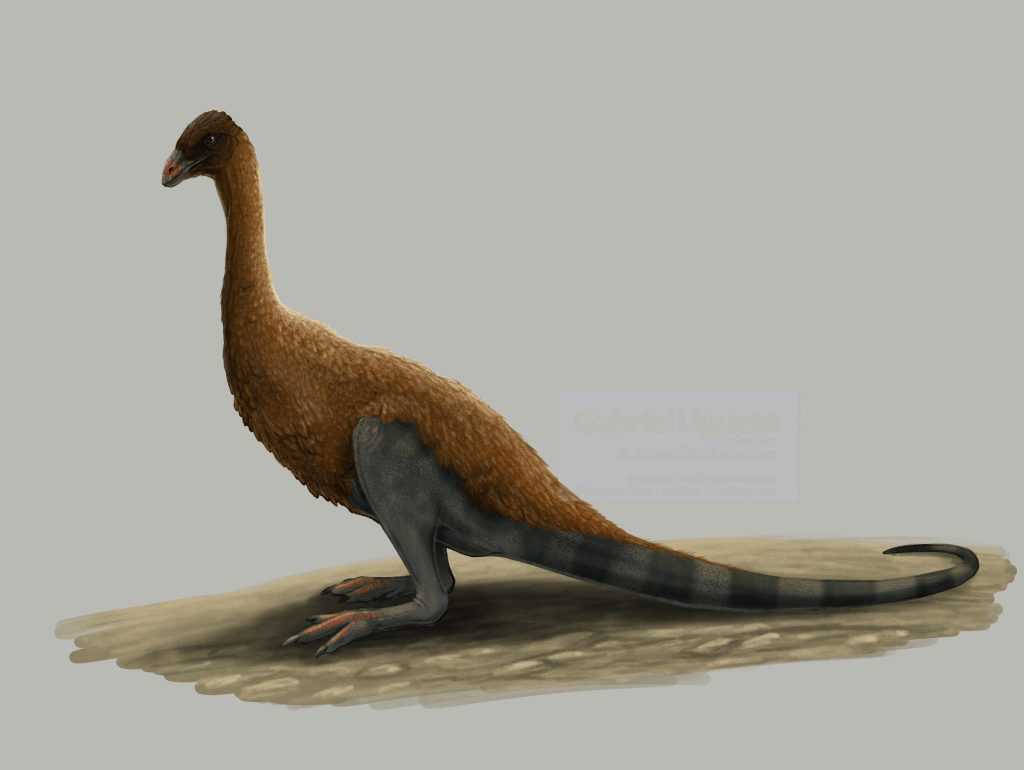

Limusaurus inextricabilis, a genus of Ceratosaur from the Late Jurassic Shishugou Formation of northwestern China, is notable for a few reasons. When it was first described in 2009, the forearms of Limusaurus made headlines based on the reduction of their first digits, helping provide further evidence of the connection between dinosaurs and their avian descendants[i]. While the relevancy of this discovery to bird evolution has been debated in subsequent years[ii], its publication in Nature brought a lot of attention to the diminutive theropod.

Stranger yet was the diet of Limusaurus. Despite being a Ceratosaurid – a lineage of theropods which contains large carnivores such as the Jurassic Ceratosaurus and the Cretaceous Abelisaurids – Limusaurus was herbivorous. This behaviour has been interpreted based on two curious features. First, Limusaurus possessed a toothless beak, a trait which is observed in more derived, potentially herbivorous Theropod lineages (such as Oviraptorids and Ornithomimids), but is absent in most Ceratosaurs. Second, the presence of gastroliths – or stones in the stomach swallowed by the animal while alive – associated with several Limusaurus fossils is believed to have aided in digestion of tough plant matter.

But not all Limusaurus specimens are so well-suited for herbivory. In fact, many of them don’t have beaks at all! Instead, several Limusaurus specimens housed at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences contain a mouth full of small teeth[iii]. Between the premaxilla and maxilla of the upper jaw and the dentary of the lower jaw, a minimum of 34 teeth are observed in these specimens. Not quite as toothless as you would expect for a supposedly herbivorous dinosaur!

So, what gives? As it turns out, all toothed specimens of Limusaurus represent juveniles of several different growth stages. Paleontologists led by Shuo Wang have identified six different age groups of Limusaurus fossils, with the two youngest containing teeth that became replaced by a beak in the fourth state and beyond[iv]. As Limusaurus grew, its tooth count dwindled from 42 in the youngest individuals to 34, then finally to 0. As the dinosaur made continuous donations to the tooth fairy, the structure of the bones that once contained teeth morphed into the beak present in adults, laying the groundwork for herbivorous diets.

As you can imagine, such profound changes to dental anatomy are rare in dinosaurs. In fact, the transition from toothed juveniles to toothless, beaked adults seen in Limusaurus is the only known example of such phenomena in non-avian dinosaurs. It is only known from a handful of cases in the entire animal kingdom, with the most famous example being the living Platypus[v]. Perhaps the oddity of the mammalian kingdom is the perfect analogy for the oddity of Ceratosauria?

The secrets of why Limusaurus underwent such changes was stored in their bones. In recent years, a technique known as isotope analysis – a method which compares the concentrations of isotopes (variations of atoms with different weights) in bones to analogues – has been used by paleontologists to decipher questions pertaining to dinosaur diet, migratory behaviours, and ecology. To assess diet, the ratios of elements like Carbon 13 (C13) and Oxygen 18 (O18) – two isotopes whose presence is impacted by environmental factors and dietary preferences – can be compared alongside analogous taxa to see if a given species plots closer to known carnivores or known herbivores[vi].

Given the discrepancy in anatomy between growth stages of Limusaurus, such tests were deemed perfect for analysing the diets of adults and juveniles. After comparing the ratios of C13 and O18 with contemporary sauropods (herbivorous) and theropods (predatory) from the Shishugou Formation, paleontologists found something fascinating. While adults consistently plotted in similar ranges to known herbivores, the ratios observed in juveniles were far more variable, with some individuals plotting in the herbivorous range while others were far closer to predators[vii]. This suggests that juveniles practised omnivory, or the behaviour of eating both meat and plants, while adults stuck solely to plants. This finding is supported by the lack of gastroliths in juvenile specimens, interpreted as a reduced need for extra measures to aid in the digestion of vegetation.

Why did Limusaurus practise such behaviour? One proposed reason is to decrease the amount of competition with adults. By consuming different foods, the adults and juveniles were able to partition the resources available to them, thus preventing overlap in ecologies and allowing the two to exploit different niches. This may have been a significant adaptation for the genus, giving them an increased chance of survival by expanding the amount of food available depending on their age.

This behaviour – known as an Ontogenetic Niche Shift (ONS) – has become widespread in paleontological theory in recent years, particularly as it pertains to Tyrannosaurs[viii]. Some paleontologists cite ONS as the reason why so few medium-sized theropods have been discovered in Late Cretaceous North America, with juvenile Tyrannosaurids consuming different prey than their parents and thus occupying a different role. This theory has been supported by the discovery of a juvenile Gorgosaurus libratus that contained Oviraptorid legs in its stomach, a much different prey item than the Hadrosaurs and Ceratopsians consumed by adults[ix].

For more about that specimen, read the following article from Max’s Blogosaurus.

Even Gorgosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus rex for that matter, didn’t go through the level of change witnessed in Limusaurus. While their diets may have differed, even the strangest Tyrannosaur can’t claim it switched from being a toothed omnivore to an edentulous herbivore by the time it reached adulthood!

Thank you for reading this article! If you’d like to know more about another extreme example ONS and the debate it has caused, read about Nanotyrannus here at Max’s Blogosaurus!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the artists noted alongside each piece. Header image courtesy of Joschua Knüppe, whose terrific artwork can be found at his twitter account linked here.

[i] Kaplan, M. 2009. Dinosaur’s digits show how birds got wings. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2009.577

[ii] Vargas, Alexander, Wagner, Günter, and Gauthier, Jacques. 2009 Limusaurus and bird digit identity. Available from Nature Precedings http://hdl.handle.net/10101/npre.2009.3828.1

[iii] Wang, S., Stiegler, J., Amiot, R., Wang, X., Du, G., Clark, J. M., & Xu, X. 2016b. Extreme ontogenetic changes in a ceratosaurian theropod. Current Biology 27(1): 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043

[iv] Wang, S., Stiegler, J., Amiot, R., Wang, X., Du, G., Clark, J. M., & Xu, X. 2016b. Extreme ontogenetic changes in a ceratosaurian theropod. Current Biology 27(1): 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043

[v] Asahara, M., Koizumi, M., Macrini, T. E., Hand, S. J., & Archer, M. 2016. Comparative cranial morphology in living and extinct platypuses: Feeding behavior, electroreception, and loss of teeth. Science Advances 2(10). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601329

[vi] Benton, M. 2023. Dinosaur behavior: An Illustrated Guide. Princeton University Press.

[vii] Wang, S., Stiegler, J., Amiot, R., Wang, X., Du, G., Clark, J. M., & Xu, X. 2016b. Extreme ontogenetic changes in a ceratosaurian theropod. Current Biology 27(1): 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043

[viii] Schroeder, Katlin. 2022. “Ontogenetic Niche Shift as a Driver of Community Structure and Diversity in Non-Avian Dinosaurs.” https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/397

[ix] Therrien, F., Zelenitsky, D. K., Tanaka, K., Voris, J. T., Erickson, G. M., Currie, P. J., DeBuhr, C. L., & Kobayashi, Y. 2023. Exceptionally preserved stomach contents of a young tyrannosaurid reveal an ontogenetic dietary shift in an iconic extinct predator. Science Advances 9(49). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adi0505