After years of rumours, conference talks, several leaked photos, and a teaser trailer for a bloody dinosaur, the second species of Spinosaurus is finally here.

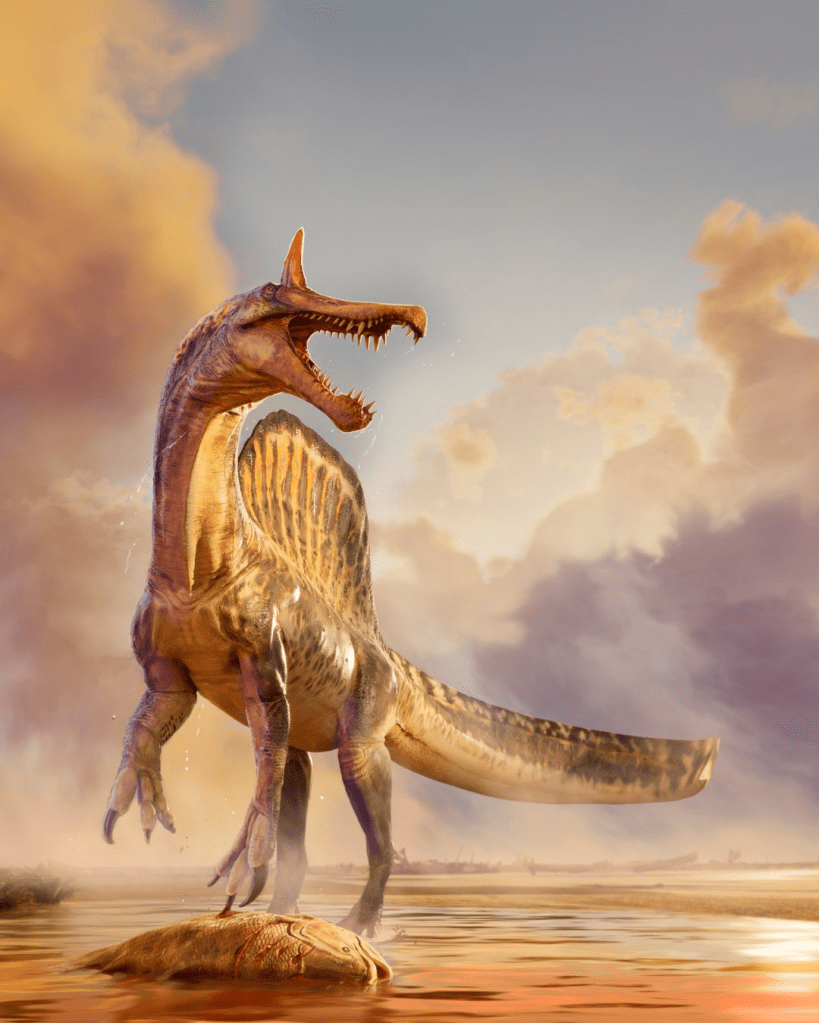

Meet Spinosaurus mirabilis, the “astonishing spined lizard” and owner of one of the most spectacular crests in the dinosaur family:

Described in the journal Science by Paul Sereno and a large team of paleontologists, fossils of S. mirabilis were first discovered in the African country of Niger in 2022. Inspired by reports of spinosaur fossils discovered in the country during the 1950’s, Sereno’s team focused on examining a remote locality known as Sirig Taghat located in central Niger.[i] After receiving aid from local guide Abdul Nasir, the team’s exploration of Sirig Taghat at a site known as Jenguebi uncovered whole scores of fossils from the Late Cretaceous Farak Formation (~95 million years old), including those of two-unnamed sauropod species, the large theropod Carcharodontosaurus, crocodiles, pterosaurs, and large fish.[ii]

Plus, several specimens of Spinosaurus, of course.

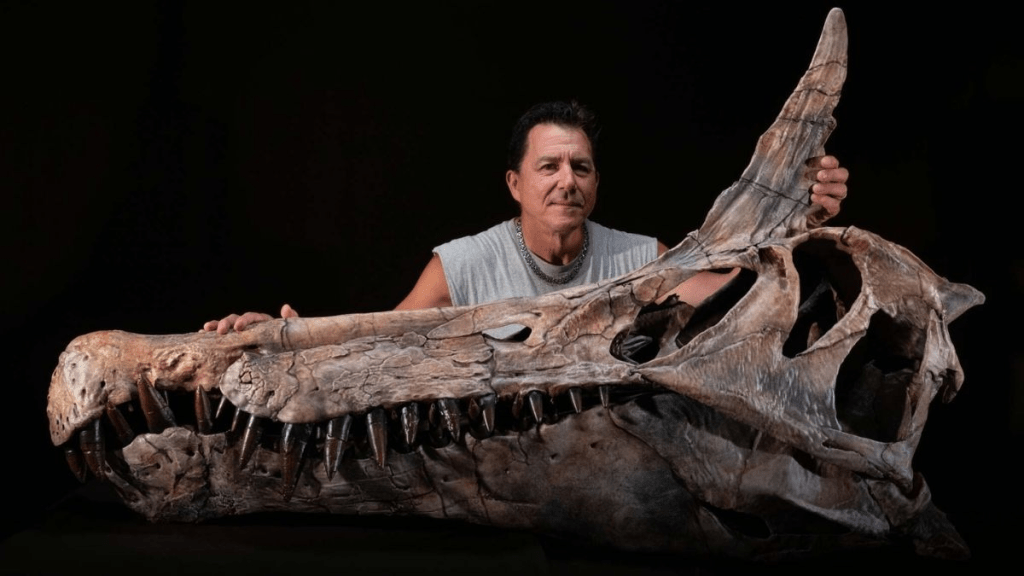

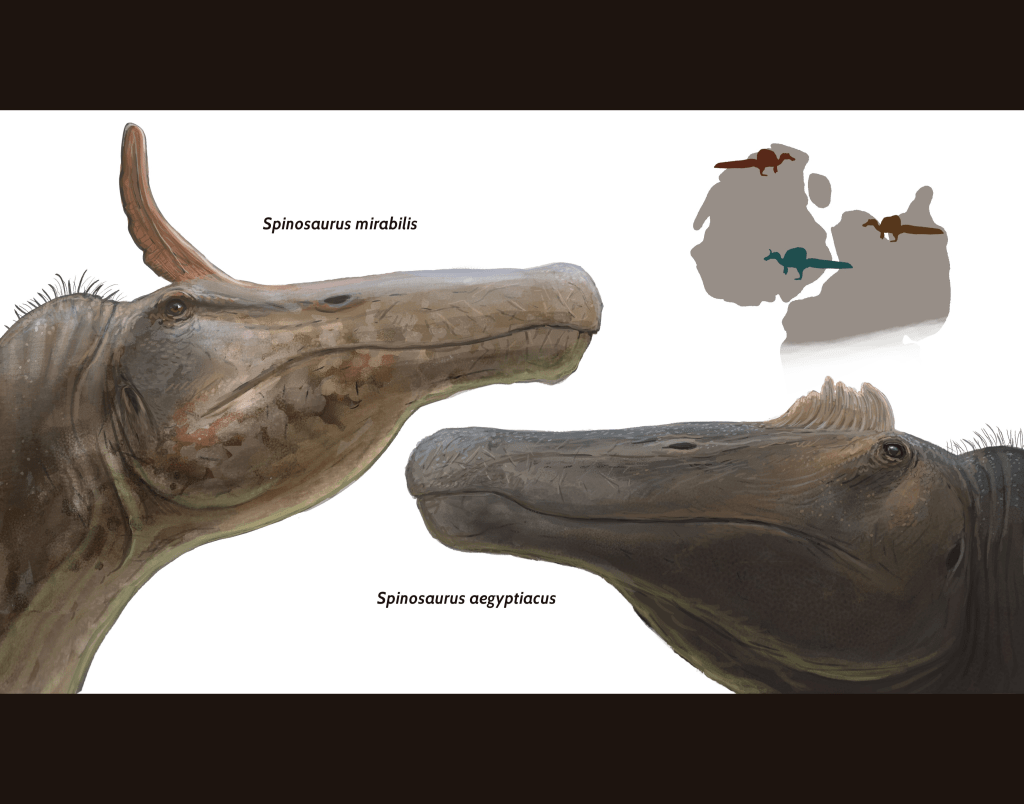

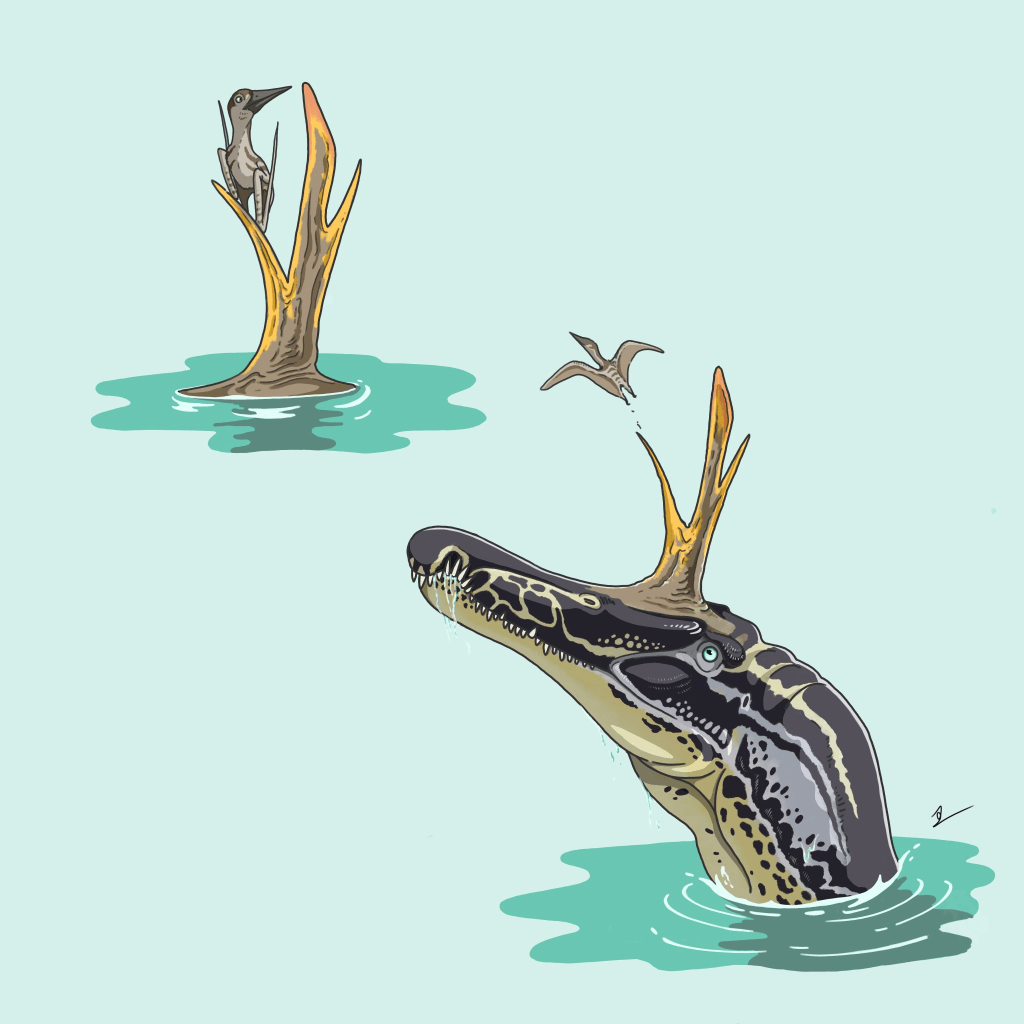

At present, S. mirabilis is represented by at least 4 subadult individuals and comprises material from the skull, vertebrae, and hindlimbs. The most prominent feature of the species, and what sets it apart from Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, is the large facial crest that adorns the roof of the skull. In S. mirabilis, the crest – which is comprised of the nasal and parts of the prefrontal bones – is a massive sickle shape, which would have been even larger in life due to the presence of a keratinous sheath overtop. Additionally, all three known crests of S. mirabilis are asymmetrical; in the holotype specimen, the crest bends laterally to an extreme degree.[iii]

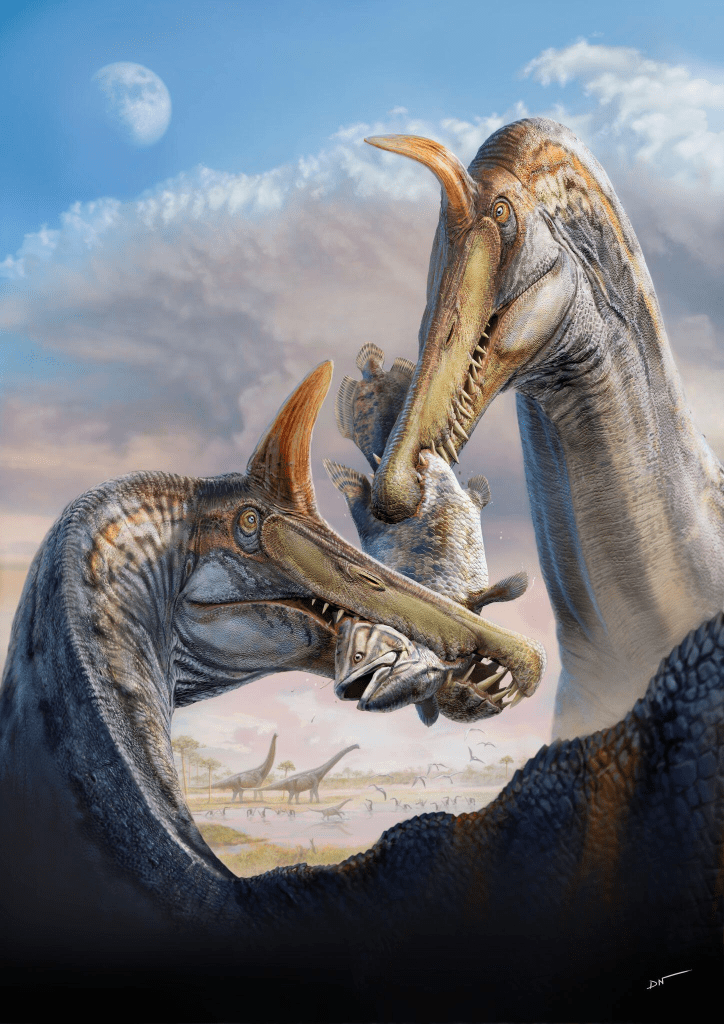

In S. aeygiptiacus, the crest is much smaller and tappers at its apex into a relatively flat structure. However, it seems very likely that both species used the crest for the same purpose: visual communication. In tandem with their infamous sails, the crests likely served as a sociosexual signal to other Spinosaurus for reproduction, territoriality, or other purposes. Even for immature individuals, the crest would been key for survival in the river systems of prehistoric Niger.

Though the crest is the most noteworthy difference between S. mirabilis and S. aegyptiacus, a few others are present. First, the teeth at the front of the maxilla have larger gaps between them in S. mirabilis than S. aegyptiacus. Second, the snout is relatively flat in S. mirabilis, whereas the snout of S. aegyptiacus features a more prominent slope. Third, while not considered diagnostic by the authors, the front of the mandible (or lower jaw) in S. mirabilis is much flatter than the rounded jaw of S. aegyptiacus. Fourth, the tibia – or one of the lower limb bones – is proportionally longer in S. mirabilis than S. aegyptiacus, though I do wonder if this is the result of the subadult ages of S. mirabilis than any actual difference.

Beyond the fascinating crest of S. mirabilis, Sereno’s study also does a wonderful deep dive (pun intended) into the evolution of spinosaurids, which they propose occurred in three separate stages. First, a late Jurassic divergence from other theropods wherein they gained the characteristics used to define the family. Second, an Early Cretaceous radiation around the Tethys seaway that divided spinosaurids into two families: baryonychines and spinosaurines. Third, a final radiation of spinosaurines where several genera – Spinosaurus from Africa and Oxalaia from Brazil – grew colossal. While none of this information is new, it is nice to see it added to scientific literature where the sequence of trait evolution is explored with more depth.

The other topic addressed by Sereno’s study is the cloud hovering over Spinosaurus research: what was the extent of its aquatic behaviours? As a quick refresher, much of the debate and subsequent controversy around Spinosaurus stems from how paleontologists believe it foraged for food. While some paleontologists (primarily Nizar Ibrahim) view it as a diving, underwater pursuit predator, others see it as a wading predator that would stalk shorelines in anticipation of food. The diver vs. wader debate has continued for the better part of the last decade, though the last studies published favoured the wading hypothesis.

Given that Paul Sereno is seen as the unofficial champion of the wading hypothesis, it’s not exactly surprising that this stance is favored for S. mirabilis. This main argument comes down to the location of S. mirabilis fossils, which would have been ~500-1,000 kilometers from the nearest ocean during the Cretaceous. The authors use this inland setting to justify the wading predator hypothesis, noting that no large, fully aquatic tetrapod lives that far inland in both modern and prehistoric times.

While I currently lean towards the wading-predator hypothesis, I’m not convinced that this line of evidence is satisfactory to addresses previous arguments. If its habitat in Niger was a massive floodplain that featured deep, wide river channels, it seems plausible that Spinosaurus could still have still practised diving behaviours. Fossils from Jenguebi include several large fish species – including the infamous sawskate Onchopristis and a giant Polypterid fish that is estimated to have reached 3 meters (12 feet) long – meaning food was available for a large aquatic predator. Being inland doesn’t preclude Spinosaurus mirabilis from aquatic behaviours unless the specific ecosystem was unable to support such behaviours.

Additionally, there is precedence for a typically coastal, diving species to be found inland. May I introduce you to the swimming ground sloth Thalassocnus? While Thalassocnus fossils are typically found in sediments associated with coastal marine environments, specimens have been found as far as 1,000 kilometers inland.[iv][v] Though these inland sloths weren’t quite as evolved for aquatic behaviours as their coastal brethren, that doesn’t mean those coastal Thalassocnus species weren’t practising diving behaviours.

Which brings us to my second counterargument. Even if we accept that the inland location argues against S. mirabilis being an aquatic predator, what does it mean for S. aegyptiacus? Its fossils are still found in nearshore coastal environments. Certainly, S. mirabilis may have been a wading predator, but extending that conclusion to both Spinosaurus species seems like a leap at this time. Following this logic alone, S. aegyptiacus could still have been a diving predator.

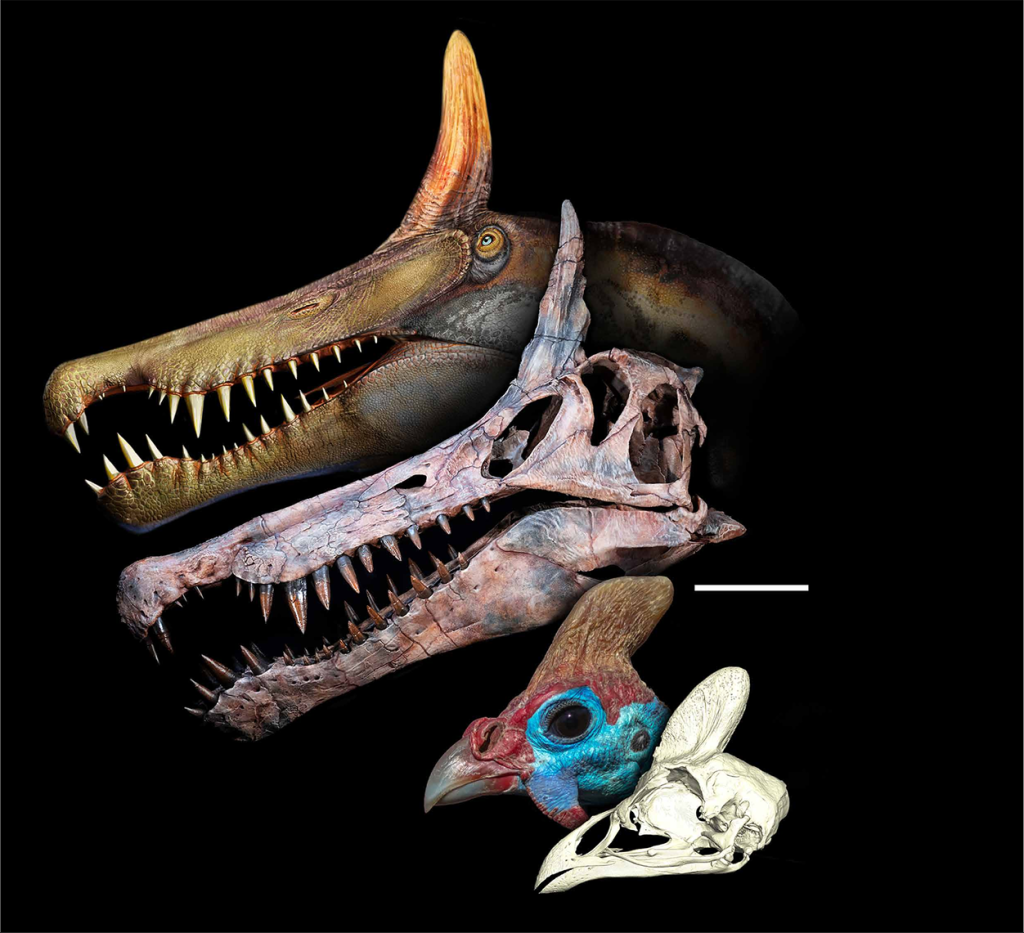

Third, Sereno’s team performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) which plotted several morphological characteristics – such as neck, skull, and limb length – alongside each other to see how Spinosaurus compares to other predators. They found that terrestrial, diving, wading, and aquatic ambush predators all cluster very closely together in distinct morphospaces. When two spinosaurids – Spinosaurus aegyptiacus and Suchomimus – were added to the PCA, the results were interesting. While both genera were found nested between waders and divers, Spinosaurus was extremely close to diving species while Suchomimus was found much closer to waders.

Although the authors use the limb proportions of spinosaurids to group both Spinosaurus and Suchomimus as waders, the position of Spinosaurus next to the diving bird Anhinga is intriguing. Doesn’t its placement on the PCA suggest at least partial – if not specialized – diving in Spinosaurus aegyptiacus? The authors argue this was unlikely, as no living bird practises both diving and wading behaviours, but is it possible that Spinosaurus was an exception?

In any case, my individual critiques focus on the decision to lump the behaviours of S. aegyptiacus with S. mirabilis together and not the proposed behaviours itself. I do tend to think that Spinosaurus was primarily a wading predator who probably specialized along the shorelines of prehistoric rivers and lakes, but the evidence presented in this study is not currently persuasive to me.

The naming of a second Spinosaurus species was always going to be a massive spectacle for paleontology. Not only is Spinosaurus perhaps the most buzzworthy dinosaur on the planet, but the notion of a massive, sickle-shaped crest has instantly made Spinosaurus mirabilis a lightning rod for attention. Plus, with a crest like that, who’s to say it wasn’t a literal lightning rod while alive? Spinosaurus mirabilis may only be a few days old, but it’s already clear that it lives up to its name – astonishing in every conceivable way.

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. Header image comes courtesy of Dani Navarro and Sereno et al. 2026.

References:

[i] Thompson, H. (2026, February 19). This odd-looking new Spinosaurus is reviving an age-old debate. Science. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/spinosaurus-scimitar-head-crest?loggedin=true&rnd=1771614063916

[ii] Sereno, P. C., Vidal, D., Myhrvold, N. P., Johnson-Ransom, E., Real, M. C., Baumgart, S. L., Fontela, N. S., Green, T. L., Saitta, E. T., Adamou, B., Bop, L. L., Keillor, T. M., Fitzgerald, E. C., Dutheil, D. B., Laroche, R. a. S., Demers-Potvin, A. V., Simarro, Á., Gascó-Lluna, F., Lázaro, A., . . . Ramezani, J. (2026). Scimitar-crested Spinosaurus species from the Sahara caps stepwise spinosaurid radiation. Science, 391(6787). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adx5486

[iii] Sereno, P. C., Vidal, D., Myhrvold, N. P., Johnson-Ransom, E., Real, M. C., Baumgart, S. L., Fontela, N. S., Green, T. L., Saitta, E. T., Adamou, B., Bop, L. L., Keillor, T. M., Fitzgerald, E. C., Dutheil, D. B., Laroche, R. a. S., Demers-Potvin, A. V., Simarro, Á., Gascó-Lluna, F., Lázaro, A., . . . Ramezani, J. (2026). Scimitar-crested Spinosaurus species from the Sahara caps stepwise spinosaurid radiation. Science, 391(6787). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adx5486

[iv] Valenzuela-Toro, A. M., Pyenson, N. D., Velez-Juarbe, J., & Suárez, M. E. (2025). Aquatic sloths (Thalassocnus) from the Miocene of Chile and the evolution of marine mammal herbivory in the Pacific Ocean. PeerJ, 13, e19897. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.19897

[v] Quiñones, S. I., Zurita, A. E., Miño-Boilini, Á. R., Candela, A. M., & Luna, C. A. (2022). Unexpected record of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Folivora) in the upper Neogene of the Puna (Jujuy, Argentina). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 42(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2022.2109973