Summer is typically a slow time for paleontology. Most paleontologists take advantage of the warm weather by going out into the field, leading to fewer publications.

Yet, for reasons unknown, July has been an extreme outlier to this trend.

It’s been weird! From mammals attacking dinosaurs to fetal ground sloths, July 2023 has turned into one of the most memorable months for paleontology in a long time. In today’s article, I will discuss some of the most interesting and exciting advancements in the field. Unfortunately, I won’t be able to discuss every new discovery, so please don’t be offended if your favourite isn’t included! With that out of the way, let’s get started.

Mammal vs Dinosaur…

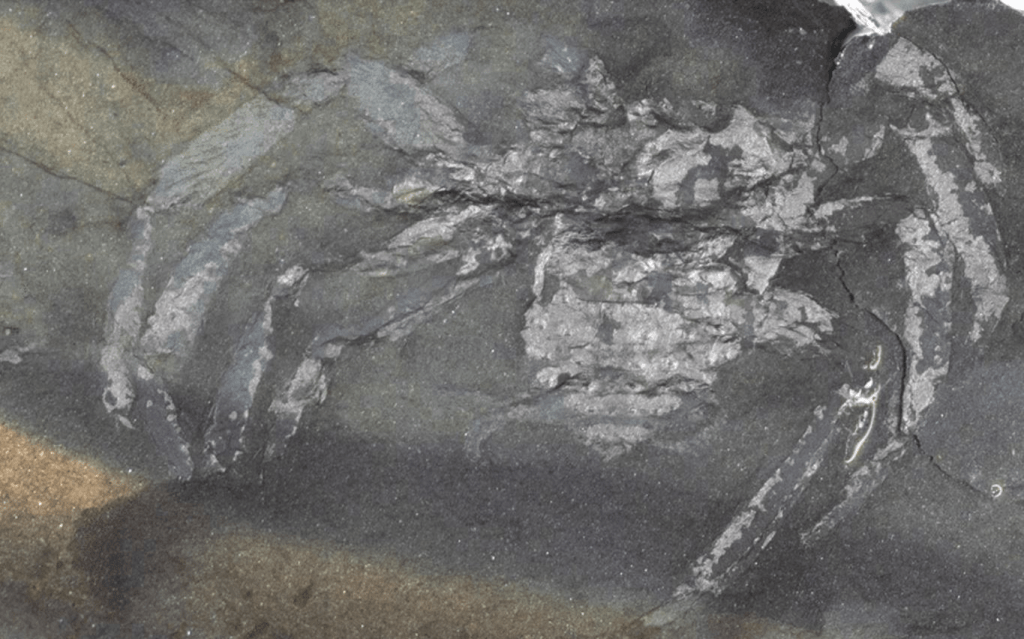

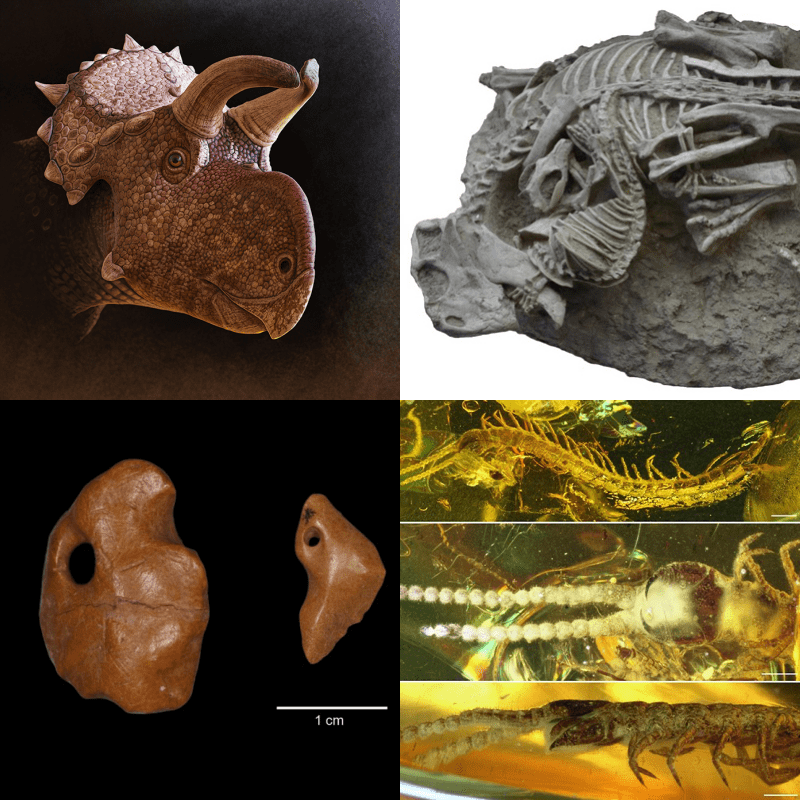

Perhaps the most memorable research published in July was the fossil of a prehistoric mammal locked in combat with a dinosaur. Found in the Yixian Formation of northern China, the specimen captures the moment Repenomamus – a small, badger-like mammal – launches its attack against the ceratopsian dinosaur Psittacosaurus.

Debate has swirled as to whether the mammal was attacking the dinosaur or merely scavenging it. We know from previous fossils that Repenomamus had a taste for young Psittacosaurus (though this too may have been the result of scavenging) and the mammal appears to be attacking the dinosaur from above. However, the size difference and positioning of the skeletons (the mammals leg seems to have gone through the dinosaur) seem odd for an active confrontation. Regardless, the fossil is still incredible, preserved for all eternity by the sporadic volcanic activity of Cretaceous China. (Read “The Fighting Dinosaurs Part 3: Mammals vs Dinosaurs” for more information!)

New Dinosaurs? Try Three!

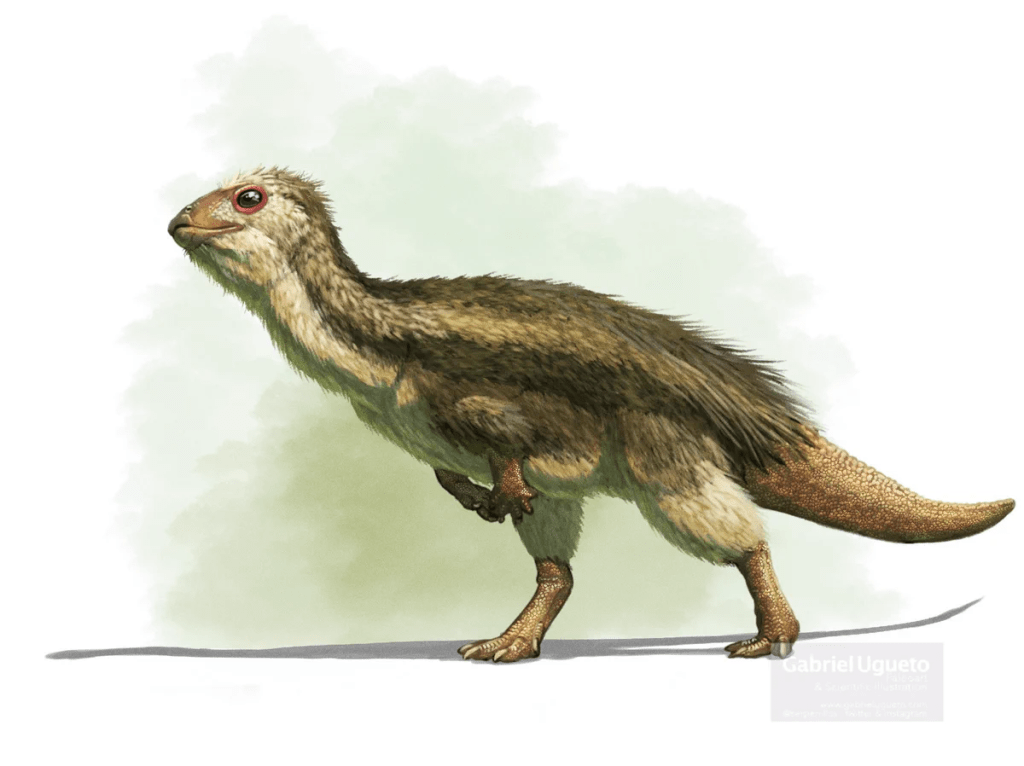

Who doesn’t love some new dinosaurs? The first of our new genera is the small herbivore Minimocursor phunoiensis, discovered in the Phu Kradung Formation of northeastern Thailand. First discovered in 2012, the Jurassic-aged Minimocursor was an early member of the clade Neornithischia, which includes ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs) and hadrosaurs[i]. Thailand has quietly become a hotspot for fossil discovery in recent years, something that the exquisitely preserved Minimocursor illustrates perfectly.

Next is Igai semkhu, a titanosaurian sauropod from western Egypt. Igai – named after an Egyptian deity, the “Lord of the Oasis” – lived towards the end of the age of dinosaurs, approximately 73 million years ago[ii]. Dinosaur fossils from Africa during the end-Cretaceous are rare (due to geological, accessibility, and preservation issues), making new species like Igai even more vital to understanding dinosaur diversity shortly before their extinction.

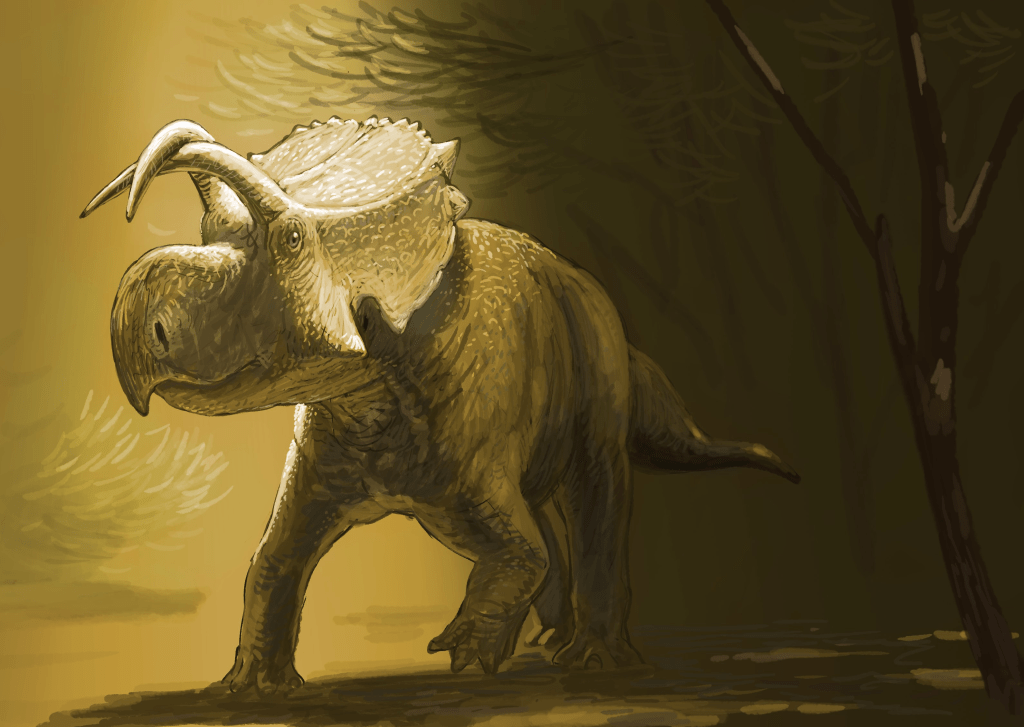

Last up is Furcatoceratops, a genus of ceratopsian from the Judith River Formation of Montana, USA. The name Furcatoceratops translates to “forked horn face” due to the appearance of its curved brow horns[iii]. Furcatoceratops technically isn’t a new discovery, as it was initially announced in 2015 and believed to be a juvenile of the genus Avaceratops, but has now been formally described as its own species. There is even a display at the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center of Furcatoceratops eaten by a Tyrannosaur that predates the reclassification! I guess mystery meat isn’t so bad after all!

More New non-Dinosaur Species!

Dinosaurs weren’t the only group with new species announced in July. Two new sabretooth cat species, Lokotunjailurus chinsamyae and Dinofelis werdelini, were described from the early Pliocene epoch (~5.2 million years ago) of South Africa[iv]. The early Triassic archosaur Mambachiton fiandohana was described from Madagascar, providing a glimpse at one of the earliest armoured reptiles in the fossil record[v]. In southern Germany, the Jurassic-aged Solnhofen limestones produced a bizarre pterosaur, Petrodactyle wellnhoferi. The similarity between the names Petrodactyle with Pterodactylus (another pterosaur from Solnhofen) isn’t subtle. Makes you wonder if paleontologists are running out of names…

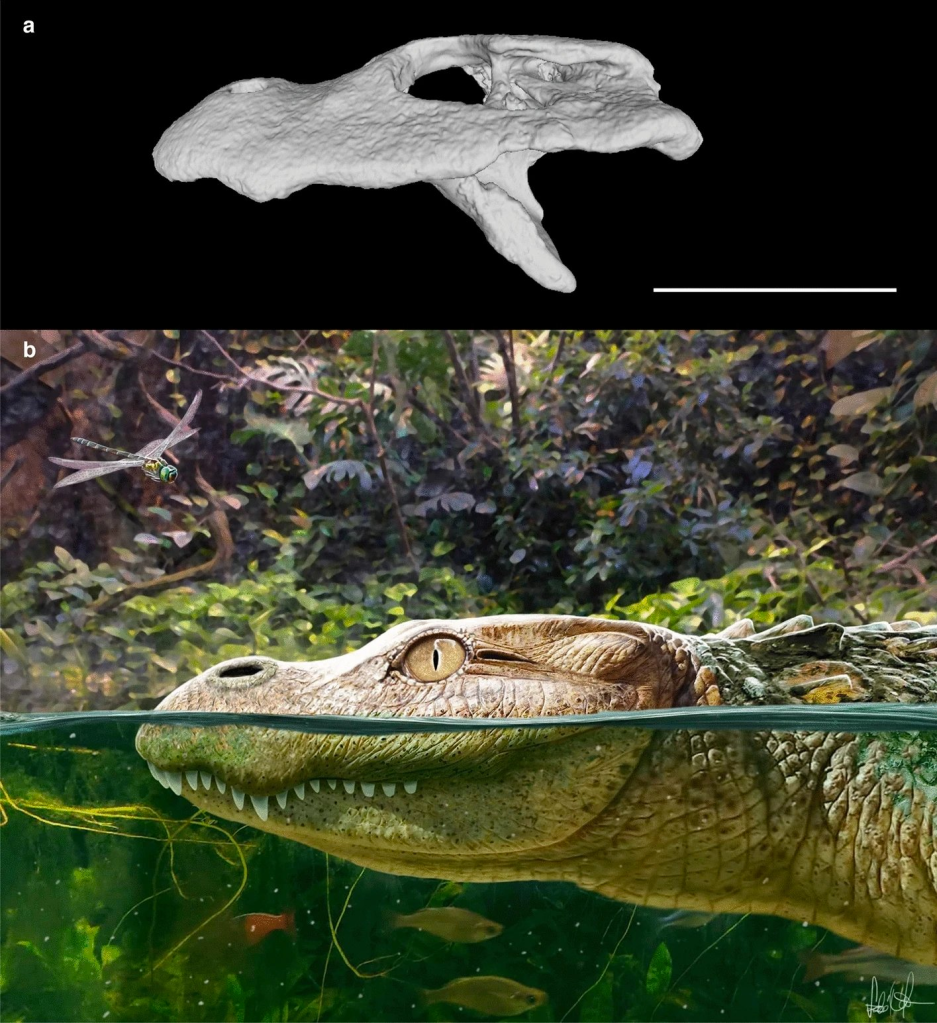

In Thailand, the short-faced Alligator munensis was described from a new skull[vi]. While A. munensis was closely related to the living Chinese alligator, it had a crushing bite which resembled older alligators. The last new species is Mirusodens caii, a primitive gliding mammal from the Jurassic period of China. Mirusodens may be one the best-preserved mammals from the Mesozoic epoch, exhibiting traits like differentiated hairs and claw sheaths[vii]. While it would have been tempting to pet the small and fluffy Mirusodens, it may not have been in your best interest!

Parenting Pterosaurs?

Inferring behaviours from anatomy and physiology is difficult but not impossible. A recent analysis of pterosaur growth patterns indicates that larger pterosaurs, namely Pteranodon, were incapable of advanced flight early in life and would have thus relied on parental support[viii]. Conversely, smaller pterosaurs (like Rhamphorhynchus) were born with developed wings and could live independently directly after hatching. The authors conclude that the increased parental behaviours may have resulted in the gigantism exhibited by later pterosaurs, allowing species like the 7-meter Pteranodon to flourish. Given the rarity of pterosaur eggs and nests, this study could prove crucial to understanding how these reptiles became the largest animals to ever take to the skies.

Creepy Crawlies Around the Globe:

If insects creep you out, I suggest you skip this section. In a series of fossils reminiscent of Jurassic Park, multiple centipedes have been discovered in European amber[ix]. While we can’t use these centipedes to clone dinosaurs, they provide an intimate glimpse into the fauna of our world during the Eocene greenhouse.

The second of our creepy crawlies comes from western Germany in the form of a fossilized spider. Named Arthrolycosa, this stunning specimen hails from the Carboniferous period (315-310 million years ago), making it one of the oldest spiders in the fossil record[x]. Despite other insects growing to gigantic sizes during the Carboniferous, spiders were newcomers and relatively rare. Hear that, arachnophobes? If you can stand 2-meter millipedes and eagle-sized dragonflies, the Carboniferous was the place for you!

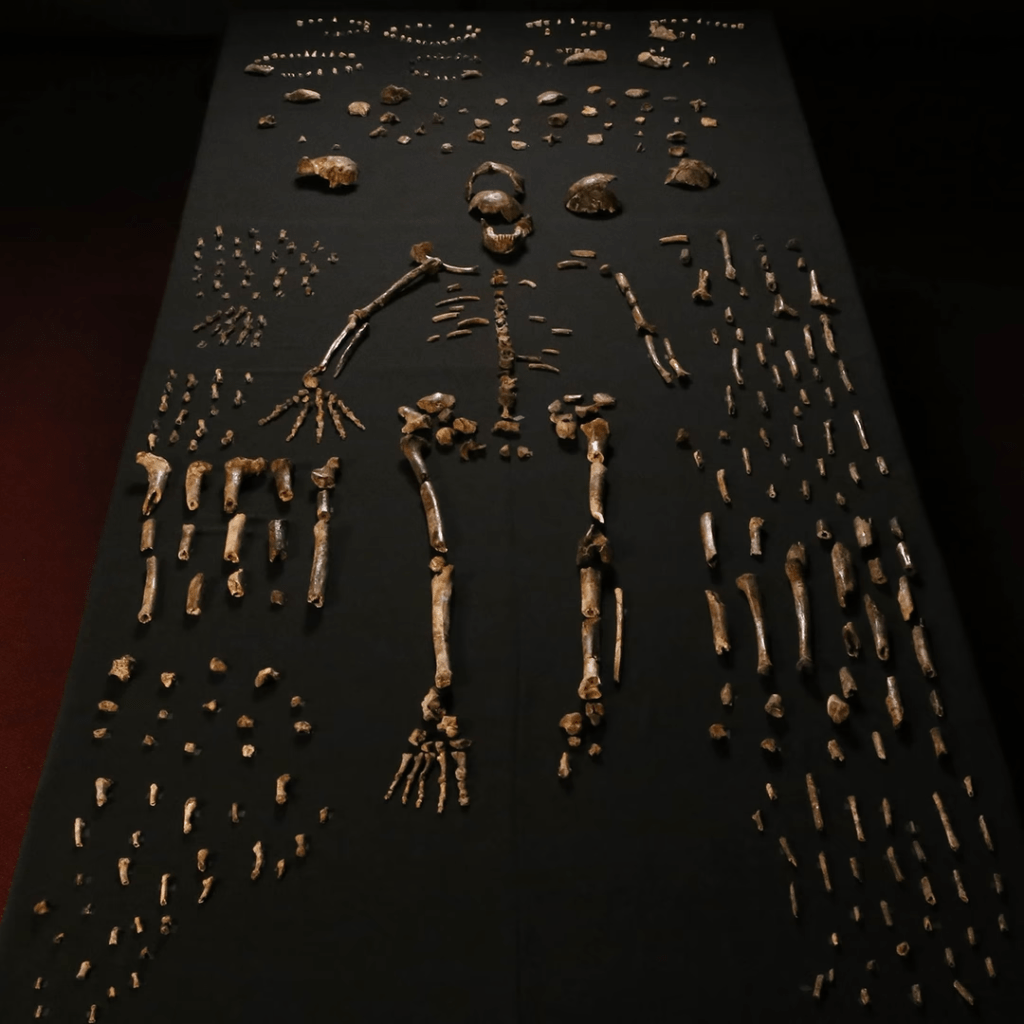

Cave of Bones: The Newest Controversial Documentary

Did ancient human relatives bury their dead? That is the question raised by Unknown: Cave of Bones, Netflix’s newest documentary about fossils of the early Homo genus Homo naledi from the Rising Star cave system in South Africa. While the film’s scientists argue that the fossils of Rising Star prove that humans with brains one-third our size practised advanced social and cultural behaviours before Homo sapiens did, doubt has been raised as to the validity of their claims. Regardless, Cave of Bones is a fascinating story of discovery, deduction, and paleoanthropology that attempts to shed light on the history of early humans.

Digging Out East: Maryland’s Newest Fossil Site

Dinosaur fossils from eastern North America are rare, so the discovery of a bonebed in Maryland, USA, is incredible. Dating to the early Cretaceous period 115 million years ago, the bonebed was discovered in 2014 in a Maryland Dinosaur Park just south of Baltimore[xi]. The bonebed is extensive and contains remains of a large theropod, possibly the sailed-back Acrocanthosaurus; the armoured ankylosaur Priconodon; an ornithomimid; a raptor (Deinonychus?); a new species of sauropod; a tooth from an early Tyrannosaur, which would be amongst the oldest found in North America; crocodile teeth; and a stingray. All things considered, the new site has produced quite the haul!

Ground Sloths & I: What can Their Remains Tell us About Humanity?

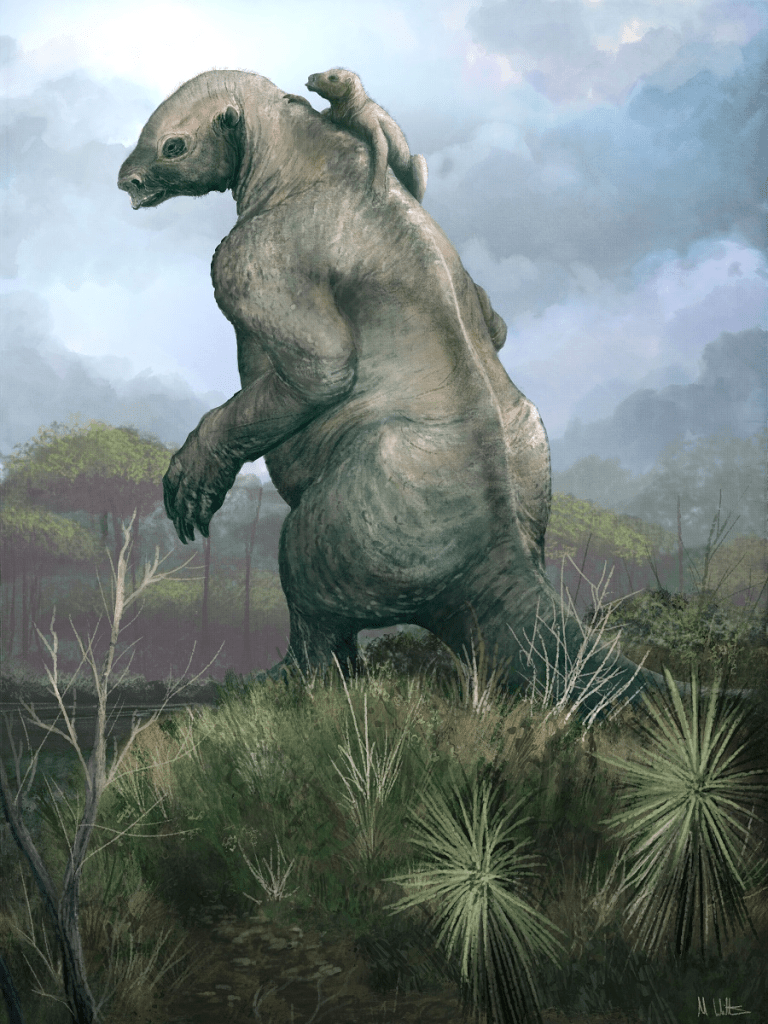

The month of paleontological advancement ends in Brazil, where two new studies related to giant ground sloths have uncovered quite different information. In the Toca da Boa Vista cave, a pregnant Nothrotherium was discovered alongside a late-stage, well-preserved fetus[xii]. The fetus is large (~1/3 the length of its mother) and was the only baby preserved, indicating that giant sloths gave birth to one baby like their modern ancestors. One interesting detail is that the long forearms of the fetus have been linked to climbing up its mother’s back after birth, which was predicted by paleoartist Mark Witton several years ago:

The second study features a series of ground sloth armour plates – known as osteoderms – carved by ancient humans in another Brazilian cave[xiii]. Not only is this discovery a fascinating glimpse of ecological interaction between ground sloths and our ancient ancestors, but it also pushes back the timeline of humans in the Americas. The carved bones date between 27,000-25,000 years ago, making them some of the oldest artifacts left by humans in South America. While past studies believed humans first migrated to the Americas ~15,000 years ago, the discovery of carved ground sloth bones is part of a growing list of evidence that indicates their migration occurred much earlier. Who would have thought that the key to understanding human migration would lie in the bones of a giant sloth!

Thank you for reading today’s article! Let’s hope that the rest of 2023 turns out to be just as productive for paleontology as July was! As per usual, I do not take credit for any images found in this article. The header image comes courtesy of Andrey Atuchin, Edgecombe et al., Gang Han, and Thais Rabito Pansani/AP

Works Cited

[i] Manitkoon, Sita, et al. “A New Basal Neornithischian Dinosaur from the Phu Kradung Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Northeastern Thailand.” Diversity, vol. 15, no. 7, 2023, p. 851, https://doi.org/10.3390/d15070851.

[ii] Gorscak, Eric, et al. “A New Titanosaurian (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Quseir Formation of the Kharga Oasis, Egypt.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2199810.

[iii] Ishikawa, Hiroki, et al. “Furcatoceratops Elucidans, a New Centrosaurine (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the Upper Campanian Judith River Formation, Montana, USA.” Cretaceous Research, 2023, p. 105660, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105660.

[iv] Jiangzuo, Qigao, et al. “Langebaanweg’s Sabertooth Guild Reveals an African Pliocene Evolutionary Hotspot for Sabertooths (Carnivora; Felidae).” iScience, 2023, p. 107212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107212.

[v] “New Archosaur Species Shows That Precursor of Dinosaurs and Pterosaurs Was Armored.” ScienceDaily, 26 July 2023, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/07/230726113005.htm.

[vi] Darlim, Gustavo, et al. “An Extinct Deep-Snouted Alligator Species from the Quaternary of Thailand and Comments on the Evolution of Crushing Dentition in Alligatorids.” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36559-6.

[vii] Mao, Fangyuan, et al. “A New Euharamiyidan, Mirusodens Caii (Mammalia: Euharamiyida), from the Jurassic Yanliao Biota and Evolution of Allotherian Mammals.” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad050.

[viii] Yang, Zixiao, et al. “Allometric Wing Growth Links Parental Care to Pterosaur Giantism.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 290, no. 2003, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.1102.

[ix] Edgecombe, Gregory D., et al. “An Eocene Fossil Plutoniumid Centipede: A New Species of Theatops from Baltic Amber (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha).” Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, vol. 21, no. 1, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2023.2228796.

[x] Dunlop, Jason A. “The First Palaeozoic Spider (Arachnida: Araneae) from Germany.” PalZ, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-023-00657-7.

[xi] Carballo, Rebecca. “Rare Dinosaur ‘bonebed’ Is Discovered in a Maryland Park.” The New York Times, 15 July 2023, http://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/15/us/dinosaur-fossils-maryland.html.

[xii] Pujos, François, et al. “Description of a Fetal Skeleton of the Extinct Sloth Nothrotherium Maquinense (Xenarthra, Folivora): Ontogenetic and Palaeoecological Interpretations.” Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-023-09665-5.

[xiii] Pansani, Thais R., et al. “Evidence of Artefacts Made of Giant Sloth Bones in Central Brazil around the Last Glacial Maximum.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 290, no. 2002, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.0316.

6 replies on “Ferocious Mammals, New Dinosaurs, and Sliced up Ground Sloths: July 2023 in Paleontology”

Thanks Max for the info….l am a 70yo who has always been fascinated by these wonderful creatures and l now look forward to your blogs…l would love to know what you think was and is still the cause that created a change…re eyes to evolve.. cartridge to bone….a horn, a fin, a tooth, a scale etc. I understand it took millions of years….even a the variety of bird’s beeks governed by their diet….what might it be that alters the blueprint ever so slowly? Robert from Victoria Australia

LikeLike

Hey Robert! Generally speaking, random mutations in the genomes of all living things are responsible for the alterations and adaptations we witness in nature. That’s not to say evolution is a random process, however. In order for these mutations (such as the ones responsible for eyes, teeth, etc.) to catch on and proliferate, they must be passed down through generations, meaning the individuals who experience such mutations must be successful enough to live for extended periods of time and mate with others of their own species. In general, change in species and lineages are dictated by whether an adaptation increases either the survival of an individual or the success an individual has in reproduction.

LikeLike

Is this inspired by my idea?

LikeLike

Nope! Just been a crazy month I thought was worth an article dedicated to it!

LikeLike

https://photos.app.goo.gl/K54t5x2J19mUQY7k7

This is from a seamount in the Mohave desert. Please respond to this message.

I have not had any luck getting anyone to look and appreciate the opportunity that this site provides.

LikeLike

The rock in the photo appears to be a form of Jasper, which is known to be common in Mojave. I’m not sure if it has any fossils present, but I would suggest trying the Fossil ID community on Reddit for a better analysis. They are generally able to answer quickly and thoroughly!

LikeLike