If you’ve been following this website for some time, you may have noticed that I have a certain fascination with prehistoric mummies. From baby Mammoths to armoured dinosaurs set adrift, there’s something visceral about getting the chance to look upon a long-extinct animal as though they were still alive. It’s hard to pinpoint where this obsession originated from, but in any case, the beauty and ultimate tragedy of prehistoric mummies will always pique my interest.

Given this, you can imagine my excitement when news of a saber-tooth cat mummy found in Siberian permafrost broke the brains of every paleonerd the world over:

Meet the discovery of the year, folks!

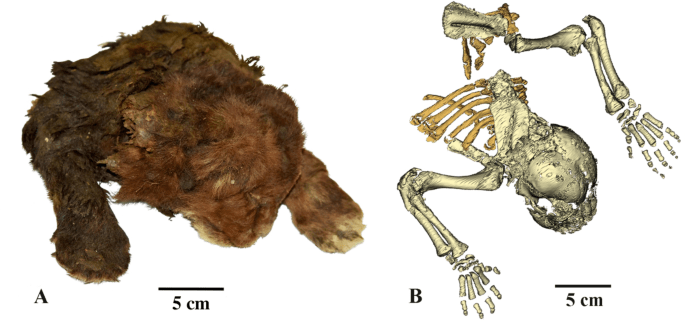

On November 14th, paleontologists led by Alexey Lopatin published their description of a baby big cat (only three weeks old) discovered in Siberian permafrost[i]. While mummified fauna from the Pleistocene Epoch are routinely discovered in northeast Russia, the strange features of the small cub caught the eyes of the team describing it. The thick and long neck, near-rounded front paws, and unique shape of the ears, muzzle, and braincase all set the cub apart from lion cubs of a similar age, signaling that the specimen represents something special.

Using the internal anatomy of the skull and mandible, the team has proposed a match for the cub’s identity: Homotherium latidens. Known colloquially as the ‘scimitar-toothed cat’, Homotherium was one of the largest and last members of the big cat family Machairodontinae, a group which includes Smilodon and several other sabre-toothed felids. While the canines of Homotherium weren’t as impressive as those possessed by their more famous relative, they still would have packed quite the punch, turning Homotherium into one of the top predators of the Pleistocene.

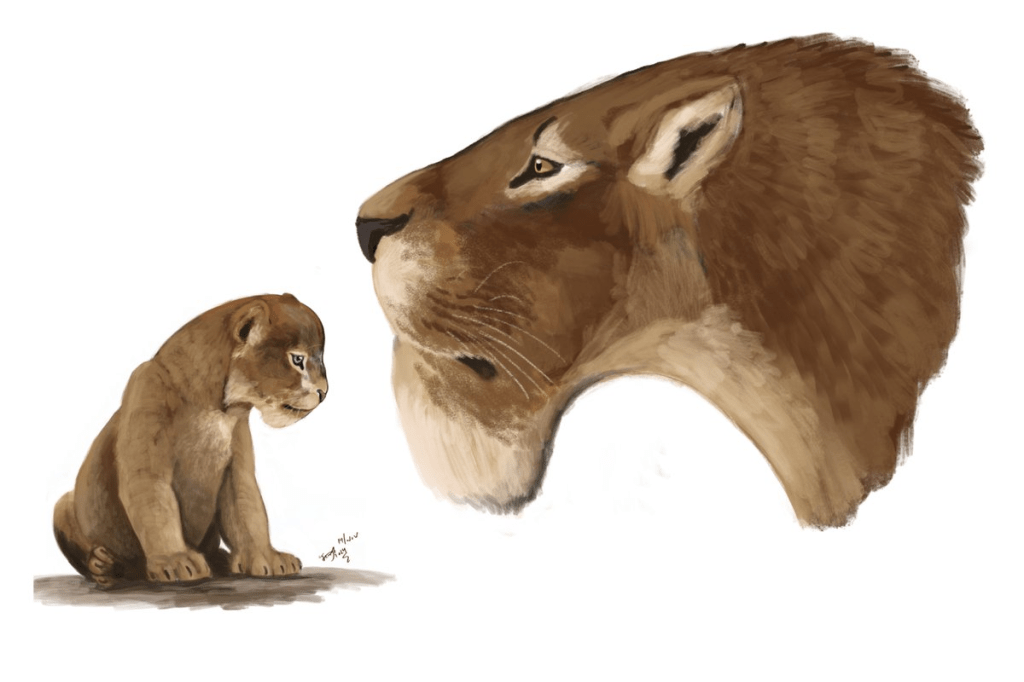

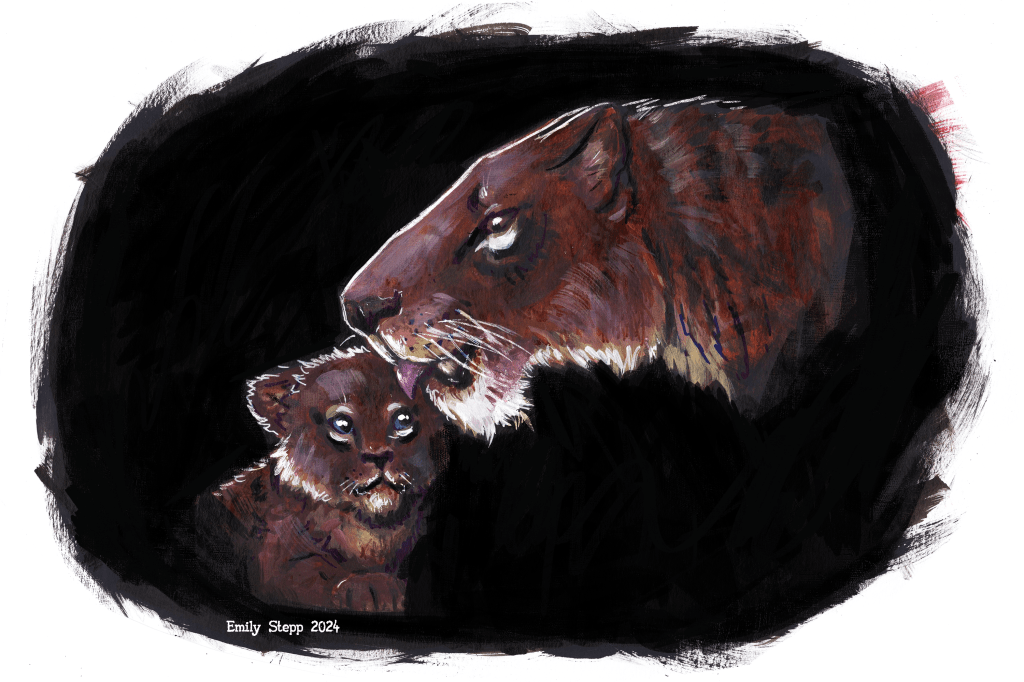

The identification of the mummy as Homotherium has provided paleontologists their first glimpse at the life appearance of saber-tooth cats. While it is important to remember that the colours and patterns of big cat fur can change over time, plenty of valuable information can still be learned from the cub. The fur is primarily short and a rich brown colour, though a noticeable patch of longer, blond hair is present on the chin. Paleoartists have run wild with this tuft, with some depictions featuring large beards on adult individuals:

What I am most fascinated with is the massive neck of the cub, described as “longer and twice as thick” than the lion cubs compared in the study. It has long been hypothesized that saber-tooth cats were more physically powerful than modern pantherines[ii], thus allowing them to subdue larger prey. The presence of a large, muscular neck in a young cub adds support to this theory, highlighting some of the differences between the saber-tooth cats and their extant cousins.

On the topic of differences, the paws of the Homotherium cub seem to be well adapted for life on the tundra. The paws are near-circular and lack carpal pads, a small area of fatty tissue that helps cats with movement stability and bracing impacts from jumping and climbing[iii]. This contrasts the paws observed in the lion cub, which are much longer and possess the carpal pad common to all living cats. While I am not sure what this absence would have meant for Homotherium, I can say the wide paws would have made for excellent snowshoes, allowing Homotherium to track and pursue prey in the thick snows of Siberia.

The last interesting trait of the cub is the skin on the muzzle and how it relates to Homotherium’s sabers. In recent years, many paleontologists have theorized that the massive canines of the Machairodontines were covered by skin from their upper lip, with brilliant paleoartist Mauricio Antón publishing a study about this theory in 2022[iv]. Though some have scoffed at this notion, the baby Homotherium appears to have a lip more than double the size of the lion, providing support to the sheathed-saber theory.

While I’m sure there is a certain crowd that may recoil at this notion, it makes sense that saber-tooths like Homotherium would want to protect their deadly weapons. After all, it’s not like samurai or knights always kept their swords drawn!

The last important thing to note is the reported age of the specimen. Using radiocarbon dating, Lopatin et al. estimate that the cub is approximately 32,000 years old. Paleontologists had long believed that Homotherium went extinct in Eurasia around 300,000 years ago, with only populations living in North America surviving until the end of the Pleistocene, approximately 12,000 years ago[v]. While a 2017 study proposed that a ~28,000-year-old jawbone discovered in the North Sea belonged to a surviving Homotherium, some doubts persisted[vi]. Yet the presence of a 32,000-year-old cub in Siberia dispels these notions, confirming that Homotherium was present in Eurasia during the latest Pleistocene.

There is evidence to suggest that the Eurasian Homotherium at the end-Pleistocene was a different species than their older counterparts, however. DNA from both the North Sea and mummified specimens place the individuals as H. serum, the North American species of Homotherium, and not H. latidens, the species present in Europe during the earlier stages of the Pleistocene. While Lopatin’s paper confusingly states that the name latidens should take priority for the cub, what appears to have happened is that H. latidens did go extinct in Eurasia, only for H. serum to return from North America over 250,000 years later. In this case, the cub would not represent H. latidens, rather a H. serum whose family were part of a late Eurasian colonization.

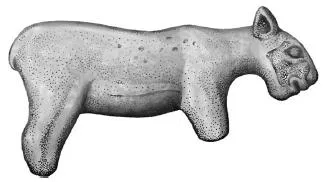

The confirmation of Homotherium in Late Pleistocene Eurasia does raise an important question: did they interact with Homo sapiens? The answer is almost certainly yes, and archaeological evidence may exist to support this interaction. In the French cave Isturitz, a site occupied by ancient humans during the Pleistocene approximately 30,000 years ago, archaeologists discovered a statuette of a big cat unlike any alive today[vii]. While the statue was believed to represent a Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea, due to the extirpation of Homotherium in Eurasia at the time of crafting, the confirmed presence of Homotherium should raise questions about its identity.

It may very well be a cave lion, but until further examination is undertaken, I would hesitate to give it a label. We do have mummies of Cave Lion cubs too; perhaps a comparison of the two may be in order?

It’s hard to properly say how awesome this discovery is. For years, paleontologists (including myself) have pondered what a saber-tooth cat would look like in life; would it have spots? Stripes? Manes like a lion? Now, we have our answer in the form of perhaps the cutest mummy ever discovered. While the circumstances behind its preservation were certainly tragic, the bearded cub has finally brought us face-to-face with a relic of a recent past.

Now, all the little cub needs is a proper name. All the other mummies have one, after all; what’s stopping this one?

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the respective artists, with the header coming courtesy of Lopatin et al., 2024.

Works Cited:

[i] Lopatin, A. V., Sotnikova, M. V., Klimovsky, A. I., Lavrov, A. V., Protopopov, A. V., Gimranov, D. O., & Parkhomchuk, E. V. (2024). Mummy of a juvenile sabre-toothed cat Homotherium latidens from the Upper Pleistocene of Siberia. Scientific Reports, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79546-1

[ii] Salesa, M. J., Antón, M., Turner, A., & Morales, J. (2009). Functional anatomy of the forelimb in Promegantereon* ogygia (Felidae, Machairodontinae, Smilodontini) from the Late Miocene of Spain and the origins of the sabre‐toothed felid model. Journal of Anatomy, 216(3), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01178.x

[iii] Rogers, C. D. (2024, September 25). Cat Paw Pads: Vet-Verified Anatomy & Functions Explained (With Diagram). Catster. https://www.catster.com/lifestyle/cat-paw-pads-anatomy/

[iv] Antón, M., Siliceo, G., Pastor, J. F., & Salesa, M. J. (2022). Concealed weapons: A revised reconstruction of the facial anatomy and life appearance of the sabre-toothed cat Homotherium latidens (Felidae, Machairodontinae). Quaternary Science Reviews, 284, 107471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107471

[v] Lallensack, R. (2017). Sabre-toothed cats prowled Europe 200,000 years after supposedly going extinct. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2017.22861

[vi] Paijmans, J. L., Barnett, R., Gilbert, M. T. P., Zepeda-Mendoza, M. L., Reumer, J. W., De Vos, J., Zazula, G., Nagel, D., Baryshnikov, G. F., Leonard, J. A., Rohland, N., Westbury, M. V., Barlow, A., & Hofreiter, M. (2017). Evolutionary History of Saber-Toothed Cats Based on Ancient Mitogenomics. Current Biology, 27(21), 3330-3336.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.033

[vii] Naish, D. (n.d.). Darren Naish: Tetrapod Zoology: The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats. https://darrennaish.blogspot.com/2006/03/late-survival-of-homotherium-confirmed.html

3 replies on “Saber in the Snow: A Mummified Homotherium Cub from Siberia”

That’s an amazing discovery! Interesting article, many thanks.

LikeLike

[…] strong prey like Ibex, Sheep, and Tahr. One thing is for sure: between the Cave Lions, Lynxes, Homotherium, and now Snow Leopards, Pleistocene Europe would have been teaming with big […]

LikeLike

It’s worth noting that Homotherium is often interpreted as being unusually cursorial as cats go (in fact, it might have been the only cat to be a proper endurance hunter rather than an ambush hunter), which might explain the differences in the paw anatomy.

LikeLike