The witching hour is upon us, folks: Nanotyrannus is recognized as a valid genus, and one that is stranger than initially believed.

Rise, Nanotyrannus! RISE!

On October 30th, the preliminary results of a research effort led by Drs. Lindsay Zanno and James Napoli of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (NCSM) were revealed to the public. Soon to be published in Nature, their study describes one component of the “Dueling Dinosaurs,” a tremendous specimen from Montana that contains an adult Triceratops and a smaller tyrannosaurid that appear to be locked in combat. After undergoing several highly publicized legal disputes for over a decade, the Dueling Dinosaurs finally found a home at the NCSM in 2020, enabling comprehensive research on the specimen.

Their study – which describes the tyrannosaurid fossils present in the Dueling Dinosaurs – is incredible. The specimen, NCSM 40000, is perhaps the most complete tyrannosaurid ever discovered, with every single bone accounted for[i]. It’s hard to contextualize how rare that level of completion is, but let’s just say it might just be the paleontological equivalent of winning the lottery! The completion and amazing condition of the skeleton has afforded Drs. Zanno and Napoli a brilliant chance to settle one of the most longstanding debates in dinosaur paleontology: is the “pygmy” tyrannosaur Nanotyrannus a valid genus?

The controversial history of Nanotyrannus lancensis has been discussed on this website at length, but it’s still important to catch folks up. In 1988, paleontologists Robert Bakker, Phil Currie, and Michael Williams described a new genus of tyrannosaur, Nanotyrannus, based on a skull housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CMNH 7541)[ii]. This discovery was significant, revealing that a much smaller tyrannosaur lived alongside its more infamous cousin, Tyrannosaurus rex, in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana during the late Cretaceous. The discovery of a second specimen housed at the Burpee Museum of Natural History, nicknamed “Jane,” added further fuel to the raging fires of Nanotyrannus’ status as the second Hell Creek tyrant.

Not all paleontologists were convinced. Analyses first conducted in 1999 by Thomas Carr and later by additional paleontologists found that CMNH 7541 and Jane were juveniles[iii][iv]. These studies, coupled with detailed research on the growth stages of the Asian tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus bataar, suggested that Nanotyrannus was not a distinct taxon, but rather represented immature individuals of Tyrannosaurus rex[v]. Despite numerous attempts to challenge these results, the consensus always shifted towards the juvenile Rex hypothesis, largely because a mature Nanotyrannus hadn’t been found. Without this smoking gun, the validity of Nanotyrannus was a long shot.

The funny thing about smoking guns? They do exist – sometimes it just takes 38 years to find them.

In their paper, Drs. Zanno and Napoli demonstrate that the Dueling Dinosaur specimen represents the first fully grown Nanotyrannus. Their first major piece of evidence supporting this discovery is in the anatomy of the specimen, which bears several key resemblances to established Nanotyrannus-morphs, including Jane and CMNH 7541. Once this connection was established, the presence of several anatomical characters distinct from Tyrannosaurus rex started to raise red flags.

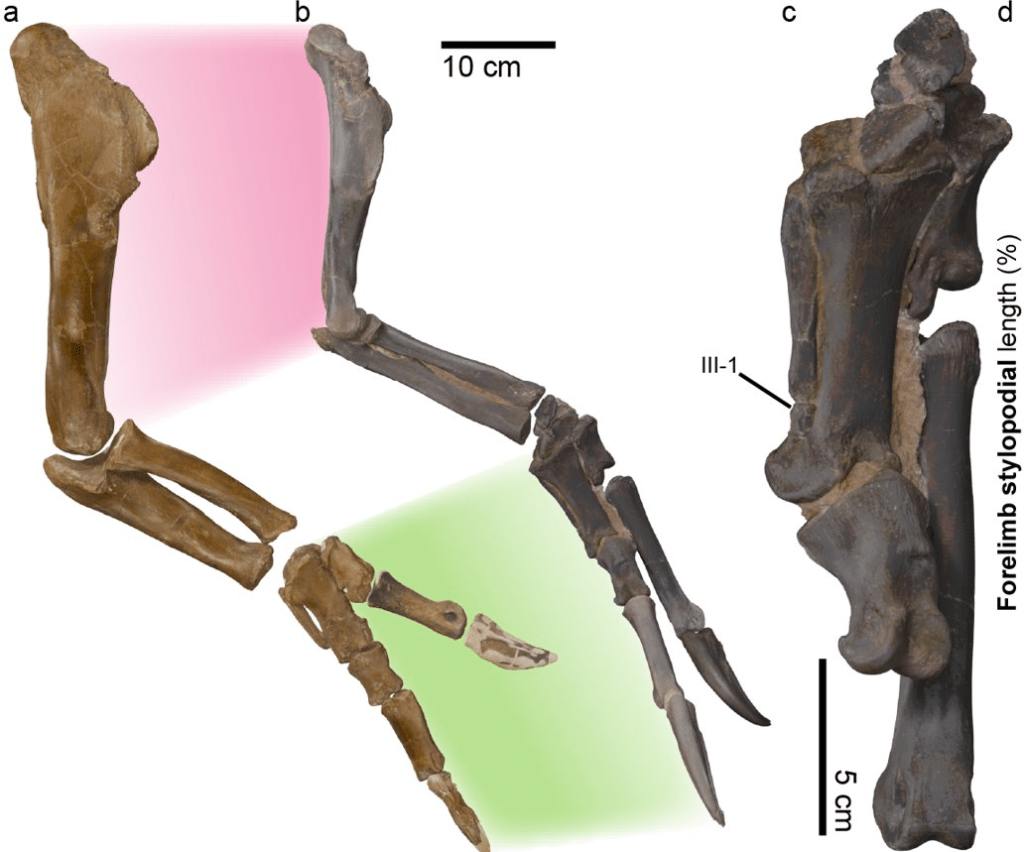

First, the bones of the hand more than double the length of known T. rex material. Second, the presence of a large sinus cavity on the quadratojugal of the skull is unlikely to have developed during ontogeny, thus makings its absence in T. rex a key difference. Third, the tooth count in the maxilla of Nanotyrannus specimens (between 15 and 17) is different compared to all T. rex specimens, which possess 12 or less. Tooth count has always been debated as an ontogenetically variable character in Tyrannosaurus rex, but the quadratojugal sinus is a bit more convincing. Fourth, the tail possessed fewer vertebrae than T. rex[vi]. Finally, many of the key diagnostic traits in T. rex – including skull width and length – are absent or altered in Nanotyrannus specimens.

Yet all these characters pale to the real smoking gun: the age of the specimen. To determine this, Drs. Zanno and Napoli performed bone histology on the specimen and found the final piece to the Nanotyrannus puzzle: NCSM 40000 was an adult, aged approximately 20 years old. After years of searching, we finally have the adult Nanotyrannus specimen that establishes the genus to be distinct from Tyrannosaurus rex. After all, it’s hard to call all Nanotyrannus specimens juvenile T. rex when one of them is an adult, right?

The study gets even more mind-blowing. After comparing NCSM 40000 to Jane, it was discovered that enough differences exist to crown a second species of Nanotyrannus, named N. lethaeus after the river of the underworld in Greek mythology. Given that Jane is immature and already larger than NCSM 40000, it is possible that N. lethaeus was a much larger species than N. lancensis. I’m hesitant about N. lethaeus truly representing a distinct species of Nanotyrannus, but for now, it seems as though two species of tiny tyrants roamed North America during the Late Cretaceous.

All this begs the question: what exactly was Nanotyrannus? Sure, it is a smaller tyrannosaur, but what kind of Late Cretaceous tyrant has a vestigial third finger? As it turns out, Drs. Zanno and Napoli’s phylogenetic analyses found Nanotyrannus to be an early diverging tyrannosaurid outside clade Tyrannosauridae, which includes most Late Cretaceous taxa. Instead, their analyses found two potential relationships. The first places Nanotyrannus as a close relative to the first Tyrannosauroids to migrate to North America, namely Moros intrepidus. This possibility raises several questions, namely the potential for a ghost lineage, as 25 million years separates Moros from Nanotyrannus.

The second possibility is much more plausible and intriguing: Nanotyrannus was an Appalachian tyrannosauroid. During much of the Cretaceous, North America was separated into two landmasses by a giant inland sea. Many of the tyrannosaurids you are familiar with, such as Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus, represent taxa present in the western landmass, Laramidia. The tyrannosaurids in the eastern landmass Appalachia, Dryptosaurus aquilunguis from New Jersey and Appalachiosaurus montgomeriensis from the American south, were different from their cousins, and are instead characterized by smaller sizes and comparatively longer arms. Sound familiar?

Currently, little is known about the Appalachian tyrants, largely because the poor preservation conditions in Eastern North America during the Late Cretaceous left few fossils behind. However, by the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous some 70 million years ago, the seaway dividing North America had retreated, allowing the Laramidian and Appalachian dinosaurs to crossover. This may have allowed Appalachian dinosaurs like Nanotyrannus to move east, thus putting it into contact with another recent migrant to the continent: its distant cousin, Tyrannosaurus rex. The smaller size of Nanotyrannus may have allowed it to live in the shadow of its rival, partitioning food resources in places like the Hell Creek Formation of Montana.

It should be noted that not enough is known about the Appalachian tyrannosauroids to confirm that Nanotyrannus represents a member of their family. Hopefully, new discoveries will help answer this question.

The work done by Drs. Zanno and Napoli provides a firm answer to the Nanotyrannus dilemma, reflecting the best-supported conclusion based on current evidence. Like Michael Myers stalking through the night, Nanotyrannus has returned with a vengeance!

Beyond the resurrection of an invalid taxon, this study has far greater consequences for our understanding of Tyrannosaurus rex. Nanotyrannus being distinct upends much of what we know about T. rex growth and development, since previous research assumed that Nanotyrannus specimens represented juveniles of the former genus. While this obviously introduces plenty of problems, it should be noted that young T. rex specimens still do exist, including the auctioned specimen “Chomper” and the recently discovered “Teen Rex” at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Time will tell whether these represent Nanotyrannus as well, but the early photos of Teen Rex look quite a bit different from known Nanotyrannus materials:

Another potential consequence of this discovery is how it affects tyrannosaur ontogenetic niche partitioning theory, which postures that the lack of mid-sized predators in places like the Hell Creek Formation can be explained by juvenile tyrants filling this niche. While support for this theory still exists (shoutout Gorgosaurus libratus[viii]), its mechanisms in the Hell Creek are now unclear due to the presence of Nanotyrannus. Did juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex fill a different ecological role than their parents, thus putting them in direct competition with Nanotyrannus? Or did they live and share a lifestyle with their parents, as has been observed in older tyrannosaurids[ix]? For now, the answer is unclear.

I suppose we’ll just have to wait!

Now, time to address the elephant in the room: how this study has been received by the paleontological community. Like many paleontologists, I have been skeptical of Nanotyrannus in the past. The last time I wrote about this topic, I called Nanotyrannus a “pipe dream,” though in my defence that was in response to a study that did not have conclusions nearly as convincing as the ones made today. In that article, I stated the following:

“For things to change, a new specimen must show a fully mature Nanotyrannus or a distinct juvenile Tyrannosaurus. Since neither fossil exists, analyzing studies like this in meticulous detail should be reserved until new evidence emerges.”

Well, new evidence has emerged, and so my opinion has changed. This is how science works; conclusions are made based on available evidence, and when new evidence is presented, you make new conclusions. This isn’t a situation where we need to question why most did not consider Nanotyrannus valid and fill out an apology form for the dinosaur. As tends to happen in paleontology, a new, incredible specimen has introduced a convincing argument to a debate that results in opinions changing.

If you need more convincing, just remember that Lindsay Zanno was a coauthor on one of the last major papers refuting Nanotyrannus as a valid genus. Opinions change with evidence, folks!

Tangent aside, it is quite exciting to see the resurrection of Nanotyrannus. The number of known tyrannosaurid species in the end-Cretaceous of North America has tripled today, with two representing a bizarre offshoot of the lineage. Many questions must be answered, but for now, enjoy how one of the most incredible specimens known to science has already changed our understanding of paleontology’s most famous family.

Welcome back Nanotyrannus! Happy Spooky Day!

I do not take credit for any images found in this article. All images come courtesy of the sources alongside each piece. Header Image courtesy of Anthony Hutchings

Works Cited:

[i] Napoli, J. [@JGN_Paleo]. (2025, October 20). It’s real. And it’s spectacular. Sometimes, one fossil really can change everything you think you know. NEW PAPER (see bottom of thread) AND. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://x.com/JGN_Paleo/status/1983927494026854525

[ii] Bakker, R. T., Williams, M., & Currie, P. J. (1988). Nanotyrannus, a new genus of pygmy tyrannosaur, from the latest Cretaceous of Montana. Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1037529

[iii] Carr, T. D. (1999). Craniofacial ontogeny in Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(3), 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1999.10011161

[iv] Woodward, H. N., Tremaine, K., Williams, S. A., Zanno, L. E., Horner, J. R., & Myhrvold, N. (2020). Growing up Tyrannosaurus rex : Osteohistology refutes the pygmy “ Nanotyrannus ” and supports ontogenetic niche partitioning in juvenile Tyrannosaurus. Science Advances, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax6250

[v] Carr, T. D. (1999). Craniofacial ontogeny in Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(3), 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1999.10011161

[vi] The Case of the Tiny Tyrannosaurus Might Have Been Cracked – The New York Times

[vii] Brusatte, S. L., Benson, R. B. J., & Norell, M. A. (2011). The Anatomy ofDryptosaurus aquilunguis(Dinosauria: Theropoda) and a Review of Its Tyrannosauroid Affinities. American Museum Novitates, 3717(3717), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1206/3717.2

[viii] Therrien, F., Zelenitsky, D. K., Tanaka, K., Voris, J. T., Erickson, G. M., Currie, P. J., DeBuhr, C. L., & Kobayashi, Y. (2023). Exceptionally preserved stomach contents of a young tyrannosaurid reveal an ontogenetic dietary shift in an iconic extinct predator. Science Advances, 9(49). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adi0505

[ix] Titus, A. L., Knoll, K., Sertich, J. J., Yamamura, D., Suarez, C. A., Glasspool, I. J., Ginouves, J. E., Lukacic, A. K., & Roberts, E. M. (2021). Geology and taphonomy of a unique tyrannosaurid bonebed from the upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah: implications for tyrannosaurid gregariousness. PeerJ, 9, e11013. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11013

Zanno, L.E., Napoli, J.G. (2025). Nanotyrannus and Tyrannosaurus coexisted at the close of the Cretaceous. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09801-6