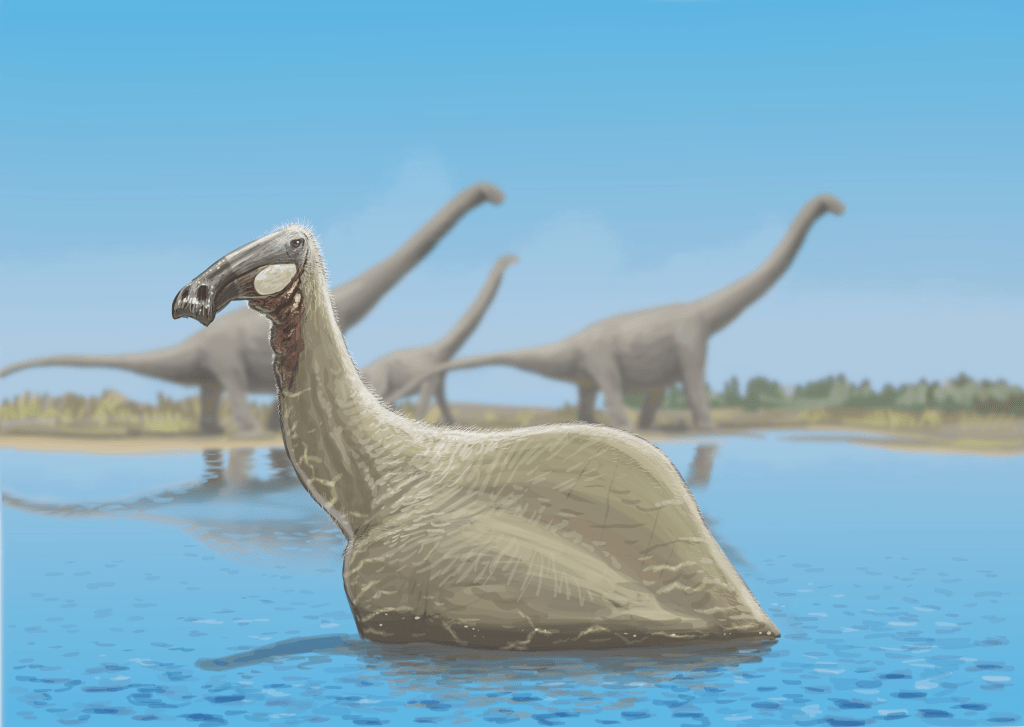

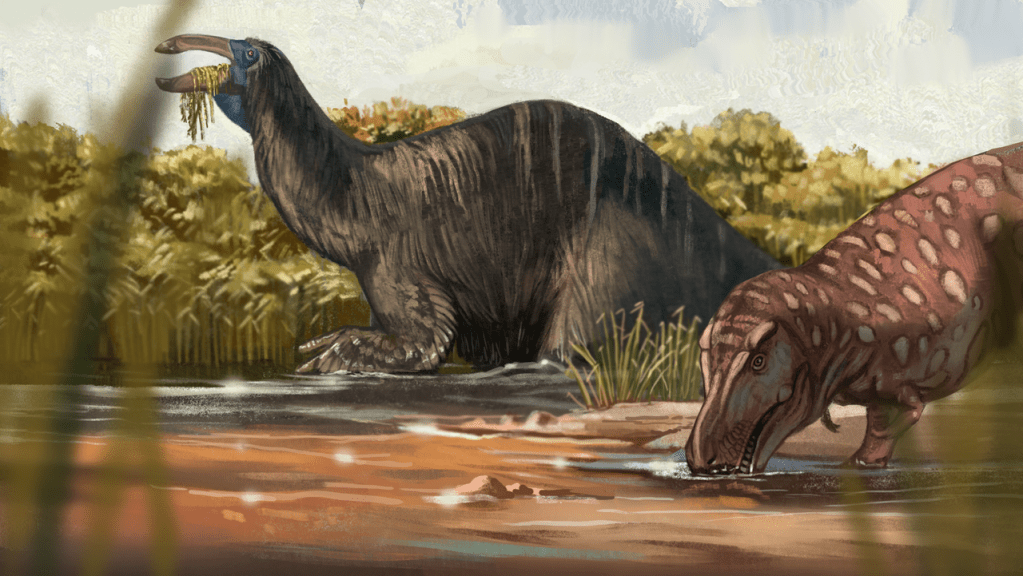

70 million years ago, in what is now Mongolia, a giant dinosaur waded through dense swampland. At 5 tonnes, this behemoth was amongst the largest animals on the continent, yet resembled none of the giant dinosaurs that came before it. At first glance, you might mistake this lumbering goliath for a massive duck, given its elongated face and feathers across its body. Yet the animal’s giant, sweeping arms and back hump give away its true identity: Meet Deinocheirus, one of the strangest dinosaurs known to science.

The most impressive arms you’ve ever seen!

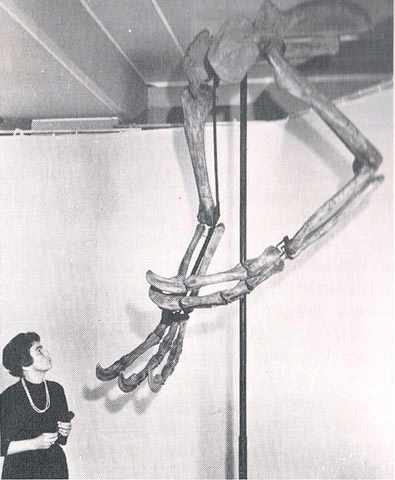

While the appearance of Deinocheirus is now apparent to paleontologists, it didn’t start that way. In the early 1960s, Polish paleontologists Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, Halszka Osmólska, and Teresa Maryańska embarked on a series of trips to the Gobi Desert of Mongolia in hopes of finding dinosaurs. The so-called Polish-Mongolian expeditions have become the stuff of paleontological legend, uncovering hundreds of fossils that comprised numerous new dinosaur species (such as Gallimimus and Bagaceratops) and even more mammals between 1963 and 1971. In an often male-dominated field, the female-led expeditions left their mark on paleontology in a way few others have!

The magnum opus of the Polish-Mongolian expeditions came in July of 1965 when Kielan-Jaworowska discovered a titanic pair of arms in the Nemegt Basin. Even though most of the skeleton was missing, the whopping 2.4-meter-long limbs indicated that the team had found a new species[i]. Most large theropods, such as T. rex and Giganotosaurus, possessed comparatively tiny arms, making the giant arms of the mystery theropod a true enigma. Because of their size, Osmólska named the creature Deinocheirus (Die-no-ky-rus) in 1970, which translates to “terrible hands.” Talk about fitting!

Unfortunately for paleontologists, the lack of a complete skeleton raised many questions about Deinocheirus. Osmólska recognized similarities between Deinocheirus and the long-legged Ornithomimosaurs; however, the incomplete nature of the specimen prevented Osmólska from making a definitive diagnosis[ii]. Even the massive arms came with a plethora of questions. Were they for hunting prey? For defence? What did the animal who possessed them look like? For almost 40 years, the answer to these questions remained unanswered, allowing the imagination of paleontologists to run wild with speculation.

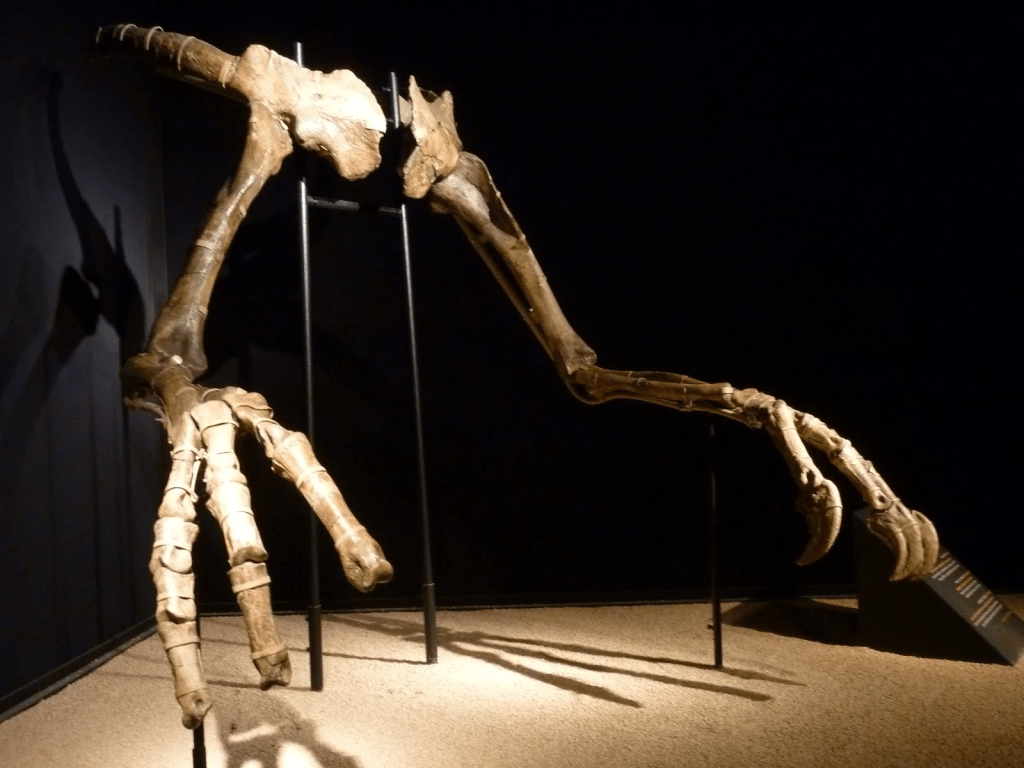

The terrible hands of Deinocheirus. ©Dinopedia

The picture forms…

It wouldn’t be until 2008 that more fossils of Deinocheirus emerged. In a joint expedition with crews from Mongolia and Korea, Canadian paleontologist Phil Currie set about rediscovering the original Deinocheirus fossil site with hopes of finding more remains. It wasn’t Currie’s first rodeo finding lost fossil sites; a decade prior, Currie rediscovered an Albertosaurus bonebed in southern Alberta lost for almost a century[iii]. If anyone could locate the Deinocheirus remains in the barren sands of the Gobi, it was Currie!

The expedition was a success. Using photographs of the site and hand-drawn maps from decades prior, Currie and the team located the site and additional remains of Deinocheirus, namely hundreds of rib fragments from the animal’s gastralia (abdominal ribs which aided dinosaurs in breathing)[iv]. While the rediscovery was a step in the right direction, plenty of mystery still surrounded Deinocheirus.

Then, in 2009, Currie and the Korean-Mongolian team made a breakthrough. Using a set of notes written on Mongolian currency by fossil poachers, Currie and the team were able to locate a new specimen of Deinocheirus at a location called Bugiin Tsav. While the poachers had taken elements of the animal’s skull, hands, and feet, the team recovered most of the animal’s remaining skeleton, including parts of the arm that confirmed it to be Deinocheirus. Additionally, their discovery allowed paleontologists to recognize that another specimen from the Nemegt – discovered in 2006 and identified as a Therizinosaurid – was Deinocheirus too!

Despite the plethora of new information, one crucial element was still missing: its head. Luckily for paleontologists, this wouldn’t remain the case for long. In 2011, halfway around the world, Belgian paleontologist Pascal Godefroit was notified about a strange specimen in possession of a German collector. Upon visiting, Godefroit recalled Currie’s efforts in Mongolia and contacted him to investigate the unique fossil. What Currie found was incredible: not only was the skull of Deinocheirus sitting right in front of him, but it also came from the same individual discovered in Bugiin Tsav two years prior!

How did Currie know for sure? First, Currie located a missing toe bone in the German collection downhill from the Bugiin Tsav site. Second, the two teams had bones from the hand of the specimen that fit together perfectly! After over 40 years of mystery, the true nature of Deinocheirus was almost ready to be revealed due to the detective skills of Currie and the Korean-Mongolian expedition and some good old-fashion luck!

Not your average Ornithomimosaur…

When Currie presented his findings at the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology’s annual meeting in 2013, paleontologists were astounded. While the conference usually features bold and controversial research (last year’s headliners were venomous mosasaurs (more about that here!) and dome-headed dinosaurs acting like Kangaroos), Deinocheirus still managed to stun paleontologists in a way few others have[v]. As you’re about to find out, it was for good reason!

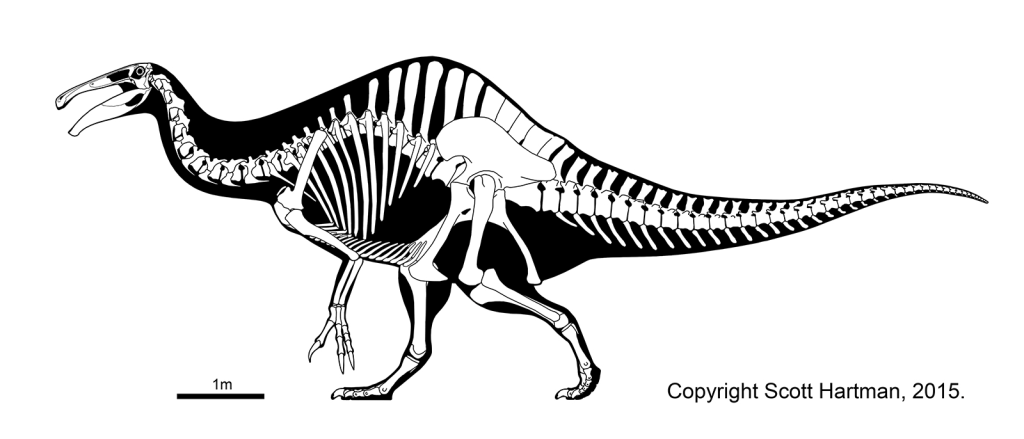

Let’s start with an essential question: What family did Deinocheirus belong to? While its giant arms may recall another large Mongolian theropod, the equally enigmatic Therizinosaurus, it turns out that Osmólska’s initial observations were correct: Deinocheirus was an Ornithomimosaur. Ornithomimosaurs, or “ostrich mimics,” are famously considered to be the Roadrunners of the dinosaurs. With long legs and a slender frame, Ornithomimosaurs could outpace the ferocious carnivorous dinosaurs they would have encountered during the late Cretaceous period with ease.

Yet Deinocheirus was nothing like its cousins. At 12 meters long and weighing somewhere between 5-7 tonnes, Deinocheirus outweighed its lightweight cousins by several thousand kilograms![vi] This was not an animal built for speed either; with short, compact legs, a broad pelvis, and splayed feet, the anatomy of Deinocheirus strongly suggests a plodding goliath. If you lined up Deinocheirus with other theropods and needed to identify its closest relatives, you would probably take several tries to land on the Ornithomimids!

The massive frame of Deinocheirus is far from its only quirk. Beginning at its dorsal vertebrae, the neural spines (the vertical portion of vertebrae) progressively increase in height to form an impressive sail[vii]. Instead of the thinner sail found in Spinosaurus, the sail of Deinocheirus was much thicker and proportioned lower on its body, which has led paleontologists to believe it supported the massive weight of Deinocheirus[viii]. While dinosaurs independently evolved sails on at least six (!!) occasions, Deinocheirus appears to be the only one to use its sail for balance and support. Why the others evolved sails is currently a point of contention, so if you have any theories, let me know!

Then there’s the skull. Measuring over a meter long, it is undoubtedly massive but is considerably narrow, toothless, and ends in a pseudo-beak. In other words, Deinocheirus did not attack large prey with it! Instead, the skull superficially resembles the herbivorous Hadrosaurids. However, these animals possessed thousands of teeth capable of grinding plant matter with unparalleled efficiency. Instead of chewing, the presence of over 1,400 stones (known as gastroliths) in the gut cavity of the Bugiin Tsav specimen indicates that Deinocheirus used gastroliths to digest their food like modern birds. But what was it eating?

The swamp monster?

The answer to this question might surprise you. Amongst the thousands of gastroliths were the remains of fish vertebrae and scales. The presence of fish bones in its stomach, alongside the spoonbill-shaped beak and gastroliths, has led paleontologists to speculate that Deinocheirus was an omnivore that lived in aquatic habitats. Apple TV’s docuseries Prehistoric Planet famously featured this hypothesis, where audiences follow a very shaggy Deinocheirus (more on that later) as it meanders through a prehistoric swamp:

More circumstantial evidence exists to support this hypothesis. Most paleontologists believe Ornithomimosaurs were omnivorous, which would have allowed Deinocheirus to exploit aquatic animals (including fish, clams, crabs, and more) and vegetation. The long arms of Deinocheirus lacked the claws to inflict real damage on contemporary dinosaurs, but could have aided Deinocheirus with scooping aquatic vegetation and fish into its massive mouth.

While this may be speculative, another piece of evidence could stem from the animals that lived alongside Deinocheirus. During the Late Cretaceous, the Nemegt Formation – the geological formation which all Deinocheirus fossils come from – was full of large herbivores. Amongst these were Barsboldia and Saurolophus, two large Hadrosaurids that were generalist browsers; at least two Ankylosaurids, armoured herbivores that specialized on low-lying leaves; Homalocephale and Prenocephale, small dome-headed herbivores; Nemegtosaurus, Opisthocoelicaudia and potentially more Sauropods, giant herbivores capable of clearing forests; and Therizinosaurus, another large tree browser. With so many herbivores, it would have made a lot of sense from an ecological standpoint for Deinocheirus to turn to the waterways and practise niche partitioning. If this is the case, Deinocheirus would have had plenty in common with Spinosaurus!

Fluffy giant?

One interesting question has arisen about Deinocheirus: Did it have feathers? Paleontologists know that other Ornithomimosaurs had feathers[ix], and the presence of a pygostyle – a plate of fused vertebrae at the end of the tail – suggests Deinocheirus did too[x]. Pygostyles are prevalent in modern birds, which use it as a base to support their tail feathers. Like the birds, Deinocheirus would have sported a set of feathers at the end of its tail, though the “tail fan” they formed were more for display than flight!

Whether it had feathers covering the rest of its body is far more controversial. From an evolutionary perspective, Deinocheirus having feathers was very plausible; however, from a physiological one, it was much more unlikely. Large animals have a lower surface area to volume ratio, meaning they have more difficulty expelling heat than smaller animals. A 5-tonne Deinocheirus would not have been exempt from this rule, meaning that an extensive covering of feathers theoretically would have caused it to overheat in the hot Mongolian climate. There’s a reason why most mammals that weigh more than a tonne are hairless, and the largest feathered animal in prehistory (the Tyrannosauroid Yutyrannus) only weighed 1 tonne.

If Deinocheirus did have feathers besides its tail, it would have likely been a thin coating. While Prehistoric Planet is a fantastic series, their depiction of Deinocheirus – while very humorous – is ultimately a bit unrealistic. (Prehistoric Planet criticism? In this website? That’s a first!). Despite this, the existence of tail feathers means that Deinocheirus is technically the largest feathered animal in Earth’s history (sorry, T. rex!). Quite the achievement if you ask me.

Kin of the dino-duck

In recent years, a handful of close Deinocheirus relatives – the Deinocheirids – have been described. In China, the half-tonne Ornithomimosaur Beishanlong is accepted as an early Deinocheirid, showing the beginnings of gigantism in the lineage. A few other potential Deinocheirids – the Chinese taxa Hexing and the Mongolian species Garudimimus and Harpymimus – have emerged, but their placement in Deinocheiridae is tentative.

More intriguing is the discovery of Deinocheirids in North America. First described in 2020, the 600kg Mexican species Paraxenisaurus represents the Deinocheirid’s foray into North America during the late Cretaceous[xi]. Paleontologists don’t know much about Paraxenisaurus, but its presence in North America highlights the vast faunal interchange between Asia and North America during the late Cretaceous, which brought dinosaurs like the Deinocheirids and even Tyrannosaurus rex to North America.

Recent discoveries have indicated that Paraxenisaurus wasn’t alone. In Mississippi, USA, a handful of tantalizing foot bones hint that a Deinocheirid the size of Deinocheirus roamed the American south, potentially dwarfing its Mexican cousin by several tonnes![xii] Like Paraxenisaurus, little is presently known about this genus, meaning that future research will be necessary to learn more. Regardless, the enigmatic Deinocheirids have far more left in store for paleontologists!

Life in paradise?

Life in the swamps of prehistoric Mongolia wasn’t completely peachy for Deinocheirus. Living alongside it was the Tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus, a 10-meter-long predator capable of hunting massive dinosaurs like Deinocheirus. The gastralia discovered at Bugiin Tsav preserved traces of Tarbosaurus bite marks, indicating that it preyed upon the giant omnivore[xiii]. Despite this, analysis of Tarbosaurus enamel suggests that it preferred Hadrosaurs and Sauropods, meaning that the predation of Deinocheirus appears to have been a one-off event[xiv]. Additionally, the bite marks appear to have occurred after the Deinocheirus died, highlighting the opportunism of big predators when it comes to free meals!

One of a kind…

To summarize, Deinocheirus was an elephant-sized dinosaur with the head of a duck, arms so large they would put Popeye to shame, a giant hump designed as a counterbalance for its massive weight, and a few feathers for extra excitement. While Max’s Blogosaurus has discussed plenty of weird dinosaurs – which you can read about here – Deinocheirus stands alone on the bizarreness scale. While mystery has long surrounded this enigmatic dinosaur, one thing remains clear: nothing will ever resemble it again!

Thank you for reading this article! Talking about bizarre dinosaurs is a staple of Max’s Blogosaurus folklore, and few dinosaurs compare to the Lovecraftian creation that is Deinocheirus. If mysterious theropods intrigue you, I’d suggest reading about Megaraptor and its kin here at Max’s Blogosaurus. At certain times, these giant predators have been considered raptors, Spinosaurids, Allosaurids, and one other lineage that will shock you!

I do not take credit for any image found in this article. The header image comes courtesy of the brilliant Dr. Mark Witton, whose work is on his website at the link below: https://www.markwitton.co.uk/

Works Cited:

[i] Pickrell, John. Weird Dinosaurs: The Strange New Fossils Challenging Everything We Thought We Knew. Columbia University Press, 2017.

[ii] Osmólska, Halszka, and Ewa Roniewicz. “Deinocheiridae, a New Family of Theropod Dinosaurs.” Palaeontologica Polonica, no. 21, 1970.

[iii] Currie, Phillip J. “Possible Evidence of Gregarious Behaviour in Tyrannosaurids.” Gaia, vol. 15, 1998, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7939/R3348GX03.

[iv] Bell, Phil R., et al. “Tyrannosaur feeding traces on deinocheirus (theropoda:?ornithomimosauria) remains from the Nemegt Formation (late cretaceous), Mongolia.” Cretaceous Research, vol. 37, 2012, pp. 186–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.018.

[v] Black, Riley. “Mystery Dinosaur Finally Gets a Body.” Culture, National Geographic, 3 May 2021, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/131104-dinosaur-hands-arms-body-mongolia.

[vi] Naish, Darren. Dinopedia: A Brief Compendium of Dinosaur Lore. Princeton University Press, 2021.

[vii] Lee, Yuong-Nam, et al. “Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus Mirificus.” Nature, vol. 515, no. 7526, 2014, pp. 257–260, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13874.

[viii] Yong, Ed. “Deinocheirus Exposed: Meet the Body behind the Terrible Hand.” Science, National Geographic, 3 May 2021, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/deinocheirus-exposed-meet-the-body-behind-the-terrible-hand.

[ix]Zelenitsky, Darla K., et al. “Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins.” Science, vol. 338, no. 6106, 2012, pp. 510–514, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1225376.

[x] Lee, Yuong-Nam, et al. “Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus Mirificus.” Nature, vol. 515, no. 7526, 2014, pp. 257–260, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13874.

[xi] Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés, et al. “Paraxenisaurus normalensis, a large deinocheirid ornithomimosaur from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (upper cretaceous), Coahuila, Mexico.” Journal of South American Earth Sciences, vol. 101, 2020, p. 102610, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102610.

[xii] Black, Riley. “Giant Ostrich-like Dinosaurs Once Roamed North America.” Smithsonian.Com, Smithsonian Institution, 19 Oct. 2022, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/giant-ostrich-like-dinosaurs-once-roamed-north-america-180980968/.

[xiii] Bell, Phil R., et al. “Tyrannosaur feeding traces on deinocheirus (theropoda:?ornithomimosauria) remains from the Nemegt Formation (late cretaceous), Mongolia.” Cretaceous Research, vol. 37, 2012, pp. 186–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.018.

[xiv] Owocki, Krzysztof, et al. “Diet preferences and climate inferred from oxygen and carbon isotopes of tooth enamel of Tarbosaurus Bataar (nemegt formation, Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia).” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, vol. 537, 2020, p. 109190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.05.012.

One reply on “Meet Deinocheirus, Mongolia’s Bizarre Dino-Duck”

[…] the subfamily of Ornithomimids which developed long arms best represented by genera like Deinocheirus and Paraxenisaurus. The presence of such-long arms has raised questions as to what Mexidracon was […]

LikeLike